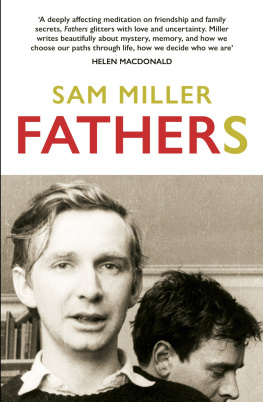

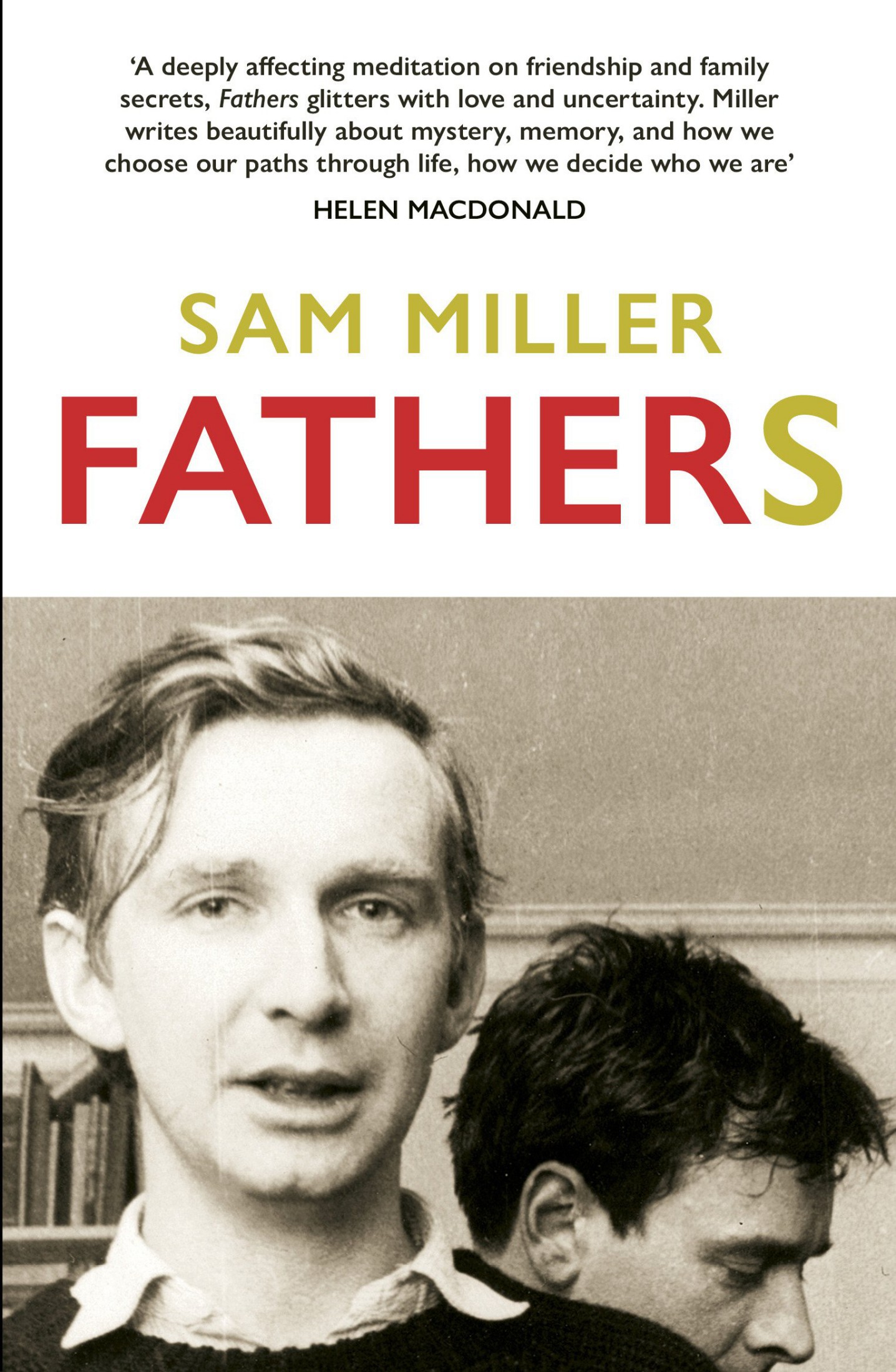

Sam Miller - Fathers

Here you can read online Sam Miller - Fathers full text of the book (entire story) in english for free. Download pdf and epub, get meaning, cover and reviews about this ebook. year: 2018, publisher: Penguin Random House, genre: Home and family. Description of the work, (preface) as well as reviews are available. Best literature library LitArk.com created for fans of good reading and offers a wide selection of genres:

Romance novel

Science fiction

Adventure

Detective

Science

History

Home and family

Prose

Art

Politics

Computer

Non-fiction

Religion

Business

Children

Humor

Choose a favorite category and find really read worthwhile books. Enjoy immersion in the world of imagination, feel the emotions of the characters or learn something new for yourself, make an fascinating discovery.

- Book:Fathers

- Author:

- Publisher:Penguin Random House

- Genre:

- Year:2018

- Rating:5 / 5

- Favourites:Add to favourites

- Your mark:

- 100

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Fathers: summary, description and annotation

We offer to read an annotation, description, summary or preface (depends on what the author of the book "Fathers" wrote himself). If you haven't found the necessary information about the book — write in the comments, we will try to find it.

Fathers — read online for free the complete book (whole text) full work

Below is the text of the book, divided by pages. System saving the place of the last page read, allows you to conveniently read the book "Fathers" online for free, without having to search again every time where you left off. Put a bookmark, and you can go to the page where you finished reading at any time.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

In early 2014, after many years living abroad, Sam Miller returned to his childhood home in London. His father was dying.

