Selin Kiazim - Oklava: Recipes from a Turkish–Cypriot Kitchen

Here you can read online Selin Kiazim - Oklava: Recipes from a Turkish–Cypriot Kitchen full text of the book (entire story) in english for free. Download pdf and epub, get meaning, cover and reviews about this ebook. year: 2017, publisher: Octopus, genre: Home and family. Description of the work, (preface) as well as reviews are available. Best literature library LitArk.com created for fans of good reading and offers a wide selection of genres:

Romance novel

Science fiction

Adventure

Detective

Science

History

Home and family

Prose

Art

Politics

Computer

Non-fiction

Religion

Business

Children

Humor

Choose a favorite category and find really read worthwhile books. Enjoy immersion in the world of imagination, feel the emotions of the characters or learn something new for yourself, make an fascinating discovery.

- Book:Oklava: Recipes from a Turkish–Cypriot Kitchen

- Author:

- Publisher:Octopus

- Genre:

- Year:2017

- Rating:5 / 5

- Favourites:Add to favourites

- Your mark:

- 100

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Oklava: Recipes from a Turkish–Cypriot Kitchen: summary, description and annotation

We offer to read an annotation, description, summary or preface (depends on what the author of the book "Oklava: Recipes from a Turkish–Cypriot Kitchen" wrote himself). If you haven't found the necessary information about the book — write in the comments, we will try to find it.

Oklava: Recipes from a Turkish–Cypriot Kitchen — read online for free the complete book (whole text) full work

Below is the text of the book, divided by pages. System saving the place of the last page read, allows you to conveniently read the book "Oklava: Recipes from a Turkish–Cypriot Kitchen" online for free, without having to search again every time where you left off. Put a bookmark, and you can go to the page where you finished reading at any time.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

Oklava translates simply as rolling pin. When I think of an oklava it always conjures up memories of my nene (grandmother): a rolling pin was never far from her hands, which always meant a delicious treat was imminent.

I was born and grew up in north London, surrounded by Turkish and Greek Cypriots. As all migrant communities seem to do, theyd all settled in one corner of London. As a result, Turkish grocers were always nearby, which made it very easy for Mum to bring us up on traditional Turkish fare, including dolmas, yahni yemek, kfte, breks and, of course, kebabs.

My parents came over to London from Cyprus in the 1970s, but our ties to the country have always remained strong. My grandparents and cousins are all there, and our family has lived on the island for generations.

Thanks to its strategic location in the eastern Mediterranean, Cyprus has been ruled by many nations and settled by many cultures over the centuries. It has had Greek settlers for thousands of years, and in the early 1500s Turkish settlers (including my ancestors) arrived with the Ottoman Empire. Cyprus, as we now know it, has been peacefully divided in two since 1974, with the Turks living in the north and the Greeks in the south.

There is a huge amount of crossover between Turkish and Greek food. Much of it is practically the same, just with different names: for example, what is eftali to us is eftalia to the Greeks, and kfte is keftedes. The biggest difference between the two sides is that the Turks are Muslims and therefore do not eat pork, but the recipes are often essentially the same one version will use lamb and the other pork.

The food of Cyprus is all about island cooking; its simply what is grown on the land. Of course there are more supermarkets these days and some imports through Turkey, but shopping at the local market or even buying fruit and veg from roadside stalls is still very much how things are done, and in the villages they eat what they grow. Food in Cyprus is immensely seasonal, as I was reminded when looking for cauliflowers in June, while on a photo shoot for this book there werent any! And at certain times of the year, the dishes prepared in all the households will be similar. On that trip in June, a lot of the older women, including my grandmother, had black-stained hands from preparing ceviz macunu, candied walnuts. Making these is hugely laborious and takes a week. My grandmother doesnt even particularly like candied walnuts; she just makes them for the enjoyment of others!

In comparison to Turkish food with its Middle-Eastern influences, Cypriot cooking is very simple and more Mediterranean. In Turkey, with its history in the spice trade and influences from the Ottoman Empire, they use a lot more spices, as well as more nuts and dried fruits, to produce the most wonderful aromatic dishes, which can be quite rich. Cypriot flavours are simpler, ingredients lists shorter. There are also regional differences, with some areas of Turkey using butter as their main cooking fat and others olive oil.

