About the Author

Cliff Jacobson is one of North Americas most respected outdoors writers and wilderness canoe guides. He is a retired environmental science teacher, an outdoors skills instructor, a canoeing and camping consultant, and the author of more than a dozen top-selling books on canoeing and camping. He is a recipient of the American Canoe Associations prestigious Legends of Paddling Award and a member of the ACA Hall of Fame. He lives in River Falls, Wisconsin.

CHAPTER 1

Choosing Rope

T o most people a rope is a rope, and they make no distinction between natural or synthetic fibers. Thats too bad, because certain rope materials and weaves excel in certain applications. The following are some things to consider when choosing ropes.

Flexibility. Flexible ropes accept knots more willingly than stiffer weaves, but when coiled they are more likely to twist and snag. Choose flexible ropes for tying gear on cars, for general utility, and wherever a proper lashing is needed. Ropes with a stiff hand are best for lifeguard throwing lines and use around water.

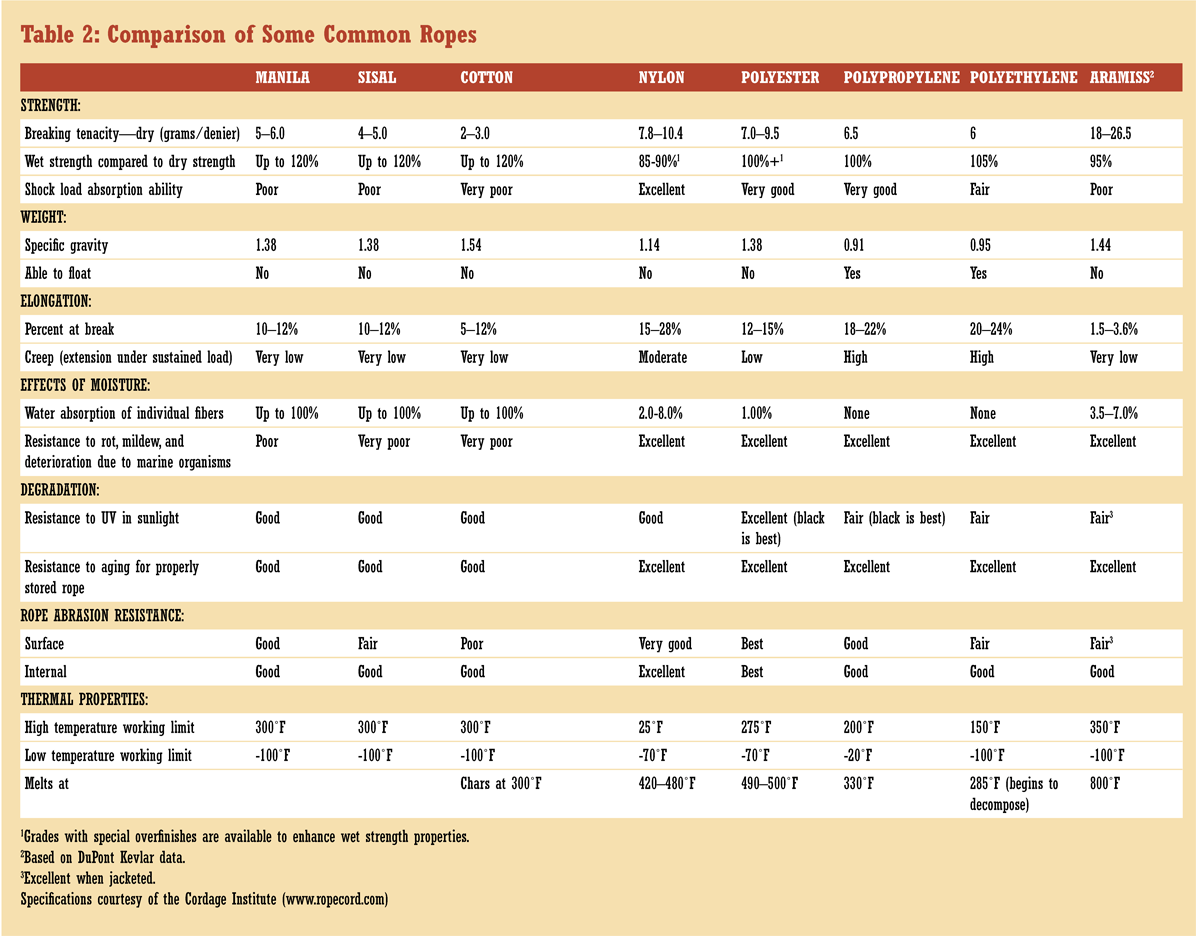

Slipperiness. A slippery rope is always a nuisance. Polyethylene and polypropylene ropes are so slippery that they retain knots only if you lock them in place with a whipping or security hitch.

