The fetal myocardium has a distinctive histological appearance that differs from the histological appearance of adult myocardium. Familiarity with these differences is important when examining fetal tissues. In addition, there are specific vascular structures, such as the umbilical vein and ductus arteriosus, that represent components of the fetal circulation and are only normally present during gestation and in the early neonatal period. This chapter highlights the histological features of the fetal and neonatal heart, and some of these unique vascular structures during fetal life.

Embryology

Formation of the human heart is a complex developmental process that is reviewed more extensively in embryology texts []. It is reviewed briefly in this chapter for background purposes and as needed to assist in the understanding of cardiac anatomy and structure of the endocardium, myocardium, and epicardium. The heart begins to form from bilateral angiogenic clusters located in the splanchnic mesoderm of the embryo. These clusters form into the bilateral endocardial tubes that fuse with the folding of the embryo around 21 to 22 days postconception. The developing heart tube is suspended in the pericardial cavity by a dorsal mesocardium and surrounded by two mesodermal layers, the cardiac jelly and the epimyocardial mantle. Cells that invade the cardiac jelly will become the endothelium and the cardiac tube becomes divided into three layers: endocardium, myocardium, and epicardium. The cardiac tube is initially a straight tube with its cranial end attached to the branchial arches. The intrapericardial portion consists of the bulbus cordis and ventricular tissues, and the caudal end, or atrial portion, is embedded in the septum transversum.

As the heart tube elongates, it also bends, a process known as formation of the cardiac loop , which begins on day 23. The cephalic portion of the heart tube moves ventrally, caudally, and to the right while the caudal portion moves dorsally, cranially, and to the left. During this process of looping, which is completed around day 28, the cranial portion of the heart tube gives rise to the truncus arteriosus, the conus cordis, and the trabeculated part of the right ventricle (derived from the bulbus cordis). The ventricular portion of the heart tube gives rise to the primitive left ventricle and the atrial portion of the heart tube becomes incorporated into the pericardium as it takes its dorsal position.

Partitioning of the chambers begins around day 27 postconception. The atrial septum forms from two distinct membranes: septum primum and septum secundum. Septum primum appears first and grows downward toward the endocardial cushions but does not reach the endocardial cushions, leaving an opening known as ostium primum that is later closed by growth of the endocardial cushions. Fenestrations appear in the upper portion of septum primum. These openings coalesce and form an opening known as ostium secundum . Subsequently, septum secundum, the second interatrial membrane, begins to form to the right of septum primum. It is an incomplete septum with the upper solid portion overlapping the ostium secundum and a more inferior ovoid defect known as foramen ovale. Therefore, shunting blood from the right atrium occurs across the interatrial septum through the foramen ovale, over the free edge of septum primum, and into the left atrium.

The common atrioventricular canal, which encompasses the lower atrial and upper ventricular portions in the center of the heart, is closed by formation of the lateral, superior, and inferior endocardial cushions that appear as bulges of myocardium and fuse to form two separate left and right atrioventricular canals. The majority of the ventricular septum is formed while the two primitive ventricles are enlarging. The medial walls of the two enlarging ventricles fuse and form a nearly complete interventricular septum with a small opening just inferior to the endocardial cushions. This opening persists until conal septal formation is complete and the upper portion of the ventricular septum, also known as the membranous septum , is closed by the union of portions of the right and left conal swellings and the inferior atrioventricular cushion.

The outflow of the ventricles is created by the formation of the conal swellings within the conus cordis and the truncal swellings within the truncus arteriosus. The truncal swellings appear in about the fifth week postconception as ridges that form from the right superior and left inferior truncal walls. These ridges grow toward each other and twist around one another, creating the spiral aorticopulmonary septum. Within the more proximal cordis conus, similar bilateral swellings appear and grow upward, meeting the aorticopulmonary septum. The conal swellings also fuse with the inferior atrioventricular cushion to close the upper portion of the interventricular septum.

Histology

The low-power appearance of the fetal and neonatal myocardium is quite different from the appearance of adult myocardium. The striking difference is the cellularity of the myocardium ( see Fig. ]. Nevertheless, the highly cellular appearance of the fetal myocardium is not maintained throughout life.

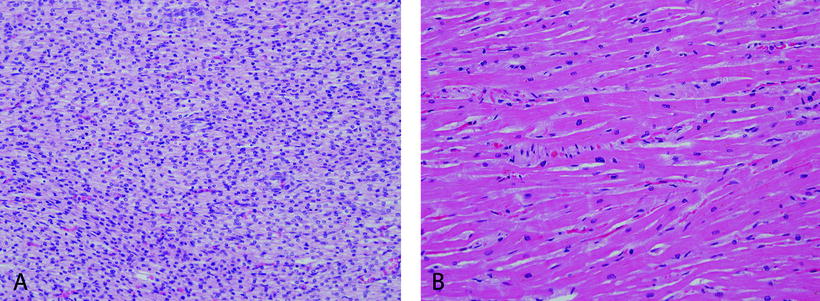

Figure 1-1.

Comparison of fetal and adult myocardium. A , Fetal myocardium at 23 weeks gestation and B , adult myocardium is shown. Note the marked hypercellularity and higher nuclear to cytoplasmic ratio of the fetal myocardium compared with the adult myocardium. (Hematoxylin and eosin [H&E], 20.)

Despite these morphologic cellular differences, the basic histological structure of the fetal heart is not different from the adult heart. The majority of the heart consists of three principle layers: epicardium, myocardium, and endocardium. Additionally, there are specialized tissues such as the fibrous skeleton, valves, and conduction system that can be examined if they are specifically sampled for histological study.

Pericardium

The heart is surrounded by a fibrous sac, the pericardium (parietal pericardium), which grossly is a thin membrane in the fetus. Anatomically, the parietal pericardium is in continuity with the serous (visceral) pericardium, also known as the epicardium, at the pericardial reflections over the great vessels [].

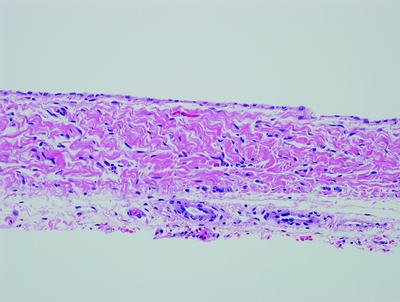

Figure 1-2.

Fetal pericardium at 23 weeks gestation. The fetal pericardium is a delicate, membranous structure with a simple squamous epithelium and a layer of underlying dense connective tissue. In the adult, the loose connective tissue outside the pericardium can contain adipose tissue, but there is usually little adipose tissue in the fetus. (H&E, 20.)