When the editor, writer, critic and academic Karl Miller died later that year, the obituaries spoke of his brilliance and influence, of how he founded the London Review of Books, and how he had shaped the careers of some of the finest writers and poets of the second half of the twentieth century. But they gave little sense of Karl Miller beyond the world of work: the warm, funny, football-loving family man so adored by his children and grandchildren.

In the months after his death, Sam began to write about his father. He had been told, long ago, a family secret involving his parents and a close friend. Now, by reading his fathers papers and with the help of his mother, he was able to piece together a remarkable story.

Fathers is the result: a tender, thoughtful exploration of childhood and parenthood, of friendship, love and loyalty.

Sam Miller was born and brought up in London, but has spent much of his adult life in India. He is a former BBC journalist and is the author of Delhi: Adventures in a Megacity (2009), Blue Guide: India (2012) and A Strange Kind of Paradise: India Through Foreign Eyes (2014). He is also the translator of The Marvellous (But Authentic) Adventures of Captain Corcoran (2016) by Alfred Assollant.

Non-fiction

Delhi: Adventures in a Megacity

Blue Guide: India

A Strange Kind of Paradise: India Through Foreign Eyes

Translation

The Marvellous (but Authentic) Adventures of Captain Corcoran by Alfred Assollant

For my parents

On the 24th of September 2014, shortly after eating his customary lunch hummus on toast, some prawns and a few grapes my father headed upstairs to his bedroom. Halfway up the first flight, he fell backwards, crashing into a wooden dresser stacked with crockery, and onto the terracotta-tiled floor of the basement of the house in which he had lived for more than half a century. One blue fur-lined slipper remained on the step from which hed fallen. He died two hours later. I was not there.

My father had been ill for a long time. Very ill, at times. And that, for a hypochondriac, is a most shocking thing. But he had recovered, and I felt able to go away, to return briefly to India, where I had lived for more than a decade foolishly convinced that my father would be there on my return to London.

