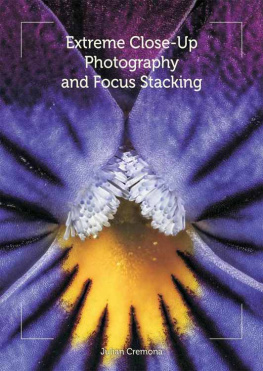

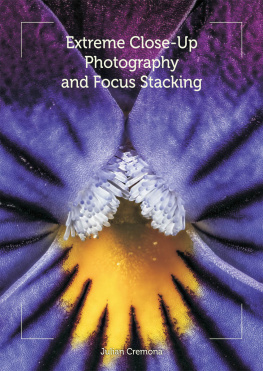

Extreme Close-Up Photography

and Focus Stacking

Julian Cremona

First published in 2014 by

The Crowood Press Ltd

Ramsbury, Marlborough

Wiltshire SN8 2HR

www.crowood.com

This e-book first published in 2014

Julian Cremona 2014

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopy, recording, or any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publishers.

British Library Cataloguing-in-Publication Data

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

ISBN 978 1 84797 720 5

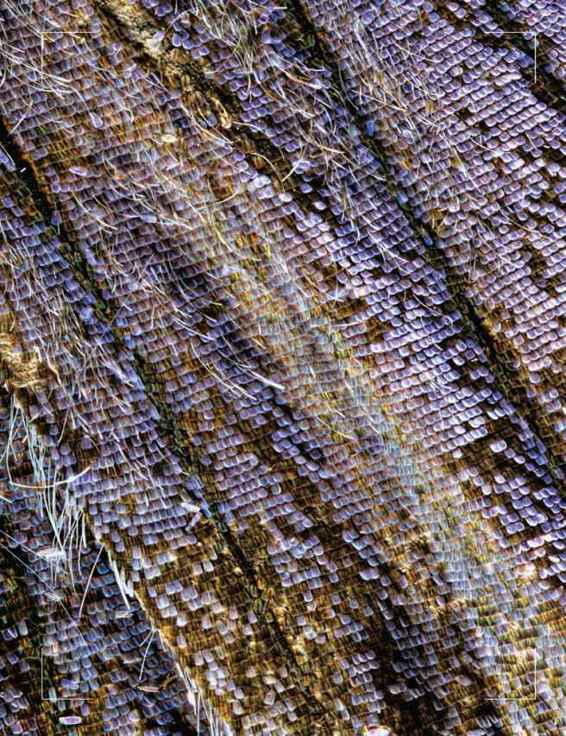

Frontispiece: Close-up of the hind wing of a Common Blue Butterfly Polyommatus icarus, male, 4.

Dedication

This book is dedicated to my bug collectors Carys, Rory, Conor and Finlay.

Acknowledgements

Much of what I have learnt over the years has been down to trial and error. In recent years a number of people that I have met have triggered ideas through conversations and given support, like John Archer-Thomson, a landscape photographer, friend and work colleague. Mike Crutchley, a retired engineer, develops great ideas, some of which brush off onto me. Often through a collective discussion, ideas are generated. Some of the super ideas people are from the Quekett Microscopy Club. In particular are Phil Greaves, Geoff Mould, Carel Sartori, Ray Sloss and Spike Walker. Thanks to all of them for their thoughts and suggestions over the years. Also to James Robson of the Horniman Museum in London: always one for a bargain on eBay! My family has been a constant support, especially my four super grandchildren who show such brilliant enthusiasm for the natural world at a young age. Thanks especially to Brenda, my long-suffering wife, who has always been my greatest supporter and critic.

CONTENTS

Introduction

I have always been a collector: even at the age of eight I collected any object pertaining to wildlife. By ten years of age this collecting advanced to pickling pieces and parts of bodies, such as the heart of a dead bird. By twelve I was setting butterflies and other insects on boards. The collecting had now taken on a whole new angle as I discovered the use of crushed laurel leaves to produce cyanide to bump off all the invertebrates in the back garden. The collection grew during my teenage years until my parents asked me why I had to kill everything. It was for my eighteenth birthday they bought me a camera and suggested I photograph them instead. The camera was one of the most difficult to use, but a cheap, single-lens reflex model: a Russian Zenith E. Gradually, as I learnt to use the camera my collecting changed again and has continued for more than forty years. My huge invertebrate collection is now on a computer and easier to access through a database. This digital image may not appear as exciting as the tangible object and yet the thrill of capture is no less electrifying. When exploring a new location the sight of a species I have never seen before provides the same level of excitement, so that as I move in with the digital SLR I am shaking. I stop breathing as I fire the shutter to capture the creature. It will start with a general distant shot with the habitat in the background and, by slowly moving closer, just the organism is collected. That is not good enough as I need to see the detail of wings and hairs on the legs. Every invertebrate has a personality, which the portrait photograph shows, and so the collection will not be complete until that head shot is in the bag.

