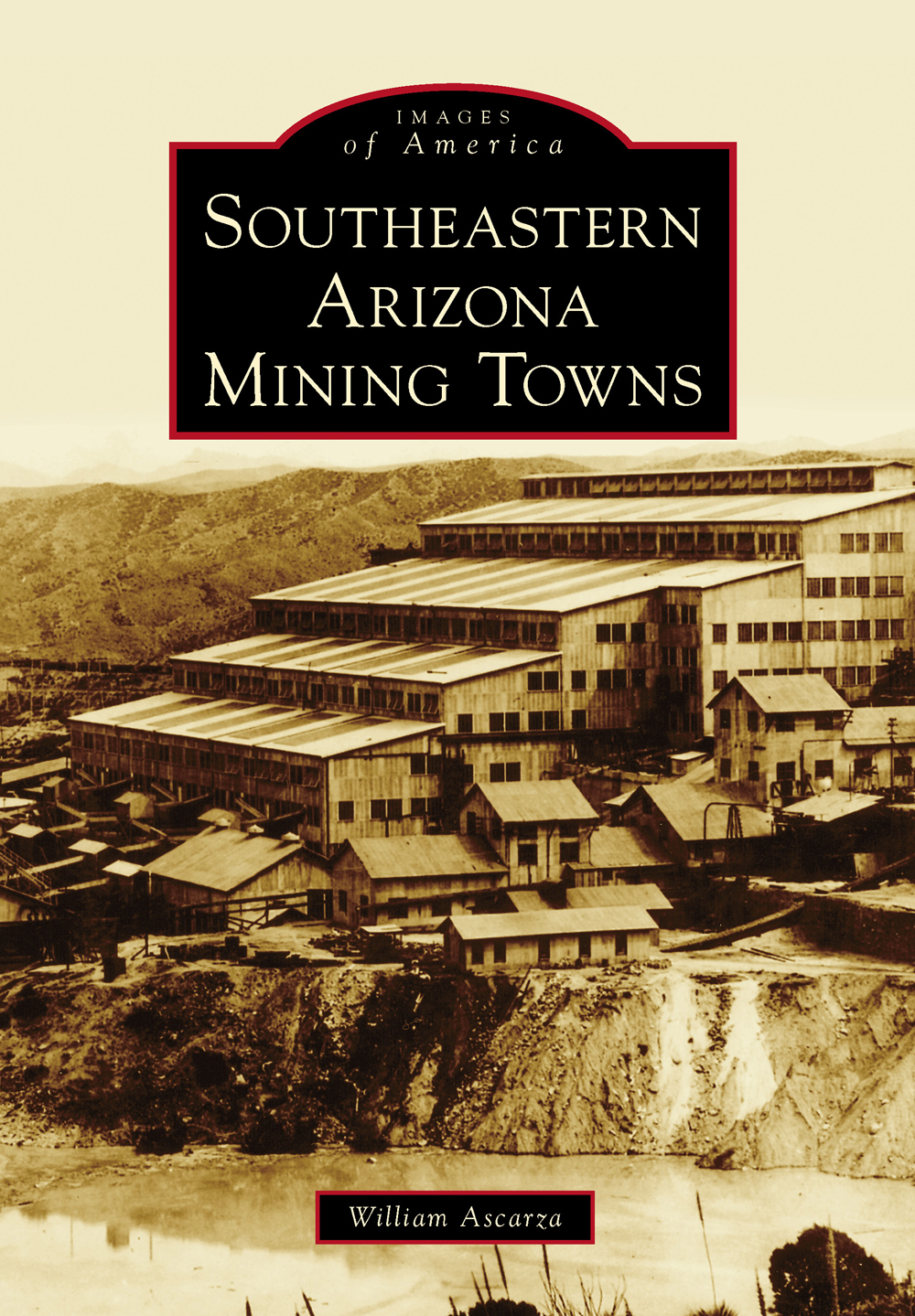

IMAGES

of America

SOUTHEASTERN

ARIZONA

MINING TOWNS

Perhaps no better representation of mining interests in the history of southeastern Arizona can be found than Tucsons official coat of arms. Designed in 1929 by Capt. Donald W. Page, the city building inspector, with the help of fire chief Joseph A. Roberts, Fr. Victor C. Stoner, and Mexican artist Jesus V. Zubiade, the coat of arms represents the four major historic political divisions in Tucson, including the Spanish Conquest, symbolized by the Pillars of Hercules; the Mexican eagle depicting the period of Mexican domination; the American eagle representing the sovereignty of the United States; and finally Arizona statehood symbolized above with a radiant star. Minor epochs represented in Tucsons history include the Jesuits and Franciscans with their arms of the Society of Jesus and the Order of St. Francis of Assisi. The presidio period and Apache warfare in the region appear with a wall overtopped by a black hill, while the battle flag of the Confederacy represents Tucsons role as the confederate capital in Arizona territory. All countries, participants, and groups represented in Tucsons coat of arms contributed to mining the mineral wealth in southeastern Arizona. The Tucson City Council adopted the coat of arms on February 19, 1929. (Photograph by the author; courtesy of the Arizona Historical Society.)

ON THE COVER: Surface equipment belonging to the Inspiration Consolidated Copper Company is evident in this image. Specifically, a hoist, compressor house, and coarse crushing plant positioned at the main shafts can be seen. This photograph was taken looking south toward the Pinaleno Mountain Range in 1911. By 1915, the first large-scale application of flotation was first used at the Inspiration Mine in Miami, Arizona. (Courtesy of US Geological Survey.)

