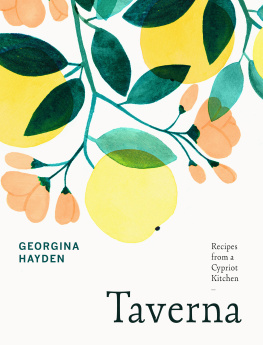

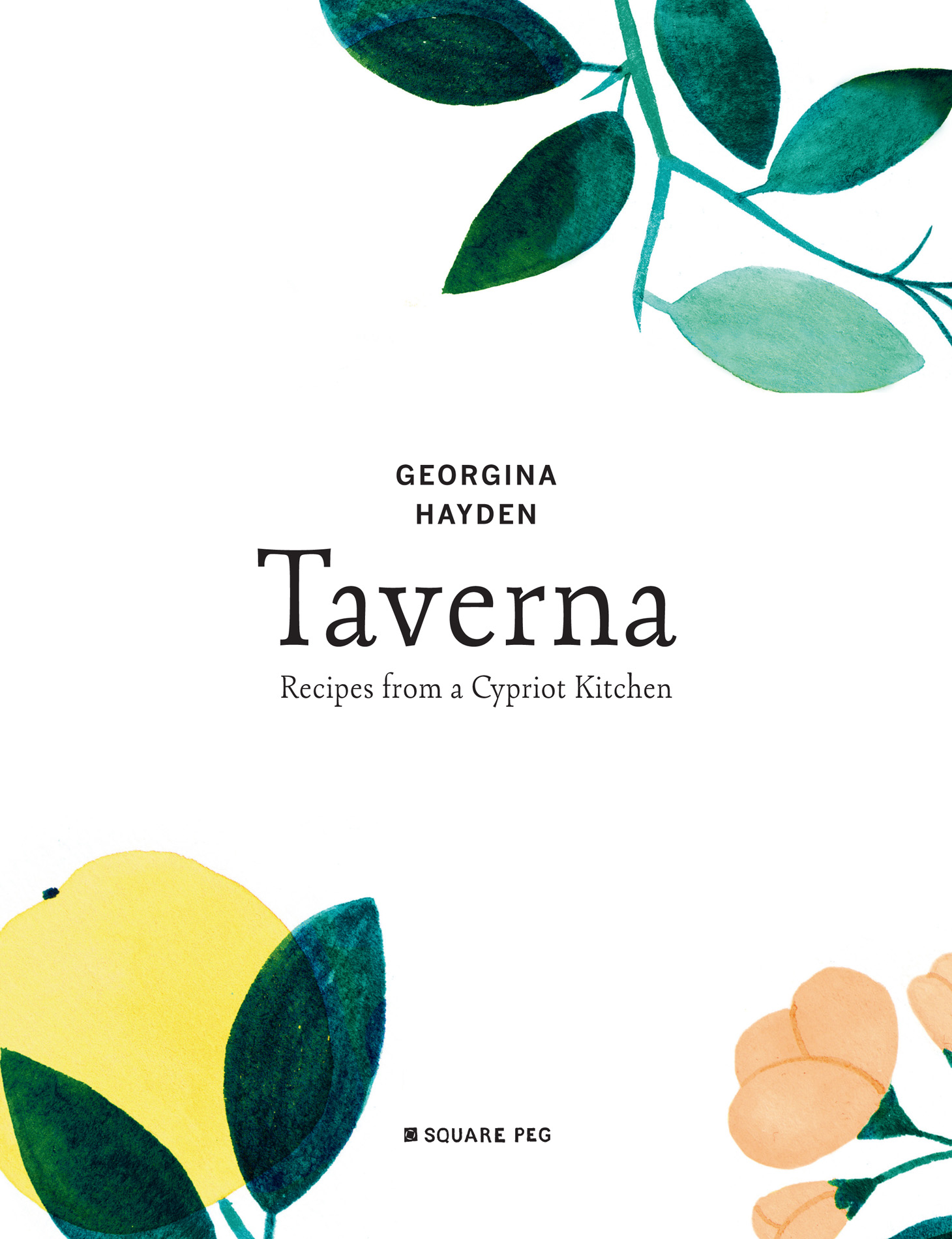

To Bapou Eftihi and Bapou Taki. For coming to England, working hard and shouting about our heritage. And to Yiayia Maroulla and Yiayia Martha. For being the inspiring matriarchs, driving forces, and cooks behind it all.

Introduction

When I was young I would help both my yiayias in the kitchen, absorbing every bit of information I could and hoping their cooking sensibilities would rub off on to me. Shelling broad beans, filling bourekia (sweet ricotta and cinnamon filled pastries), and rolling out hundreds of cheesy flaounes for what felt like the entire Cypriot community are just some of the many food memories of my childhood.

I have collected the recipes and dreamt about this book for as long as I can remember.

