CONTENTS

INTRODUCTION

It has long been a dream of mine to write a book on miso. Had a version of this book existed when my obsession with this amazing ingredient first took hold though, I would never have embarked upon the incredible, life-changing journey that I did. Now I want miso to become your best friend in the kitchen too, ready to add instant depth, texture and nutrition to your food. Im certain it will delight and entrance you as much as it has me.

I was always puzzled by the limited choice of miso on offer in the UK: how could something so central to Japanese cuisine be so little-known outside of that country? I was forced to bridge the gap. Now, my business, Miso Tasty, makes authentic miso products, teaches the benefits of eating this ancient foodstuff and inspires its use in everyday cooking. This book is part of my mission to educate people about miso.

It took three long years to source and make my own miso products; a period of my life that was fuelled by a stubborn determination and enthusiasm, but was also peppered with endless unexpected setbacks. Looking back, though, it was an important journey and a critical lesson in perseverance that has been reflected in the craft of every miso maker Ive met.

As a miso geek, I have visited century-old factories, dropped in on producers at their homes and at specialist stores in Japan to ask all my questions. Even today, with every trip to Japan, I discover new makers and novel ways to enjoy miso.

While I am often cited as the UK expert on miso, I see myself firmly as a dedicated student and impassioned enthusiast of miso. I am in awe of the real experts and makers of miso in Japan from whom I continue to learn. I see my role more as a communicator for miso outside of Japan, where I continue to extol its virtues and share my ideas, research and experiences in using this ancient cooking ingredient.

Miso can and should play a vital role in your kitchen. The recipes within these pages are a mix of well-loved classics and new discoveries. You will find all the dishes that you know and love, as well as some more creative uses that will surprise even the most adventurous eater. Once you have tried these dishes, I hope you will gain the confidence to experiment with miso in your own creations, too. If you find yourself often reaching for a jar of miso, then I would consider my mission for this book accomplished. Enjoy!

WHAT IS MISO?

Miso is quite unlike anything else. Essentially, it is a fermented soybean paste made with a grain such as rice or barley, salt, water and a bacterial culture called Aspergillus oryzae. But, though the ingredients are simple, the transformation they undergo is extraordinary.

As with other fermented foods, such as cheese, kimchi or sauerkraut, the flavour of miso becomes more complex the longer it is fermented. The smell is distinctive: when you walk into a miso store in Japan, you are greeted by a heady cloud of fragrance, like freshly roasted coffee or melted dark chocolate.

The bible of Japanese food and culture, Japanese Cooking: A Simple Art by Shizuo Tsuji, says that, in many ways, miso is to Japanese cooking what butter is to French cooking and olive oil to the Italians. I have to agree that its just as ubiquitous.

The first records of miso are from more than 2,500 years ago. It was probably brought to Japan by Buddhist priests from China during the 7th century. At the time, using fermented mixtures of salt, grains and soybeans was a key way to preserve food during warmer months, and this practice formed the backbone to miso-making. The original Chinese soybean paste was transformed in Japanese cuisine into miso and shoyu (Japanese soy sauce); two hallmarks of the countrys food.

Interestingly, there was historically an element of class concerning who ate which kind of miso. Wealthy landowners, royalty or samurai would only eat rice miso that had been made using expensive polished white rice. It was often so expensive that it was used as gifts, or even as currency. Peasants and farm hands were forbidden to use the rice they harvested to make their own miso, so used any broken rice, or other grains such as millet and barley. This explains why darker miso made from these grains has a reputation, even today, as poor mans miso.

A typical miso store in Japan will hold collections of over 30 types of miso from around the country. Samples can be tried before purchasing by weight.