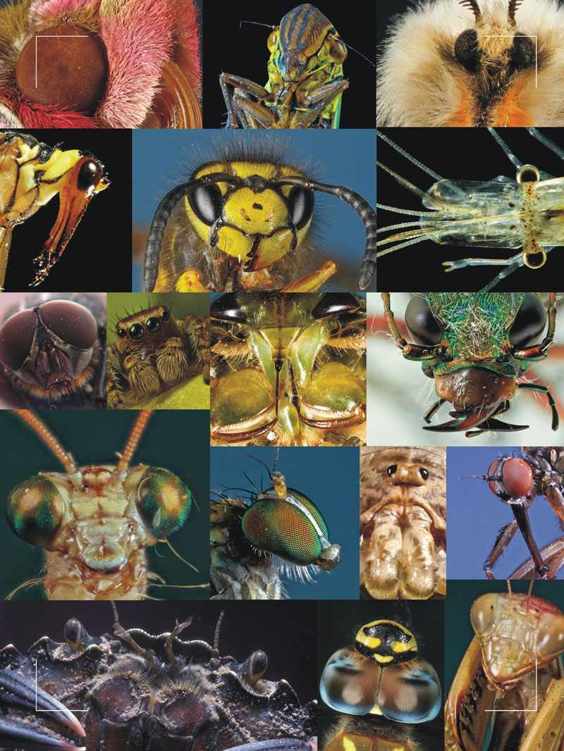

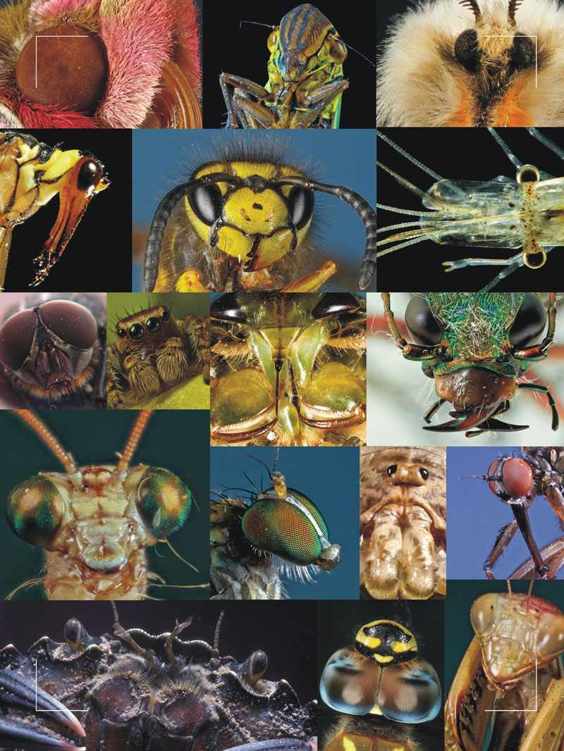

Fig. 0.1

Portraits of different invertebrates. Left to right, top to bottom: Elephant Hawkmoth, Froghopper, White Ermine Moth, Scorpion-fly, Wasp, Prawn, House Fly, Jumping Spider, Saucer Bug, Tiger Beetle, Mantis Fly, Dolly Fly, Harvestman, Empid Fly, Common Shore Crab, Migrant Hawker, Praying Mantis.

Those early days with the Zenith were a struggle with minimum finance. Film was bought in bulk, cut up and loaded in the darkroom. I learnt at university to process my own, using the zoology departments darkroom at night when no-one else needed it. Most difficult was teaching myself ways of taking close-ups and getting those head shots with no money to buy equipment. Toilet rolls, poster rolls, lenses borrowed from student microscopes and slide projectors as spot lights all were used and developed until I had vaguely presentable images. I gave many people a good deal of enjoyment as they laughed at my methods. Today I would cringe at some of the results and yet the Zenith was a superb learning tool because of the difficulty in getting good results. Every day seemed to be a back-to-the-drawing-board day as I developed the film and went back to try again. Today learning is easier, with near-instant results.

There is staggering beauty in the unseen elements of nature in close-up. I never cease to be amazed as details appear in a focus-stacked image which the unaided eye could not resolve. During my life as a biologist I have learnt and been lucky enough to branch into every area of the natural world, not just terrestrial invertebrates but to extend my collection in directions I never would have thought possible as a young teenager.

Embracing and developing new technologies to achieve this is ongoing. Relatively speaking, the price of equipment has never been lower, and products are more accessible with the Internet. Some new ideas can lead to a dead end and that can make people afraid of trying, concerned about getting it wrong. As has often been the case in history, most of what I have learnt has been through such mistakes. Sometimes I am pleased with particular images but typically I am not and always feel that I need to try again.

The digital vs. film debate still goes on which is better? I suppose it depends on ones viewpoint but I would never return to film, for environmental reasons and because I spent many years in darkrooms breathing in the noxious chemicals. In addition there are the improved methods of capturing close-ups and more advanced ways of learning to improve. I hope that this book will help you develop more quickly than I did. There is no better time than now to create extreme close-ups, and the technology is straightforward. Although it would be great if a student of photography could learn everything in one go, until that becomes possible, the linear fashion of chapters building upon each other is the way this book is written. The contents show the key points; dip in and out to suit yourself. The final chapter is the one that tries to piece it all together by taking specific subject matter and looking from that perspective. The choice of organisms has been made to cover most eventualities.

Today I have a catalogue of many thousands of species, digitally stored on my hard drive, which I have collected over my life. It may not be as spectacular as a museum collection but at least I no longer need to kill species to store them. Focus stacking has been described by many who practise it as only possible when using dead specimens. Unless I find the individual already dead, I rarely use dead material. Unless stated, all photographs were taken of living specimens.

This book is approached from the perspective of a naturalist wanting a record of any organism they find. It is about attaining maximum detail and sharpness. It is a practical guide covering all aspects of how to photograph any terrestrial or aquatic subject in close-up. Where possible, captions give some information about the organism. What sets this book apart, however, is its focus on providing the most concise information available to date on focus stacking, and it will be useful for anyone interested in this topic, whether for macro or any other form of photography, such as landscapes.