Both my grandparents moved to England in the 1950s. My dads parents opened and ran a successful Cypriot taverna in Tufnell Park for almost 30 years: it was the heart of our family and the inspiration behind the title of this book. We all lived in the flats upstairs my grandparents and aunt included and even when my parents, sister Lulu and I moved out we would still spend our weekends there. After Saturday Greek school (my most hated of all days), Lulu and I would run straight to the restaurant and try and help our yiayia set up by laying tables, filling the salt and pepper pots and cleaning. In reality we mostly got under her feet and would be sent upstairs to play instead, or to the back yard. The kitchen was small by restaurant standards today, but big enough for my grandparents to cook everything from scratch. It was a galley style kitchen, with an enormous grill for all the kebabs and meat. My yiayia would work all day making the dips, preparing all the mezedes, slow-cooking stews, stuffing vine leaves and baking trays of sweets. My bapou was obsessive about cleanliness and every piece of crockery, cutlery and glassware was wiped to within an inch of its life. It was a true Mediterranean kitchen vocal, fiery and passionate and everyone wanted to be a part of it. Every holiday or celebration was spent there it was a huge space and big enough for all arms of our sprawling family to be together. New Years Eve was my favourite of these days, as the restaurant would be open for business and heaving with regulars. Us grandkids would be ushered upstairs and kept there until around 11p.m. We would play games and dress up, and then when all the customers had finished their meals we were allowed back downstairs to party. Being small often meant falling asleep under a table or on a chair shortly after midnight, but boy it was worth it.

My mums parents, equally food driven, opened one of the first Cypriot grocers and delis in North London and imported all our traditional ingredients. Customers would come from miles away to shop there. It is hard to imagine now, but items such as halloumi, dried beans, lentils, even olive oil were not commonly found in supermarkets in the 1960s like they are today. They were a formidable pair, whom I miss dearly. My bapou worked insanely hard, starting out with nothing and working all the hours God sent in a Walls sausage factory before opening his first shop. They retired before I was born but I have always enjoyed the stories. The first thing my aunt and my mum mention when talking about the grocers was the smell, how evocative it was. All the produce was in sacks, large barrels, nothing was pre-packaged. Sacks of louvi, fasoles (black-eyed peas and white beans), strings of loukanika and mounds of seasonal fruit, veg and herbs. Huge tubs of different olives, including a special olive from their home village of Lythrodontas, which is famous for its groves. A huge wheel of kefalotyri that would stay out all day and be sold by the slice. Halloumi in brine, boxes of salt cod, fresh bread delivered every day and shelves of baklava, galatoboureko and kataifi. My mum would stand on stacked boxes of Coca Cola cans to reach the scales and weigh up pound bags of all the dry ingredients.

Every Sunday the shop would be shut and my mum would go with my bapou and help clear it out. She was small enough to get into the fridges and climb in and clean them. Once home he would take a long bath, filled with Radox, then drive his much prized Mercedes to Leicester Square for his weekly coffee-shop visit. My yiayia never knew what to expect in the afternoons, as he would often bring back homeless people he had met while out on his errands or drives. His big heart, and poor upbringing, made him empathetic and he would take in anyone he met and bonded with and would feed them. The house was always filled with people and food. Even when we were young, and my grandparents had retired, they still loved visiting Leicester Square and would take us for Chinese coconut buns on Gerrard Street, one of my favourite childhood memories.

Feasting, family and community is not just the bedrock of my family, but of Cypriot culture. Growing up it was so ingrained in our everyday life I almost took it for granted, not fully appreciating that this wasnt everybodys reality. As an adult Ive realised how much this has influenced how I cook. Food is the soundtrack to my family life. Not just for big family events like birthday parties or religious holidays, but also food that captures quieter moods and moments of connection. Like my first book, Stirring Slowly, the recipes in this book reflect all those different moments of life: from meat feasts and mezedes to pared-back vegan weeknight dinners.

Cypriot food has all these bases covered. It is steeped in tradition and rituals. There are foods that heal, like the avgolemoni on . There are also all the incredible influences. With its Greek and Turkish heritage, English rule and Middle Eastern neighbours, Cyprus is a melting point of ingredients, flavours and recipes. On the one hand there are quintessentially Greek aspects like eating a village salad with the sweetest tomatoes and creamiest feta, while looking out on to turquoise sea. On the other hand there is the use of cumin and coriander in our cooking, which are undoubtedly Eastern influences.

One of the first things people ask me when I explain that I am from Cyprus is Greek or Turkish? Although I am Greek Cypriot, this book is completely personal and not political. If anything I am Cypriot first and foremost. Take the iconic recipe: stuffed vine leaves. In Greece they are called dolmathes, in Turkey they are called dolma, in Cyprus they are called koupepia (or as we actually say it, koubebia Cypriots pronounce pi softer than mainland Greeks) and so thats what I call them in this book. Stuffing vine leaves and other veg is an ancient tradition right across Eastern Europe and the Middle East. And my recipe doesnt claim to be definitive these are the recipes I have grown up with. The ones passed down to me from my yiayias, my mum, my aunts, and that I want to pass down also.

At the same time I live a modern life with my own tastes, time pressures and shopping landscape. This book is my take on traditional recipes, some of them straight from my yiayia, others tweaked to make them more accessible and the ingredients more obtainable. Much as I would love to give you my Yiayia Marthas exact recipe for (her addictive) taramosalata, it is near impossible. Hardly anyone would be able to find the roe she uses so I have adapted it so it is as close as can be.

Taverna is a book of memories, appreciation and family. Ive written the intro for this book a thousand times in my heart, and it has been near impossible. Where do I begin? There are so many memories. Youll find countless stories in the intros to the recipes. Almost all of them have a history. I so badly want you to love this as much as I do, and that is the hard part. A lot of this book is laced with nostalgia and emotion; however, I feel confident enough to say that even without the strong memories you will hopefully find a place in your heart and home for the recipes also.

Next page