Copyright 1998 by Eric Ripert and Maguy Le Coze.

All rights reserved.

Published in the United States by Clarkson Potter/Publishers, an imprint of the Crown Publishing Group, a division of Random House LLC, a Penguin Random House Company, New York.

CLARKSON POTTER is a trademark and POTTER with colophon is a registered trademark of Random House LLC.

Originally published in the United States by Clarkson Potter/Publishers, an imprint of the Crown Publishing Group, a division of Random House LLC, New York, in 1998.

T O MY TRUE FRIEND, GILBERT

Eric

T O GILBERT, MY BELOVED BROTHER

Maguy

A CKNOWLEDGMENTS

I never thought it would take twenty-five years to give birth but thats the way it happened. My brother, Gilbert, who never procrastinated, curiously did so with this book. So Eric and I decided that we had to finish this long-lasting project.

We would like to thank, for their collaboration, Lee Ann Cox, for testing and writing recipes; Eileen Daspin, for struggling through our terrible English; Franois Portman, who traveled to freezing Maine for the perfect photographs; Herve Poussot; Christopher Muller, our sous chef; and the entire team at Le Bernardin.

C ONTENTS

I NTRODUCTION

I ve heard everyone claiming we were this close and flashing up two fingers held together to describe a special friendship.

My brother, Gilbert, and I were even closer, and I cannot think of a better story than this one to demonstrate our closeness. On a summer night a few years ago, we were on vacation in Port Navalo, the tiny village in Brittany where we grew up. Wed been drinking at our favorite hangout, Le Cherokee, with a group of friends. At 2 A.M . we decided to move on to another club. We all piled into our respective cars and headed out, one after the other. Gilbert and I were fifth in line.

We were still fifth two minutes later when a policeman noticed our group weaving. He stopped us with a peep of a siren and a show of his hand. As he began a slow, car-by-car DWI check, I saw Gilbert stiffen nervously. But at the same time, I noticed a twinkle in his eyes and I knew he had something in mind.

Soufflez. Blow, the policeman ordered, thrusting a balloon through the window.

It was the French version of a Breathalyzer test, and would have worked for most people. But as soon as the policeman turned his back, Gilbert passed the balloon to me. He was well over the limit with Cognac; I had only been drinking Champagne. Maguy, he insisted, I cannot do it, just do it for me. And in an instant, I had filled the balloon, returned it to Gilbert, who handed it off as his own. We were waved on.

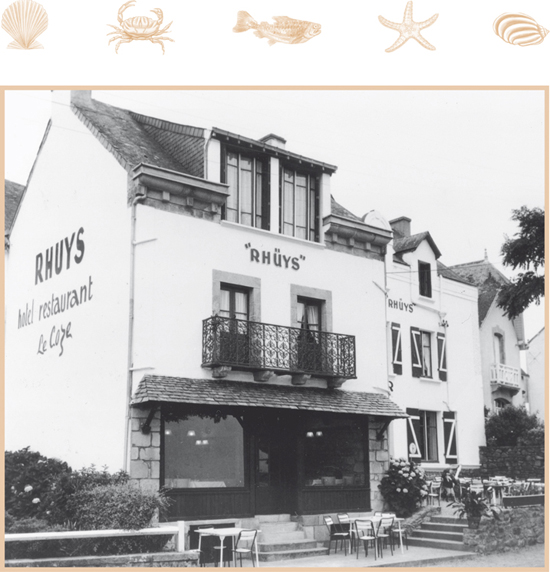

The Htel du Rhuys.

Gilbert and me, ages five and six. We were always inseparable.

That closeness, that shared breath, is the heart and soul of Le Bernardin. Its the foundation of a story that starts with us, Gilbert and Maguy Le Coze, two French halves of a whole who made a life together. Gilbert was the most important person in my life, and I in his. We had a bond that for some was incomprehensible, of blood and more than blood. For us, it was always natural. We came into the world separately, first me, then Gilbert, but we were barely a beat apart.

Now that hes gone, I feel it even more. I find myself using his words, his gestures. I see him in me. I open my mouth and out comes Gilbert. I look at old photos of us, side by side, and see how we both lean the same way, tilt our heads, exist in the moment together. At night in bed, I talk to him, and he talks back.

It was always that way, from the beginning. We had our own secret world, a world that opened up when Gilbert was born, eighteen months after me, in Port Navalo. He is in my earliest memories. I remember my mother large with him. I remember holding him, feeding him, watching him. Once, when he was just three, I dropped him on his head, and I couldnt bear the thought that if he died, I would die too.

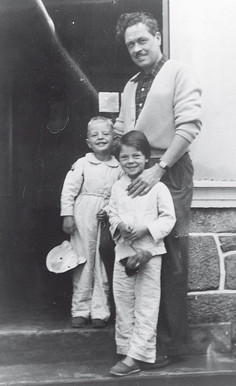

Gilbert and me with Papa. We were about three and four, and the masks were for Mardi Gras.

Between Gilbert and me there was no space, and we wanted it that way. It was because of our childhood, which was filled not only with bikes and puppies, secret forts and scabbed knees, but with hard work that reflected the lives of our parents. That meant helping run the Htel du Rhuys, the small inn and restaurant Maman and Papa bought when they married. The work we all did was hardthe kind that makes you tired, achy, and old. As a girl, I often cried to myself that we were born to do choresscrub, scour, and clean. But on many days those tears turned to smiles.

The two of us with a cousin at the beach.

Only with Gilbert did I feel girlish and carefree. I can see him now, so smooth-faced, a sweetly wicked French schoolboy, who hated to conform to the disciplines of schooling. Even at an early age, he wanted to do things his own way. In public, we were obedient little people, doing what our parents said, but left alone, we would plan and plot. To retaliate, wed sneak upstairs with a tray of shrimp and a bottle of cider, and eat until we were sick. Behind Papas back in the kitchen, wed snatch handfuls of freshly fried potato chips, then quickly lick our fingers to conceal the crime. We had secret games and hiding places, we made plans to break out of Port Navalo.