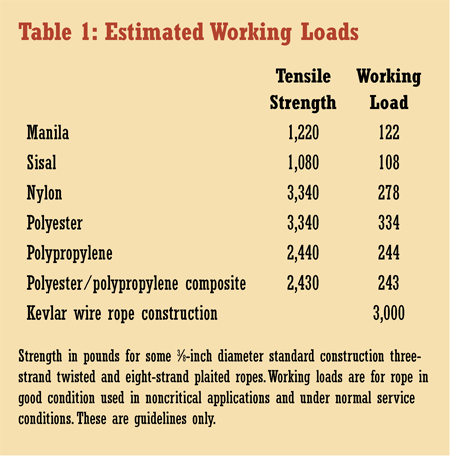

Diameter versus strength. The rule of thumb says that if you double the diameter of a rope, you quadruple its strength. This estimate can be refined with tabular data from the Cordage Institute (www.ropecord.com). For comparison: New -inch three-strand nylon rope yields a tensile strength of 1,490 pounds; -inch nylon rope of similar construction tests at 5,750 pounds.

Safe working load. Safety factors and working loads are not the same for all types of rope or applications, so it is not possible to accurately define safe working load. The important thing to remember is that estimated working loads like those listed in table 1 are simply guidelines to product selection. They naturally assume that ropes are in good condition and are being used in noncritical applications under normal service conditions. Suggested working loads should always be reduced where there is danger to life or property or when the rope will be exposed to shock or sustained stress.

Memory. The ability of a rope to retain a coiled or knotted shape is called memory. Lariats and throwing lines must necessarily remember their manners or theyll snag when played out. Generally, stiffness and good memory go hand in handbut not always. For example, polyethylene line is very flexible, but it never forgets its store-bought windings. Most high-memory ropes dont take knots very well.

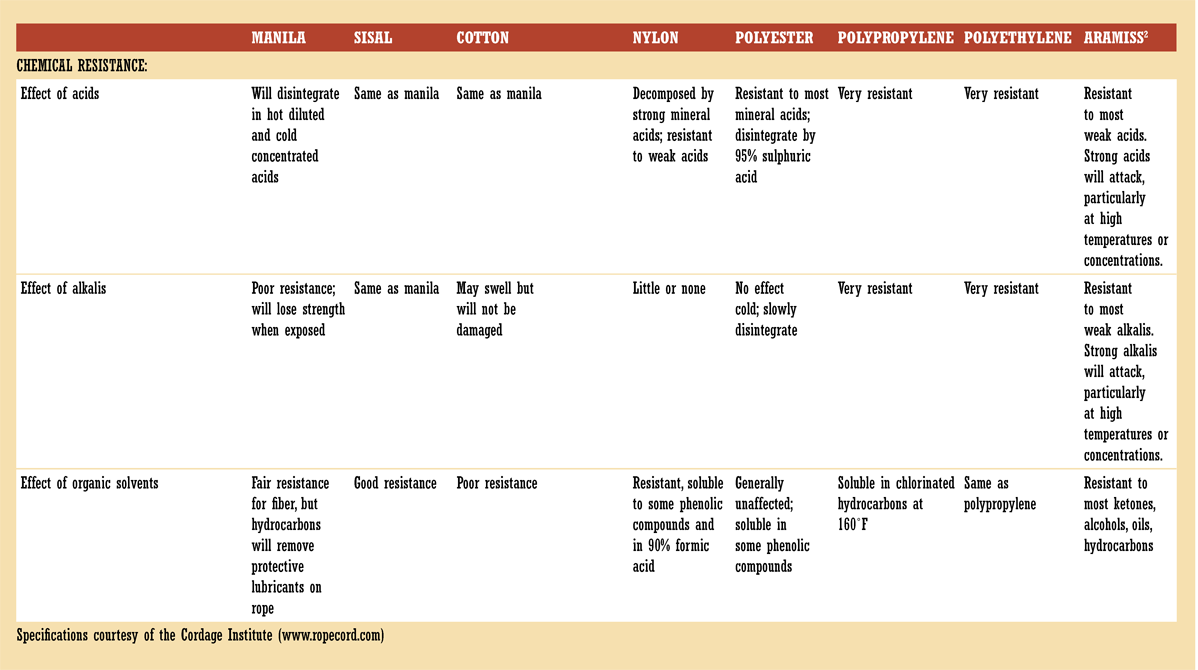

Ultraviolet degradation. This is important to consider if your ropes are exposed to sunlight for long periods of time. Table 2 on the next two pages provides the comparative specifics.

