Lost Letters of Medieval Life

Lost Letters of Medieval Life

English Society, 12001250

EDITED AND TRANSLATED BY

Martha Carlin and David Crouch

University of Pennsylvania Press

Philadelphia

THE MIDDLE AGES SERIES

Ruth Mazo Karras, Series Editor

Edward Peters, Founding Editor

A complete list of books in the series is available from the publisher.

Copyright 2013 University of Pennsylvania Press

All rights reserved. Except for brief quotations used for purposes of review or scholarly citation,

none of this book may be reproduced in any form by any means without written permission

from the publisher.

Published by

University of Pennsylvania Press

Philadelphia, Pennsylvania 19104-4112

www.upenn.edu/pennpress

Printed in the United States of America on acid-free paper

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Lost letters of medieval life : English society, 1200-1250 / edited and translated by Martha Carlin and David Crouch.

p. cm. (The Middle Ages series)

Includes bibliographical references and indexes.

ISBN: 978-0-8122-4459-5 (hardcover : alk. paper)

1. EnglandCivilization1066-1485Sources. 2. Letter writingEarly works to 1800.

3. EnglandSocial life and customs10661485Sources. I. Carlin, Martha. II. David

Crouch. III. Series: The Middle Ages series.

DA170 .L67 2013

942.034

2012023969

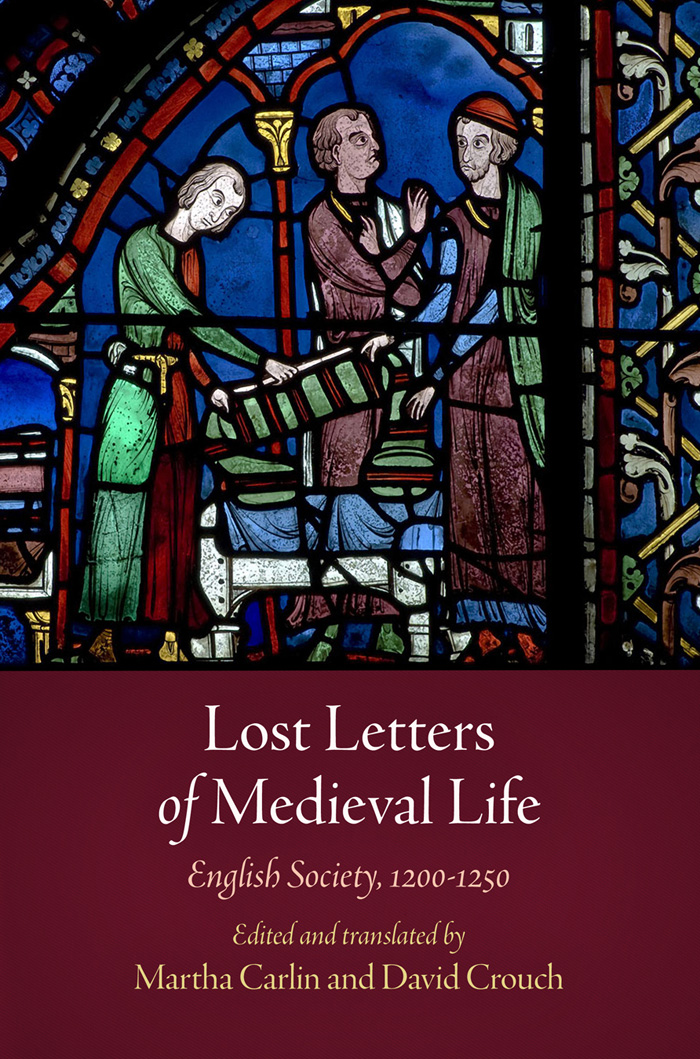

Frontispiece: Bodleian Library, Oxford, Fairfax MS 27, fol. 4v. The four texts that begin with a C are D OCUMENTS 6568; the two texts that begin with a B are D OCUMENT 61 and the beginning of D OCUMENT 62.

CONTENTS

ILLUSTRATIONS

PREFACE

In 1847 the English antiquary Thomas Hudson Turner published a brief note about a manuscript that recently had come to his notice, and which contained a collection of model business correspondence. Turner included tantalizing transcriptions of three letters, all in Latin, between an earl and the merchants who supplied him with wine, cloth, and furs. However, other than saying that the collection dated from the reign of Henry III (121672), he provided no detailed description of its contents and no means of identifying the manuscript itself. But such as it was, this was the first printed notice of the work that provides the bulk of the documents in this collection.

