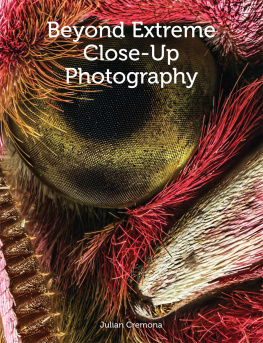

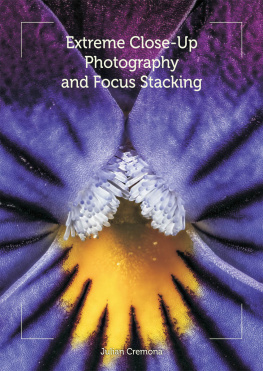

Beyond Extreme

Close-Up Photography

Beyond Extreme

Close-Up Photography

Julian Cremona

CROWOOD

First published in 2018 by

The Crowood Press Ltd

Ramsbury, Marlborough

Wiltshire SN8 2HR

www.crowood.com

This e-book first published in 2018

Julian Cremona 2018

All rights reserved. This e-book is copyright material and must not be copied, reproduced, transferred, distributed, leased, licensed or publicly performed or used in any way except as specifically permitted in writing by the publishers, as allowed under the terms and conditions under which it was purchased or as strictly permitted by applicable copyright law. Any unauthorised distribution or use of thistext may be a direct infringement of the authors and publishers rights, and those responsible may be liable in law accordingly.

British Library Cataloguing-in-Publication Data

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

ISBN 978 1 78500 466 7

Cover Photograph: Eye of the small elephant hawkmoth. Forty images have been focus stacked to create this composite image using Helicon Focus software. (6 magnification, Canon 7D mk2, 65mm MPE lens 5.6 ISO 100, with diffuse twin macro flash.) through several rinses in clean water to remove detritus.

Frontispiece: Part of the underside of a rose chafer beetle, Cetonia aurata. (7 magnification, Canon 7D mk2 with 65mm MPE, 32mm of extension tube, 5.6 ISO 100 twin macro flash, composite of thirty-two images.)

CONTENTS

Preface

The contribution of visible life to biodiversity is very small indeed.

Sean Nee writing in Nature, 2004.

I am a regular reader of the photographic press. The articles I enthusiastically lap up are as diverse as possible because this is one of my pet loves; taking photographs. My grandchildren know, just like their parents, that a camera will always be there to record the moment. Any moment of their lives. One, which some find strange, is the appearance and disappearance of teeth as they grow up; these can present technical challenges along with the personal level of dealing with my model. This should not come as a surprise to people who know me, because they realize that my passion is for anything natural and biological. The primary purpose of my travels around the globe is in the search for wilderness and then to record, through my photography, the life that exists there no matter what the size or type of organism. Learning through this form of research, I am better able to understand the dynamics of the natural world and go on to help in conservation and education.

Spanish scorpion photographed at night with black light (365nm wavelength), invisible to human eyes. In daylight the normal colour is yellow. Although this image is not an extreme close-up, it demonstrates that by photographing animals and plants in UV or infrared, some species become more striking and visible to us.

This leads me to a conundrum. I have met people who just photograph flowers (waiting for the insects to disappear first). There is the bird photographer: I was in a very small boat on a river in a remote part of Costa Rica with a guide. I was sharing this with a German photographer, tripod and very long lens at the ready. An exotic bird appeared and we both got snapping. A howler monkey in the tree above; crocodile up close baring its teeth in the water; a bright pink dragonfly at rest on the reed; only my camera was in action. The bird photographer would hardly look.

Now back to the photographic magazines.

I look at the wonderful wildlife photos. My interpretation of wildlife seems to be very different to others. Mammals like foxes, badgers, deer, elephants and tigers grace the pages along with birds and flowers. But surely flowers are not wildlife, are they? Or insects and sea anemones in a tide pool? Of course they are! I, and most biologists, fail to categorize creatures like the press because to me, all life that is wild should include all nature without exception. And here we reach the real ambiguity, because the vast majority of life on Earth is not visible to the naked eye. The photos we typically see in magazines, over and over, are just the tip of a huge biodiversity iceberg and 99.9 per cent of wildlife photographers are only taking photos of that tip. The enormity of what is left is largely overlooked.

Some people will discover more as they use a macro lens to take photos of butterflies and other insects (even macro is seen as a different genre to wildlife in many magazines). There are a host ofbooks and websites out there describing macro techniques, including extreme macro, but I am amazed that the sites are full of bees and flies. Where are the rest, such as beetle life in a pond or crabs on the seashore? There is so much more out there and still I am talking about the visible creatures, because almost all the biodiversity of life on our planet is not visible to our naked eye. Much of this has never been photographed and it will be in your garden, parkland or nearest wood or pond. Your range of subjects is vast and in practical terms inexhaustible.

The marine pseudoscorpion, Neobisium, photographed in 1998 with a Fuji bridge camera and an SLR lens reversed on to the front and coupled. (6 magnification, live specimen in seawater, natural light.)

Twenty years ago I photographed a tiny creature called a marine pseudoscorpion on the rocky shores of west Wales. A close relative of the true scorpion, it is a few millimetres long and while being quite common, is rarely seen because of its size. I struggled to find it but on this occasion, I took a photo on a Fuji bridge camera and for the 4 or 5 magnification, I had a 50mm SLR lens reversed over the front (a technique called coupling). Until very recently if you Googled this little arachnid, only my rather soft photo appeared as I had it on an educational website. What this illustrates is that we are passing a vast array of species every second of the day, but very few photographers are taking advantage of that bonanza. Instead, like landscape photographers travelling to the classic honeypot sites, there are the nature photographers imaging the big stuff. I am not complaining as I do the same.

Part of my life-long career in biology has been to educate children across the world in conservation issues. Once I stood up in a Singaporean auditorium and talked to a thousand teenagers, asking them, What is the point of a panda? Given the choice, would you conserve the panda or a bluebottle fly?, daring them to understand that if we lost pandas the world would carry on; a very sad and genetically poor world, but one that would survive. You can imagine the uproar. Flies are not cuddly creatures and so do not tug at the conservation heartstrings. We need flies to clear up our world of the dead and decaying, not to mention the mountains of dung produced. For the sake of conservation I believe we should be highlighting the wildlife that is so hidden. Entering the realm of the micro-world is such a clich but it is also very true that it is an exciting, alternative world which so few people ever get to see, let alone photograph. The problem is down to the difficulty of taking photos of very small things and I have tried here and in previous books to redress this problem.

Next page