First steps

In all honesty, I was pretty over Turkish food by the time I turned 19, which is when I enrolled at Westminster Kingsway College to study for a Professional Chefs Diploma. At college I learnt the basics of French cookery, which couldnt have been any further from Mums cooking. I loved my years at college it was the first time I felt like I was actually good at something. I was certainly never one for academic studies, but I did naturally lean towards the more creative subjects and had always loved to eat, so I guess it was perhaps inevitable that I would end up a chef.

In Cyprus with my grandfather, Kazm Doramac, my mother, Pervin Kiazim, and my grandmother, Bahire Doramac.

I started at college thinking I would learn the basics and then perhaps work as a caterer, as I was pretty petrified by the idea of being a chef in a restaurant kitchen in London. Any thoughts of being a caterer quickly disappeared when I found myself completely at home in the college kitchens and immersed in cookery books. It became an obsession, and still is. I approached one of my college lecturers, Vince Cottam, who went on to mentor me through many competitions, including one that was run by the godfather of fusion himself, New Zealand-born chef Peter Gordon. Competition day came, and that was the first time I met Peter. I was in my third and final year at college, and until then I had mostly met fairly intimidating head chefs on work experience. Now I was at the point where I needed to decide what kind of kitchen I wanted to work in. Peter was and still is the friendliest chef I have ever come across, and I knew I wanted to work for him

I won the competition and my prize was a five-week trip to New Zealand to work at some of the countrys top restaurants. One of them was Dine by Peter Gordon, in a five-star hotel in Auckland. It was during my time there that Peter offered me the opportunity of a trial at his London restaurant, The Providores. I still clearly remember walking down the stairs to the kitchen for the first time, with Peter singing to me at the top of his voice. I worked a double shift that day and loved every minute of it: everyone in the kitchen was so friendly and made sure I tried as many different flavours as possible. No-one shouting? No angry head chef? My mind was blown from day one.

Moving on.

I couldnt have dreamt of a better start to my career: I learnt such an incredible amount at The Providores, not only about food, but also about how to interact with fellow team members and create a place where people genuinely wanted to work. Leaving was tough, but I knew I wanted my own restaurant some day, so I had to keep pushing myself and climbing the ladder. There were no senior positions available at The Providores, so after two years I handed in my notice to Peter, crying my eyes out.

The job I had lined up didnt work out, and three months later I found myself working for Peter again, this time at his Covent Garden restaurant, Kopapa (now closed). After working at Kopapa as a sous chef for a year, I was made head chef. I was pretty confident in my cooking abilities at this point, but had never managed people before, so I found it a tough place to work. Again I learnt a lot, mostly about myself and my management style. Kopapa gave me a great insight into what it would take to open a new restaurant and how hard it is to make one successful.

By the end of 2012, my head was bursting with ideas and all I could think about was opening my own restaurant. I decided it was time to move on and try to make a name for myself. Pop-ups had become a big thing in London, so it seemed the natural platform for me to try it out. But before I could launch myself into the cut-throat London food scene, I had to decide what kind of food I wanted to present. I grew up in London, where the culture and the food are so diverse: it is incredibly inspiring to see people from all around the world take the humble cooking from their own countries and modernize it to work in London. The combination of my classical training at college, my Turkish-Cypriot family (including the time spent with my

Next pageFont size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

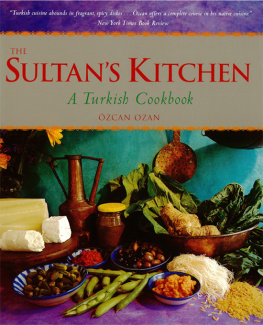

Similar books «Oklava: Recipes from a Turkish–Cypriot Kitchen»

Look at similar books to Oklava: Recipes from a Turkish–Cypriot Kitchen. We have selected literature similar in name and meaning in the hope of providing readers with more options to find new, interesting, not yet read works.

Discussion, reviews of the book Oklava: Recipes from a Turkish–Cypriot Kitchen and just readers' own opinions. Leave your comments, write what you think about the work, its meaning or the main characters. Specify what exactly you liked and what you didn't like, and why you think so.