He never liked it when I went away, or that I had lived for so many years in what he referred to as foreign parts. He would invariably tell me whenever I left London that the next time I saw him he would be in a box. And, he would always add, then youll be sorry. I might have interpreted this as an attempt to make me feel guilty, or to induce pity. But to me it had become neither of these things. These words were always delivered with a roguish look upon his face. And they became his circumlocutory way of saying how much he missed me; a piece of repeated nostalgia, a self-quotation; a turn of phrase he always used, and always would use, until the day he died. It was something that I told my friends, as a way of describing my fathers uncommon sense of humour and they didnt always get the joke. For this was gentle teasing on the part of a literary hypochondriac, the same man who had written, a good fifteen years before he actually died, this autobiographical couplet:

No poor soul was ever iller

than Karl Fergus Connor Miller

In fact, I almost was with my father when he died. We had spent many of his last days together. I had returned to stay in the old family home in London six months before his death, the same house in which I had been born, fifty-two years earlier. Soon after I returned, a doctor, a consultant in palliative care, came round to the house and said that he had only weeks to live. He survived that first set of weeks and she came round again, and said he still had only weeks to live. And, stubborn to the end, once more he proved her prophecy wrong.

I had not returned to London out of some sense of filial guilt or duty, but out of a selfish longing to be with this man who had done so much to shape me, whose jokes became my jokes, who had edited almost every word I had ever written. I would try, and this too may have been selfish on my part, to do all that I could to keep him alive and to do all that I could to make him laugh. And he surprised us all family, friends and doctors by emerging from the fog of near-death to shine and sparkle once again; still a sick man, but one who remained entirely and indubitably the person I had known all my life. His wit was undimmed, and so was his capacity for affection.

He died on a Wednesday. I had returned to Delhi on the Tuesday to be reunited with a former girlfriend. He spoke to me on the phone on the morning of his death: sweet, warming words, and then he sang to me, as if he knew he was saying goodbye, and wanted to leave me with a happy final memory. When he fell down those stairs two hours later, my mother called me, and there was nothing I could do or she, or anyone else. An ambulance came and my father was carried to his room. He never regained consciousness and died with the rest of the family at his bedside. I was there, vicariously, at the end of a phone, listening to small cries of anguish from my mother unable to be quite sure what was happening.

After he died, my sister spoke to me, and told me he would still be there, his body at least, in his bedroom, when I returned the next morning from India. She knew, I think, how much I wanted to see him; how upset I was by his death, and by my absence at the time of his death. But when I arrived, full of desolate expectation and brimming with unspoken words, his bed lay empty; his room had been tidied, fresh air was sweeping through the open window. He had gone. My father had been taken away, at the insistence of the police. A post-mortem was necessary and so he was locked up in a mortuary cold store, one of many cadavers. I was distraught. On the long and lonely flight back from Delhi, I had prepared many things that I wanted to say to my father.

My brother rang the mortuary on my behalf, and, after some wrangling, they said that I could see my father, but only for five minutes, and there would be a glass window separating us. At first, I said I would go. And then I shivered as I imagined him cold, naked, or covered with a white sheet, laid out on a slab. I chose not to see him in the mortuary.

That weekend, I wrote a short story, a true tale, for myself and for my children. It described and gave context to those last words, words of song, that I would hear from my father, down a phone line to India. Its a brief story about his life and mine that I would later read out at his funeral:

I was not a fussy child. I ate almost everything, I had no interest in clothes, and did not care for special blankets or teddies. But I could not bear having my hair cut. It seemed like the most terrible indignity, an assault on my person and identity. It was an embarrassment almost as bad as being seen naked in public. On one occasion, a short back and sides left me with the humiliation of two large tufts of upward-pointing hair. My father tried to cheer me up. I was inconsolable. I look like Rufty Tufty, I exclaimed through my tears, a reference to a long-forgotten cartoon squirrel who starred in road-safety films of the late 1960s.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

Similar books «Fathers»

Look at similar books to Fathers. We have selected literature similar in name and meaning in the hope of providing readers with more options to find new, interesting, not yet read works.

Discussion, reviews of the book Fathers and just readers' own opinions. Leave your comments, write what you think about the work, its meaning or the main characters. Specify what exactly you liked and what you didn't like, and why you think so.