Contents

Guide

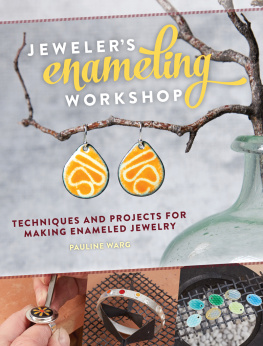

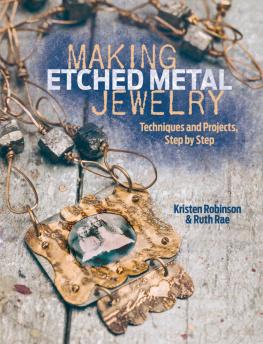

Techniques and Projects for Making Enameled Jewelry

Pauline Warg

This book is dedicated fondly to Stell Shevis and Woodrow Carpenter for their contributions to the world of enameling and for providing endless inspiration.

CONTENTS

Introduction

At the tender age of seven, I was given a Trinket enameling kit by my favorite uncle. My parents let me set up a little studio in the basement of our home. I read and experimented with all the techniques described in the pamphlet that came with the kit. I was quite productive, making gifts of bowls, pins, pendants, and earrings for family members. That kiln gave me hours of enjoyment for many years, and I taught myself the basics of sifted enamels using it. After a few years I became distracted by other aspects of growing up, and the Trinket box became dusty.

Fast-forward to my college years. I became a classically trained jeweler and metalsmith in a unique and intensive European apprenticeship-style program. In addition, I later completed a BFA. While I was steeped in my metalsmithing training, I dreamed of learning more about enameling. I especially loved Ren Laliques work and plique--jour. Someday...

My career as a metalsmith and jeweler gave me the opportunity to study the finer techniques of cloisonn, champlev, and plique--jour with masters of these skills. I was able to add a whole range of enameling skills to my jewelry-making repertoire and was thrilled with the growth I was able to make through using these advanced enameling skills.

Enameling has been a journey of excitement and diversity. I love being able to add color to my work without necessarily using gemstones. There is a painterly quality to enameling that I enjoy very much. It is also a very meditative process. It is quiet, close, and thoughtful.

Enameling is an amazingly expansive technical area. It would be nearly impossible to cover every aspect thoroughly in one book. I hope to share a great deal of my knowledge of the techniques I have learned and with which I am more experienced. Many of the projects within are set up to engage and instruct beginners with no experience in enameling or metalsmithing. The projects move forward to include more advanced enameling and more involved metalsmithing skills.

Anyone interested in learning the art of enameling as a beginner and those with some experience who wish to expand their knowledge should gain from the content of this book.

Enjoy!

Enameling Basics

Enameling is a broad topic that covers a myriad of techniques in which powdered glass is applied to a metal surface and fused at high temperatures. The following section breaks these processes down step by step and covers all the tools and supplies youll use to demystify enameling and ensure your projects are successful.

Enamels come in a wide range of colors, in both transparent and opaque forms.

Chemistry and Characteristics

The enamels I use in this book and those I teach with are called high-fired, or hard-fired, enamels, not to be confused with enamel as in oil-based paint. They consist of clear glass mixed with chemicals and/or metals to give the glass pigment, or color. These enamels melt at about 1,450F (788C). The enamels used mostly in jewelry making are called medium-temperature/medium-fusing enamels.

Types of Enamel

There are several brands of glass enamels made for jewelry enameling. In this book, I will be using Thompson brand unleaded, or nonleaded, enamels, but other medium-temperature enamels can be used in the same way. Colors may vary from brand to brand.

Chemists have developed recipes to create different colors of powdered glass for enameling. The enamels start with pulverized clear glass.

Different chemicals and/or metal powders are added to that clear glass to create a specific color. For instance, there may be cobalt in some blue enamel and gold in red enamels. This mix is then remelted, cooled, and then re-pulverized to make the enamel powder. Most typically the glass is pulverized to what is called 80 mesh. Mesh is the term used to describe the grain size of the enamel, and 80 mesh looks similar to, but a bit finer than, granulated sugar.

Glass enamel powders do not mix to make additional colors. For example, blue enamel and yellow enamel grains mixed together do not make green enamel. If you fired them, the result would be speckles of blue and speckles of yellow. The grains of each color will maintain their individual integrity. Therefore, its very important not to contaminate one dry enamel with another.

There are leaded and unleaded enamels, and both come in transparent colors and opaque colors. The primary difference between the two (leaded and non) for use in jewelry making is the accuracy of color in the warm range of transparent colors on silver. Some nonleaded transparent yellows, reds, and purples turn dark or brown when used on silver. This does not happen as much or as severely when leaded transparent warm-range colors are used on silver. This chemical reaction of nonleaded enamels on silver is a good reason to make a color sample board for reference.

Firing Enamel

Most medium-temperature/medium-fusing unleaded enamels fire (melt) at about 1,450F (788C). The temperature may vary slightly from color to color. An enamel that melts at 100F (38C) more than 1,450F is called a harder enamel. One that melts slightly below 1,450F is called a slightly softer enamel. The 1,450F is an average at which these enamels fire.

When firing these enamels, whether with a torch or in a kiln, there are stages the enamel goes through until it becomes completely fired.