Case 1.1. Atopic Dermatitis

A 4-year-old child with a known history of moderate atopic dermatitis, allergic rhinitis, and mild asthma returns from weeklong camping trip to the Arizona desert in February. During vacation, family was unable to apply moisturizer daily, but did apply 1% hydrocortisone as recommended on most days. Patient took only one shower during the trip and no baths. The patient did not swim while away. Patients atopic dermatitis flared slightly while on trip, but a few days after return the flare continued and is now out of control 2 weeks later.

She saw her PCP who prescribed a course of oral antibiotics for impetiginized areas, but patient has only improved slightly. Patient currently waking each night to scratch, finding blood on sheets in the morning; weeping patches at ankles, wrists, as well as popliteal fossae and antecubital fossae are persistent and unresponsive to topical steroids and ointment moisturizer. Patient is co-sleeping due to all the discomfort and unable to go to daycare due to itching and the weeping plaques (Fig. ).

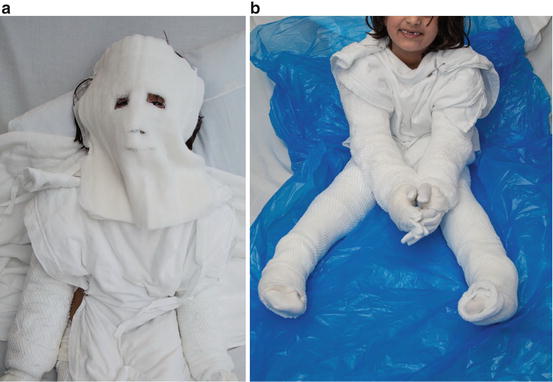

Fig. 1.1

( a ), ( b ). A 4-year-old child with flare of moderate atopic dermatitis

Questions

What, if any, further workup would you perform?

What systemic treatments would you employ for this patient?

What is the role for topical treatment in patients with this severity of atopic dermatitis flare?

Discussion

Atopic dermatitis (AD) is a common chronic inflammatory condition that affects all age groups and disproportionately affects the pediatric population. AD is an issue of paramount importance to clinical practice of pediatricians and dermatologists alike. Pediatric atopic dermatitis can disrupt normal growth and development of affected children, lead to secondary infection, significantly affect the quality of life of families with affected children, and be financially burdensome [].

Treatment of all pediatric atopic dermatitis has five components that must all be addressed simultaneously in order to heal the skin and prevent flares.

Repair the skin barrier

Treat inflammation

Treat superinfections

Identify and remove triggers

Educate the patient and caregivers about the nature of this chronic remitting and relapsing disease

Roles of Topical Treatments: Barrier Repair and Inflammation

Barrier repair is the cornerstone of atopic dermatitis care. When patients leave the hospital, it is critical that they have the tools and understand the importance of maintaining the barrier. In the hospital, this can be well accomplished with moisturizing the skin. In general in dermatology practice, ointments (clear, greasy substances such as white petrolatum) are preferred for sealing moisture into skin. The soak and smear method is commonly employed in outpatient dermatology and can be translated to the hospital setting. The basics are a soak for 1015 min in a comfortable temperature bathtub, then to apply the medicated ointments and then a layer of emollient. The absorption can be increased with occlusion and often putting damp dressings (or pajamas) over the ointments, followed by warm blankets to keep the patient comfortable. At Mayo Clinic, wet dressings have been used for many years for inpatient atopic dermatitis (Fig. ].

Fig. 1.2

( a ), ( b ). A 6-year-old child with atopic dermatitis in wet dressings

Inflammation is a driving force in atopic dermatitis, and providing adequate treatment especially through skin-directed therapy can be challenging at all ages. When patients are hospitalized, demonstrating that skin-directed therapy is safe and effective is important for outpatient success. Topical steroids are the mainstay of treatment of inflammation in atopic dermatitis. In the hospitalized patient, one common challenge is obtaining sufficient quantities for application due to miscommunications between physicians and bedside staff or the pharmacy. The physician must pay close attention to the quantities ordered to ensure sufficient amounts are delivered to the bedside. A helpful trick can be to order a 1-lb (454 g) jar to the bedside for the body application; this should be enough to treat an adult body surface area twice daily for 1 week. In children and infants, these quantities are less (~250 g for a child, ~100 g for an infant) []; however, medications in larger jars are often easier to apply than those in smaller tubes. Medicated ointments or creams should be applied prior to moisturizers to help increase penetration into the skin. The medications are generally felt to be absorbed within 30min.

Roles for Systemic Therapies: Pruritus and Infection

A second key part to barrier repair is to prevent scratching or rubbing, thus bringing mechanical damage to the barrier. The most effective way to do this is to repair the barrier, which improves itch dramatically. Itch is often the most difficult symptom to treat. Use of sedating antihistamines at bedtime to prevent overnight scratching is utilized during acute flares; while these medications do not effectively treat the itch, they are useful in assisting in undisturbed sleep. Daytime non-sedating or lower dose sedating antihistamines are not recommended because they are less effective than direct barrier repair and treatment of the inflammation as the itch is not directly histamine driven []. If the skin is not markedly improved after aggressive topical therapy for 48 h, oral antibiotics may also be added depending on culture results (see below) .

Role of Infection and Further Workup: Surveillance Cultures

In the pediatric patient who has been hospitalized for their atopic dermatitis, infection is a common reason for flare. Infection is most commonly from S. Aureus (MSSA or MRSA), but viral superinfection with HSV (eczema herpeticum) or coxsackie (eczema coxsackium) can also lead to flares. In contrast to the usual teaching in pediatrics, dermatologists will frequently swab areas that do not appear overtly impetiginized for surveillance cultures. This allows therapy to be tailored more accurately if the patient is not improving with barrier repair and treatment of inflammation. Skin infection in atopic patients may require primary treatment with oral antibiotics, specifically an antibiotic that has adequate coverage of Gram-positive bacteria. Should the patient have a history of MRSA, cultures of the skin should be taken and used to tailor therapy. If needed, coverage for MRSA can be utilized; however, it is important to remember that while TMP-Sulfa methoxazole is often used for MRSA, it has less adequate Streptococcal coverage and thus is not generally used first line in these patients.