Intrigued by Turners extracts from the business correspondence, of which few examples survive from thirteenth-century England, Martha Carlin searched for the manuscript and located it at last in the British Library, where it formed one section (Article 5, folios 88133) of a larger volume, Additional MS 8167 (hereafter Add. 8167). Turners letters proved to be drawn from a formulary, a collection of model correspondence designed for the instruction of business students.

Although Turners article of 1847 seems to have escaped later scholarly notice, a number of scholars since his day have also noted the existence of the formulary material in Add. 8167. In 1879 Georg Waitz printed a description of urban trades and crafts that occurs on folios 88r90v but did not discuss the other contents of Article 5 or of the manuscript more generally. Waitz also mistakenly identified the manuscript as dating from the fourteenth century. Each of these scholars, however, focused on individual elements of the formulary; none of them remarked on the extraordinary range of the documents themselves or their significance as a collection.

As our study of the documents expanded we discovered that, despite Richardsons belief that Add. 8167 was the oldest English formulary, several other collections (discussed below) were even earlier. A particularly rich and important one is in the Bodleian Library, where it forms part of Fairfax MS 27 (hereafter Fairfax 27). As we planned out the project that has become this book, it was clear that the letters in Fairfax 27 form a significant complement to the material in Add. 8167. This book therefore is a selection of letters and other documents drawn from these two early thirteenth-century formularies. They allow us to rediscover a lost medieval world through the model documents they preserve, which represent whole classes of genuine letters and other material that have not survived to the present day because they were discarded as of no lasting importance. Luckily, we can infer their existence and character from these surviving exemplars. It has to be said that the selection of material was the easy part. One reason why this is the first serious study of these documents is they are by no means easy to read. Many of them were ineptly drafted, and clumsily transcribed and altered by the medieval copyists, a not unusual feature in what were classroom products. Recovering their sense was frequently a frustrating task, but the importance of the material meant that it was a worthwhile and necessary endeavor.

NOTES

Thomas Hudson Turner, Original Documents, Archaeological Journal, 4 (1847), 14244.

Georg Waitz, Neues Archiv, 4 (1879), 33943. Martha Carlin has printed a corrected transcription and a translation of this text in Shops and Shopping in the Early Thirteenth Century: Three Texts, in Money, Markets and Trade in Late Medieval Europe: Essays in Honour of John H. A. Munro, ed. Lawrin Armstrong, Ivana Elbl, and Martin M. Elbl (Leiden: Brill, 2007), 491537.

Charles Homer Haskins, The Life of Medieval Students as Illustrated by Their Letters, American Historical Review, 3, no. 2 (January 1898), 210, n. 2; rpt. in idem, Studies in Mediaeval Culture (New York: Oxford University Press, 1929), 10. This letter is D OCUMENT 81 in our collection.

See Nol Denholm-Young, Robert Carpenter and the Provisions of Westminster, English Historical Review, 50 (1935), 2235, rpt. in idem, Collected Papers on Mediaeval Subjects (Oxford: Basil Blackwell, 1946), 96110; and again in idem, Collected Papers (Cardiff: University of Wales Press, 1969), 17386. See also idem, Seignorial Adminstration in England (London: Oxford University Press, 1937), 12122.

Henry Gerald Richardson, An Oxford Teacher of the Fifteenth Century, Bulletin of the John Rylands Library, 23, no. 2 (1939), 44750. See also Henry Gerald Richardson, The Oxford Law School Under John, Law Quarterly Review, 57 (1941), 31938; and Henry Gerald Richardson and George Osborne Sayles, Early Coronation Records [Part I], Bulletin of the Institute of Historical Research, 13 (193536), 13438.

Dorothea Oschinsky, Medieval Treatises on Estate Accounting, Economic History Review, 17, no. 1 (1947), 54, 58; eadem, Walter of Henley and Other Treatises on Estate Management and Accounting (Oxford: Clarendon, 1971), 16, 226, 235.

Martin Camargo, The English Manuscripts of Bernard of Meungs Flores Dictaminum, Viator, 12 (1981), 197219 (especially 2048).