Stretch. Towing and mountaineering work demand a stretchy rope; tie-down applications require the opposite. Natural-fiber ropes (such as manila, hemp, and sisal) shrink when wet, while nylon ones stretch under load. Forty years ago, campers faithfully loosened natural fiber tent guylines each night before they retired. Todays campers tighten nylon ropes when the sun goes down and several times during a storm.

Floatability. Polypropylene and polyethylene (which float) are the logical choices for water-ski ropes and throwing lines.

Effects of chemicals. Spill insect repellent on polypropylene rope and youll have a handful of mushy fiber. All ropes are affected to some degree by harsh solvents.

Types of Rope

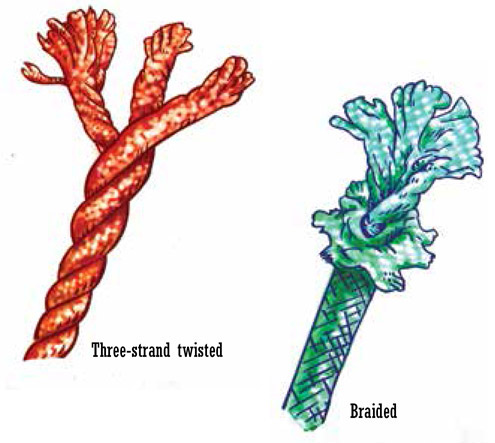

Nylon. The most popular rope fiber, nylon is strong, light, immune to rot, and shock absorbent. The most popular weaves are three strand twisted and braided or sheathed (figure 1). Twisted rope strands unravel when heated and are therefore difficult to flame-whip when cut. They are best whipped with waxed string, plastic whipping compound, or heat-shrunk plastic tubing.

Braided (sheathed) rope is actually two ropes, one inside the other. Its wonderfully pliable, and it resists twists and kinks when coiling. Braided rope flame-whips easily, and its casing resists abrasion; however, its sheath may mask flaws in the core.

Figure 1

Polyethylene. Inexpensive, slippery, slightly elastic, unaffected by water, available in colors, and it floatspopular for towing water-skiers.

Polypropylene. Similar to polyethylene but less slippery and more elastic (a better rope). Abrasion, ultraviolet light, and heat are major enemies of plastic (polypropylene and polyethylene) ropes. Not all polypropylene cordage is the same. Some types (notably baler twine) have ultraviolet inhibitors and can hold knots without slipping.

Polyester (Dacron) is the material for sailboat sheet and mooring lines and every place you need a rope that is dimensionally stable and resistant to ultraviolet light. Unlike nylon, polyester rope retains all of its strength when wet (see table 2), which is the reason sailors like it. You can get prestretched polyester rope for special applications that require extreme dismensional stability.

Natural-fiber ropes. Except for cotton, which is still used for sash cords and clothesline, natural-fiber ropes such as manila, sisal, hemp, and jute have almost gone the way of the passenger pigeon. Natural fibers have a nice hand; they coil well and hold knots tenaciously. But they rot easily and for their weight arent very strong. For example, the tensile strength in pounds of new manila rope is roughly 8,000 times the square of its diameter in inches. Thus, new -inch manila will theoretically hold about .375 x.375 x 8,000 = 1,125 pounds (the Cordage Institute figure is 1,220)hardly a match for the modern synthetics in table 1.

Kevlar is a gold-colored synthetic fiber developed by DuPont. Its used as a tirecord fiber, for bullet-resistant vests, and as fabrication material for ultralight canoes and kayaks. Kevlar rope is very light (its specific gravity is 1.44); its about four times as strong as steel of the same diameter, and it is so expensive that its recommended only for applications where extreme strength, light weight, low elongation, and noncorrosion are major concerns. Kevlar is difficult to cut, even with the sharpest tools.

Ten Most Important Knots and Hitches

Anchor (fishermans) bend

Bowline

Butterfly noose

Clove hitch

One half hitch/two half hitches

Monofilament fishing knot (clinch knot)

Power cinch (truckers knot)

Quick-release (slippery) loop

Sheet bend/double sheet bend/slippery sheet bend

Timber hitch

Preparing a New Rope

I wouldnt think of striking off into the backcountry without one or two 50-foot hanks of -inch twisted nylon rope. On occasion, my ropes have served to extract a rock-pinned canoe from a raging rapid; to rig a nylon rain tarp in the teeth of a storm; as a strong clothesline and swimmers rescue rope; to secure gear on my truck; and once to haul my old Volkswagen Beetle out of a knee-deep ditch.

A well-maintained rope may last a decade. An ill-kept one wont survive a season. First order of business is to seal the ends (called whipping) by one of the following methods, so they wont unravel: