HOUSES

MADE

OF

WOOD

AND

LIGHT

ROGER FULLINGTON SERIES IN ARCHITECTURE

HOUSES

MADE

OF

WOOD

AND

LIGHT

THE LIFE AND ARCHITECTURE OF HANK SCHUBART

BY MICHELE DUNKERLEY

WITH JANE HICKIE

PHOTOGRAPHS BY JIM ALINDER

UNIVERSITY OF TEXAS PRESS, AUSTIN

Publication of this book was made possible in part by support from Roger Fullington and a challenge grant from the National Endowment for the Humanities.

Text copyright 2012 by Michele Dunkerley

Photographs copyright 2012 by Jim Alinder

All rights reserved | Printed in China | First edition, 2012

Requests for permission to reproduce material from this work should be sent to:

Permissions

University of Texas Press

P.O. Box 7819

Austin, TX 78713-7819

www.utexas.edu/utpress/about/bpermission.html

The paper used in this book meets the minimum requirements of ANSI/NISO Z39.48-1992 (R1997) (Permanence of Paper).

Designed by Lindsay Starr

LIBRARY OF CONGRESS CATALOGING-IN-PUBLICATION DATA

Dunkerley, Michele, 1958

Houses made of wood and light: the life and architecture of Hank Schubart / by Michele Dunkerley with Jane Hickie; photos by Jim Alinder. 1st ed.

p. cm. (Roger Fullington series in architecture)

Includes bibliographical references.

ISBN 978-0-292-72942-1 (cloth : alk. paper) ISBN 978-0-292-73714-3 (e-book)

1. Schubart, Hank, 19161998. 2. ArchitectsUnited StatesBiography. 3. Architecture, DomesticBritish ColumbiaSaltspring IslandHistory20th century. I. Schubart, Hank, 19161998. II. Hickie, Jane. III. Alinder, James. IV. Title. V. Title: Life and architecture of Hank Schubart.

NA737.S3555D86 2012

720.92dc23 [B] 2011038592

ISBN 978-0-292-74268-0 (individual e-book)

For Jane, for helping me find my way to

Salt Spring Island and other open horizons

CONTENTS

FOREWORD

TO OBSERVE THE COLLECTED WORK of Hank Schubart is in no small part to witness the thoughtful expression of locale. The topography of Salt Spring Island itself provides an insistent theme and provides measure to the houses and their sitings. Insofar as each of Schubarts houses responds directly to its conditions of locale, the collective identity of the work offers compelling testimony to architectures ability to be infused by a broad sense of place. In this respect, we might think of the designs as qualifying the inherited experience of landscape as it is made habitable and rendered for us as home.

In a place such as Salt Spring Island, homes declare their preoccupation with issues of terrain and orientation, yet this urge often presents curious contradictions. The direction of the most extravagant ocean views may also be the source of the most extravagant winter stormsthe desire for view might well be at odds with the need for the light and warmth of the sun, and the desire for proximity to the ocean may result in the need for precipitous structural foundations. It is precisely in the reconciliation of such contradictory facts that Schubarts most demonstrable design strength lies, and it is in the houses common sense of ease that his success is so clearly demonstrated.

DESIGN TACTICS

In their special regard for the attributes of Salt Spring settings, Schubarts houses exhibit a number of specific architectural tactics.

First, there is the consistent development of a skewed and room-deep plan-form, most generally lodged in parallel with the natural contours of the site and acknowledging specific visual attributes of both local and distant landscapes. These sometimes extremely narrow configurations promote cross-ventilation, establish that most fundamental necessity of creating level ground, and register the relatively short structural spans of conventional wood framing. Even more significantly, these attenuated interior spaces serve as a kind of spatial lens through which the broader landscape can be observed.

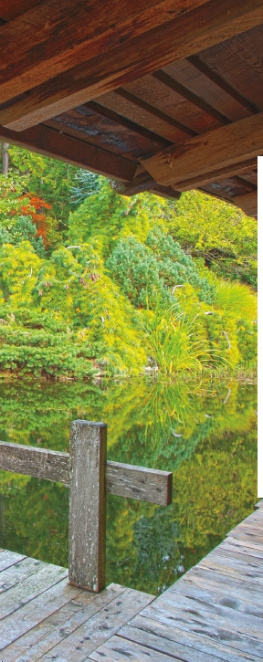

Gold house, interior living room.

Southend house, exterior and pool.

Gordon-Sumpton house, courtyard entrance.

The Gold house offers an especially vivid instance of this approach. Approached from an upper-level access road, the roof itself contributes to the primary presentation of the house, granting virtually no awareness of the adjacent waterfront. The rugged forest terrain is drawn into submission, sheltered under deep, projecting eaves. From this point of arrival, entry to the house immediately provides a deliberately framed view of the ocean landscape beyond, relieving the relatively dark and contained space of the forest and reconciling the houses undulating geometric order with the clear mandate of prospect.

Given the local topography and the compelling desire for a house whose experience culminates in a dramatic view, a narrow and meandering Schubart house almost inevitably results in conditions in which the front and back of the house enjoy radically different prospects. Typically entered through a carefully orchestrated sequence of pathways from higher ground, such a house might confront a steep rock outcrop on its entry side while enjoying a vertiginous drop to the shorefront and ocean only a rooms depth away. In additionand notwithstanding the houses general narrownessthe woodland shade on its perimeter encourages the inclusion of skylit interior spaces that are open to the sky, a feature especially welcome during the often overcast winter days.

In the Southend house, an uphill landscape has been orchestrated in which a necessarily narrow pool and surrounding wooden deck are dramatically poised between the house and an outcrop of rock and arbutus trees. This kind of landscape is often coordinated with the passage from forest to interior, providing a sheltered local ecology that might vary dramatically from the exposed elevations facing the water. An excellent example of this is in the case of the Gordon-Sumpton house, where a carefully scaled outdoor living room enjoys a protected southern aspect clearly distinguished from its surroundings.

While these often dramatic juxtapositions of domestic interiors and the extreme geography of their surroundings occur across the collected works of Schubart, his designs almost always take care to draw the interior realm out into adjacent landscape spaces. Enclosed courtyards and, especially, elevated decks extend the utility of interiors but also mitigate the extreme shift in scale between domestic furnishings and the extraordinary natural surroundings. More specifically, these external spaces often acknowledge very specific conditions of orientation and terrainan unusual rock outcrop or a distinguished tree, for instance. The courtyard that serves as a threshold of arrival also serves as an outdoor living space, bathed in afternoon light and protected from the vigorous and bracing breezes off the water. Similarly but more reservedly, his work uses the extension of primary roof forms to offer both literal and conceptual shelter on arrival.

Next page