WHILE WRITING THE history of bacon, I applied the same standards to my own work as I did when working as a research assistant to a history professor. Such strict requirements regarding sources and citations, however, did result in the exclusion of some excellent stories. For example, it is claimed (by numerous people) that a fence had to be erected to keep pigs out of certain parts of Manhattan, and that this fence became known as Wall Street. The journalist in me wants to include this nugget, but the honest historian won out. There are simply too few sources to support the story.

I didnt manage to note all my sources while I was working (as a diligent historian does automatically and without exception), so the following bibliography is far from comprehensive. Much of the history is readily accessible, such as the information on Columbus voyages, the colonisation of America, and the Industrial Revolution in Britain. Below are some of the most important sources for information on pigs, generally, and bacon in particular. Some of the sources are noted within the text (in which case they are omitted here).

ON THE EARLY HISTORY OF BACON

There are still many aspects of the domestication of pigs that we dont know a great deal about. An interesting article on the BBCs science website tells us that European pigs originated in the Middle East, according to DNA evidence uncovered by researchers. In Europe we then saw a new wave of domestication of European wild boars. This happened at some point between 7,000 and 4,000 BC .

The Middle Eastern breeds were gradually supplanted and the newer European pigs eventually spread to the Middle East. This is just a hypothesis, but I derived much of the information from this article: http://news.bbc.co.uk/2/hi/science/nature/6978203.stm.

www.touregypt.net/featurestories/pigs.htm gives some information on the early history of pigs in Egypt.

Mark Essigs book Lesser Beasts: A Snout-to-Tail History of the Humble Pig, Mark Essig (Basic Books 2015), was an invaluable resource concerning the history of pigs. Many thanks to Mark, who was also very helpful in answering my questions!

www.history.org has several excellent articles on pigs and on the preservation of food by salting and smoking throughout history.

BACON IN ENGLAND

I used many sources to research the early history of bacon particularly useful was The Agrarian History of England and Wales: Prehistory by H.P.R. Finberg, Joan Thirsk (Cambridge U.P.)

The easily accessible public archive at www.railwaysarchive.co.uk was helpful regarding the history of pigs in England and Ireland. On the development of railways in Southern England, the well-documented feasibility studies were useful (they were carried out using more or less random interviews). There are some in Extracts from the Minutes of Evidence Given Before the Committee of the Lords on the London and Birmingham Railway Bill from 1832, for example.

There is also plenty of worthwhile reading in Penny Magazine by the Society for the Diffusion of Useful Knowledge, Volume 12 from 1843.

When it came to information on the Harris family, the article on the subject at www.british-history.ac.uk was a great help.

For those particularly interested, there are actually clips on YouTube, where you can watch the demolition of the fabled bacon factory itself.

I also used Encyclopaedia of Meat Sciences by Carrick Devine, and M. Dikeman (Academic Press, 2004).

BACON IN AMERICA

The monumental academic work on the arrival and role of pigs in the New World has, alas, yet to be written. In the meantime, I fell back on a broad and varied array of articles and books. Among them was The Iberian Pig in Spain and the Americas at the time of Columbus at www.bzhumdrum.com/pig/iberianpig-intheamericas.pdf .

There are innumerable sites where small pieces of more or less reliable information crop up. A random example is www.austinchronicle.com/food/2009-04-10/764573/ , which relates the history of the pig in America. Ive fact-checked and attempted to investigate sources for as much of this as I can. The result is the narrative Ive assembled in this chapter, and the buck stops with me.

Ann Ramenofsky and Patricia Galloway claim in an article entitled Sources for the Hernando de Soto Expedition: Intertextuality and the Elusiveness of Truth that pigs were the cause of the demographic collapse of the indigenous population, particularly by spreading diseases to which the natives lacked immunity (unlike the Europeans). More of this sort of thorough historical analysis would have made the job a lot easier.

THE PIGS OF NEW YORK

Particularly worth reading is Pigs in New York City; a Study on 19th Century Urban Sanitation, [SIC] by Enrique Alonso and Ana Recarte www.institutofranklin.net/sites/default/files/fckeditor/CS%20Pigs%20in%20New%20York.pdf

In the section on modern bacon, the excellent Putting Meat on the American Table: Taste, Technology, Transformation by Roger Horowitz (The Johns Hopkins University Press, 2005), was a great help. Many thanks to Roger, who also responded kindly to my odd questions. Another useful site was www.porkbeinspired.com.

OTHER SOURCES

The have been consulted frequently.

Photographs and illustrations not taken or drawn by the author are taken from www.thinkstock.com .

Visits to Grilstad in Brumunddal and FG Kjttsenter in Groruddalen, along with the two trips to Norsvin in Hamar, have contributed to my understanding of the effort it takes to bring us proper bacon. A farm visit to Harald Gropen at Lken stre was brief but enjoyable.

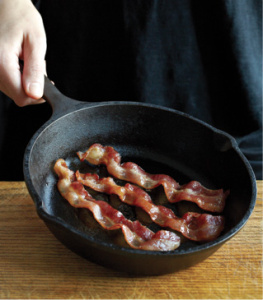

A MAN CROUCHES behind a rock and raises his arm silently. He has a spear clutched firmly in his right hand, tipped with the sharpest stone he could find. In the clearing before him a pig is grunting with pleasure, burrowing eagerly into some promising roots. Its lost in the task, paying no heed to its surroundings.

The hunter rises to his feet to get enough power behind the throw, lifting himself into a standing position as slowly, as carefully, as he can. The moment has come.

It happens fast. He tenses his body, hurling the spear with all the strength he can muster. The pig senses something is wrong the moment the spear leaves the hunters hand. It suddenly stops digging and turns its head to face the hunter, their eyes meeting for a fraction of a second. Moving by reflex alone, the pig leaps forward, escaping the deadly projectile by millimetres. It squeals loudly and within seconds it disappears into the bushes, out of sight. The hunter listens as it escapes into the forest. The proud hunter slouches home, tired, hungry and frustrated. He knows that his children are even hungrier than he is. Story of my life, he mutters to himself. Its bad for me and its worse for the kids. Its been days since he brought home any meat.

The next morning, he wakes feeling strangely determined. Hes had enough. Hes sick of chasing his prey through the woods. The pigs are fast and persistent and nigh-impossible to outwit. They can literally smell him coming, long before he can so much as lay eyes on them. There must be a smarter way to do this. There must be some way to avoid this constant need to hunt, while still getting to have as much meat as he wants.

This weary, frustrated man lived by the river Tigris, and its him we have to thank for bacon. It may have taken another 1,000 years or more before we were tucking into rashers of thin bacon for breakfast, but without pigs, there would be no bacon.

You can salt and smoke rashers of beef, mutton, goat, reindeer, moose or rabbit, as much as you like, but theyll never be bacon.

Next page