Contents

Guide

The author and publisher have provided this e-book to you for your personal use only. You may not make this e-book publicly available in any way. Copyright infringement is against the law. If you believe the copy of this e-book you are reading infringes on the authors copyright, please notify the publisher at: us.macmillanusa.com/piracy.

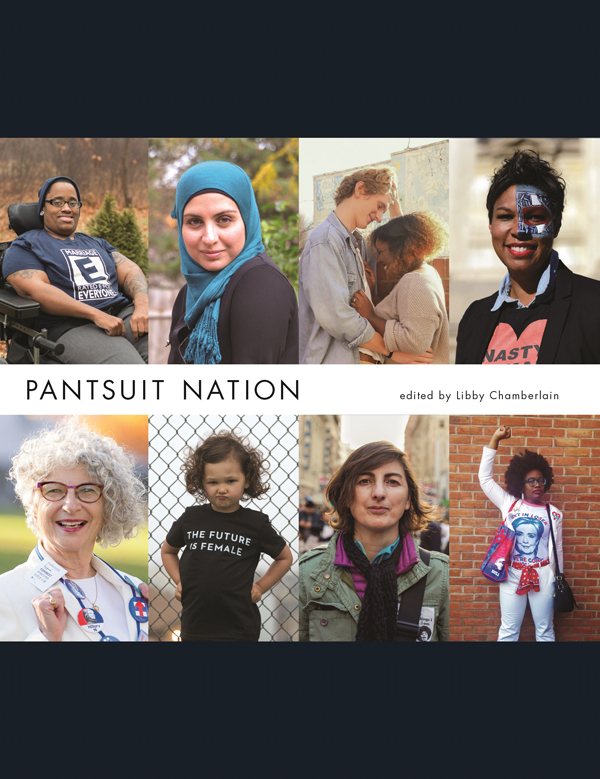

To Pantsuit Nation Glimmers in the dark

The book you are holding in your hands is a time capsule. Its also an experiment in the power of collective storytelling. And its a rallying cry. It grew out of something as improbable and ephemeral as a secret Facebook group for thirty friends who were planning to wear pantsuits to the polls on November 8, 2016. What it becomes next is up to you.

Pantsuit Nation began on October 20, the day after the third presidential debate. Craving an online space that was free of vitriol, fake news, and the abusive commentary that had become commonplace over the course of the 2016 election, I uploaded a photo of Hillary Clinton, radiant in her white pantsuit from the night before, and wrote the following description for the group: Wear a pantsuit on November 8you know why.

The idea to wear a pantsuit to the polls was inspired by a conversation with my friend, Caddie. While watching the debate, Caddie overheard a young woman say something along the lines of Ugh. Another ugly pantsuit. It was less than two weeks after a video had surfaced of the Republican nominee bragging about sexual assault, and yet the conversation turned, as it had so often in the months leading up to that debate, to Secretary Clintons clothing. The volume of her voice. Whether she was smiling not enough or too much. The height of her heels and the cut of her jacket.

I didnt own a pantsuit at the time. It didnt matter. I knew that more than any other campaign pin, slogan, or logo, the pantsuit symbolized this moment in history, and I wanted to wear that symbolto embrace it and embody it and celebrate itwhen I went to cast my vote in that historic election. It turns out I wasnt the only one.

Within one day of creating the group and inviting a handful of my own friends to join, it exploded to more than 24,000 members. Friends invited friends by the thousands to a secret group where they could unabashedly support Secretary Clinton. Where they didnt have to hide their excitement or temper their enthusiasm. Ive found my people! and I knew you were all out there somewhere! were familiar refrains in the group in those first few days. There were few rules, but there was one I was adamant about: in the words of Michelle Obama, we would Go high. Posts that disparaged either candidate or their supporters would not be tolerated. There was plenty of that in other spaces and I wanted to create something different.

While there were a number of memes and pro-Clinton articles being shared in the beginning, something else started happening as well. Members, particularly women, began sharing stories about what this election meant to them. Stories about workplace harassment, about mothers and grandmothers with great aspirations and far-reaching ambitions who were limited not by their creativity or talent but by their gender. Lawyers and teachers and scientists posted in the group about the fight to wear pants, literally, and about the fight for what the pantsuit represented to them: equality, empowerment, and autonomy.

We read about Hank, a TWA stewardess (as they were then called) who attended Stanford Medical School in 1938 and gave up a career in medicine to get married, only to find herself stationed at Pearl Harbor with a six-month-old baby on December 7, 1941. Her granddaughter, Susan (), dedicated her vote for Secretary Clinton to four generations of women in her family, starting with Hank and ending with her own daughter.

Sian () also posted about her grandmother, who raised four children in a tiny apartment in Shanghai before immigrating to the United States. In 2001, standing at her kitchen window in New York Citys Chinatown, she watched the World Trade Center fall and then draped their apartment in American flags and memorabilia, much like the rest of the citys residents.

These stories, which were posted in the group by the hundreds and then by the thousands, were deeply personal and yet profoundly universal. They seemed, at times, to have a generative power of their ownthe more people shared, the more others were inspired to do the same, so that stories begat stories. This was the first glimpse I had of collective storytelling, where the impact of hundreds of thousands and then millions of people gathering together in a virtual space to speak and listen was something unique and worth preserving.

Leading up to the election, the size of the group swelled to 100,000, then to 250,000, and then surpassed 1,000,000 members on November 5. The stories grew, too, not just in number but in scope. We heard from first-generation Americans, from people of color, from immigrants and refugees, from people with disabilities, and from members of the LGBTQIA community about how, for them, the outcome of this election could mean the difference between acceptance and rejection based on their identity, their families, their ancestry, whom they loved, and how they worshipped. The pantsuit, it turns out, could represent everything from a doctors scrubs to a military uniform to a hijab.

Hundreds of thousands and then millions of people gathering together in a virtual space to speak and listen was something unique and worth preserving.

We read Ileanas story () wrote about being a sexual assault survivor and voting for my daughters and yours. There was a rising chorus of voices, beautiful and complex in their differences, but also inspiring in their shared commitment to love, kindness, and inclusion.

Pantsuit Nation was also a catalyst for action. With help from a growing team of volunteers (many of whom simply sent me a brief message asking, Can I help? to which I almost always responded, Yes, please!), we organized a fund-raising drive for the Clinton campaign, which raised more than $200,000 in a matter of days. We set up a call team for phone banking, which was ranked in the top ten nationally on the weekend before the election. Members posted about canvassing and texting undecided voters and volunteering to drive elderly neighbors to their polling locations, often crediting the stories within the group for providing them the motivation they needed to put in those long hours.

The storytellers in our midst, whose voices thrum against the tides of injustice, are our most powerful agents of change.