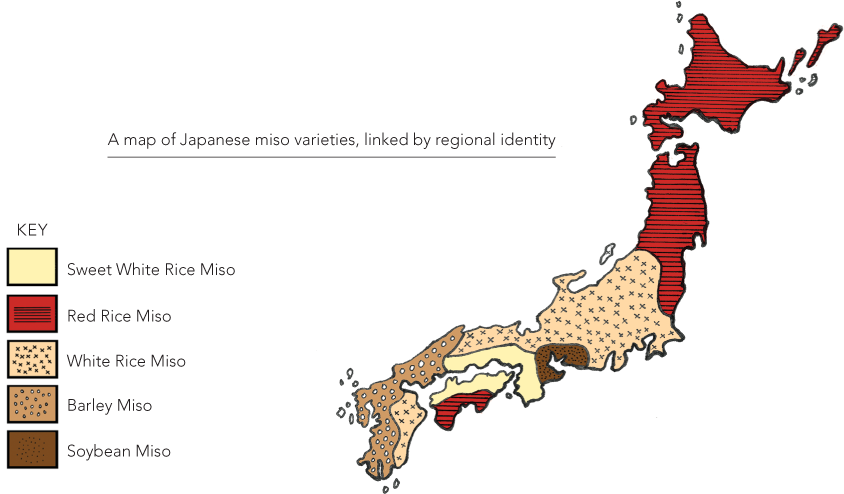

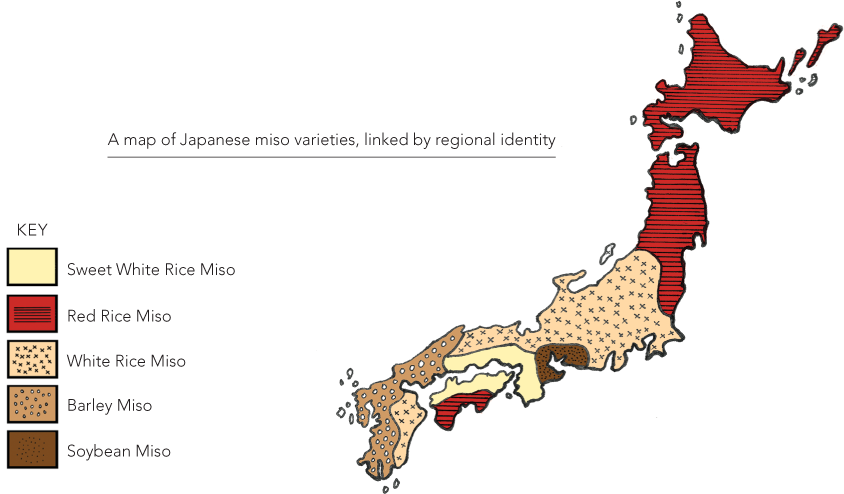

There are more than 1,000 miso producers in Japan and there are wide regional differences. Northern regions, where most of the countrys rice is farmed, tend to prefer rice misos; the ancient capital of Kyoto loves the more refined sweet white miso; the area surrounding the Aichi prefecture likes pure soybean miso; while the southern regions opt for barley miso or miso made from other grains.

In Japan, there is a lovely saying, temae miso, which means to blow your own trumpet; literally, I dont want to boast about my miso but. This is an unusual sentiment in Japanese culture, where humility is valued; but when it comes to pride in your home-made miso, modesty is abandoned!

Today, in kitchens both in Japan and across the world, miso holds endless possibilities in both traditional and modern dishes: swirl it into a hot stock for miso soup, mix it with a drop of olive oil and a spoon of mustard for a deeply satisfying salad dressing, or baste it on to steaks for a quick but deeply flavoured barbecue marinade.

For me, miso is the ancient cupboard staple I cant live without.

HOW IS MISO MADE?

Miso is made from only a few simple ingredients but, after hundreds of years of refinement, miso-making has become a special craft.

First of all, soybeans are steamed or boiled and a fermentation starter, a koji mould, is applied. The koji is the key ingredient to the magic of miso, a fungus specially bred for the purpose, grown on steamed rice, barley or beans.

The mixture is then left for the koji to multiply. The grains and beans are then mashed together, mixed with sea salt and spring water and the mixture left in a cedar barrel to ferment. The fermentation is largely carried out by the koji mould, but is also helped by the hundreds of kinds of bacteria living in the barrel, adding their own nutrients. When the koji starts its work on the fermentation process, it heats up, but it must be kept under 40C (104F) as its enzymes first turn the starch into sugar and then break the beans down into amino acids. A heavy weight is put on top to reduce any contact with air during fermentation.

Next page