IMAGES

of America

SOUTHEASTERN

ARIZONA

MINING TOWNS

William Ascarza

Copyright 2011 by William Ascarza

ISBN 978-0-7385-8516-1

Ebook ISBN 9781439649862

Published by Arcadia Publishing

Charleston, South Carolina

Library of Congress Control Number: 2011936454

For all general information, please contact Arcadia Publishing:

Telephone 843-853-2070

Fax 843-853-0044

E-mail

For customer service and orders:

Toll-Free 1-888-313-2665

Visit us on the Internet at www.arcadiapublishing.com

To my lovely wife, Lorie, who has been instrumental in supporting my endeavors to complete this book.

CONTENTS

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

I would like to thank the following individuals and institutions for providing me with access to historical information and print usage: Albertype Company; American Institute of Mining Engineers; Arizona Board of Regents for the University of Arizona; Arizona Historical Society; Arizona-Sonora Desert Museum; Arizona Geological Survey; Marilyn and Emmanuel Ascarza; Mark Ascher; Stacia Bannerman; Kevin Bays; Stan and Connie Benjamin; Marta Berry; Diane Braswell; Wendall Brown; Tallia Pfrimmer Cahoon; Mark Candee; Dan Caudle; Charles Cavalli; Lorie Cavalli; Kenny Don; Jez Gaddoura; Gleeson, Arizona, Museum; Greenlee County Historical Society; Jared Jackson; Peggy Larson; Dan Lee; Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division; Alvin F. Lindstrom; Mike Litchfield; Marylou Long; Magma Copper Company; Pat McClain; Tina Miller; Katherine Reeve; Hector Rodriguez; San Pedro Valley Arts & Historical Society; Gene Schlepp; Cosme Rodriguez Sesma; Ken Shake; Patty Sirls; Glenn Snow; Southern Methodist University, Central University Libraries, DeGolyer Library; Town of Mammoth; University of Arizona Mineral Museum at Flandrau Science Center; Tucson Gem & Mineral Society; US Geological Survey (USGS); US National Archives and Records Administration; and Richard Langley Ware Their generosity and time was invaluable in making this book a realisty.

INTRODUCTION

Arizona has a rich mining history dating back over 1,000 years. The indigenous people known as the Hohokam, or vanished ones, were the first to exploit the vast mineral resources in the landmass known today as Arizona. They used minerals such as copper and turquoise for ornamental jewelry and to trade among settlements. There is evidence that the Tohono Oodham (Papago) Indians mined hematite for use as war paint in the 15th century, shortly after the disappearance of the Hohokam. Native Americans were involved in mining turquoise in the Cerbat Mountains and cinnabar in the Castle Dome Mining District near Yuma. They also mined salt near Camp Verde. Although they were the first to mine the surface of Arizona, it was the Spanish who were the first to extensively penetrate its earth in search of mineral wealth, most notably in southeastern Arizona.

The Spanish first entered the region that was later called Arizona in the early 16th century. Their mission was to obtain the Three Gsglory, God, and goldfor the Spanish crown. Early Spanish exploration of Arizona began with the expedition led by Fray Marcos de Niza in 1539. The following year, his reports of great wealth in the form of gold and silver reached Francisco Vasquez de Coronado, who mounted several expeditions aimed at discovering the Seven Cities of Gold, which were rumored to rival the Aztec and Inca gold caches in Mexico and South America. The mineral wealth of the fabled Seven Cities of Gold proved elusive for the Spanish; however, they did succeed in establishing distant mining claims across the Southwest, including in southeastern Arizona.

During the time of Spanish rule, advancements were made in mining and refining minerals. The Spanish used an arrastra to pulverize ore deposits of gold and silver. Run by animal power, usually a horse or mule, the raw ore was crushed, sometimes amalgamated, and later sent to a sluice to separate the mineral content. The Spanish introduced the process of amalgamation to the New World in the 16th century as a means of separating silver from its ore. Mercury is mixed with silver removing it from its ore, forming amalgam. The applications of heat or nitric acid remove the mercury from the silver. Placer mining, which used techniques such as panning and the sluice box, was also conducted by the Spanish as a low-cost alternative for finding mineral wealth.

The arrival of the Jesuit missionary Eusebio Francisco Kino in the 1690s, along with the added protection of recently established missions of Guevavi, San Xavier del Bac, and Tumacacori, gave the Spanish impetus to explore the region for precious metals. According to the accounts of Father Kino, the Tubac-Tumacacori area was mined by both the Spanish and the Papago Indians for rich veins of gold and silver. Some sources speculate that the origin of the name Arizona may have been derived from a mining district called Real de Arizonac, which was located in northern Sonora and southwest of the present town of Nogales. The mine produced an abundance of silver during its operation in the late 1730s. Some silver specimens weighed in excess of 2,500 pounds. The area later became known as Planchas de Plata (slabs of silver) or Bolas de Plata (balls of silver).

Mining proved a risky venture in many parts of Arizona until the late 19th century because of the danger posed by the Apaches and Navajos. The Spanish continued to mine the region during a 30-year reprieve of hostilities brought about by Viceroy Bernardo de Galvezs introduction of the Peace by Deceit plan. In return for a cessation of hostilities against the Spanish, the Native Americans were given food, guns, and whiskey. Hostilities in the region resumed after Father Miguel Hidalgos Grito de Delores, which initiated Mexicos long war for independence from Spain. The Mexican Revolution of 1822 further reduced military protection for miners in the American Southwest against the onslaught of deprivation perpetrated by Apaches and outlaws.

Next page