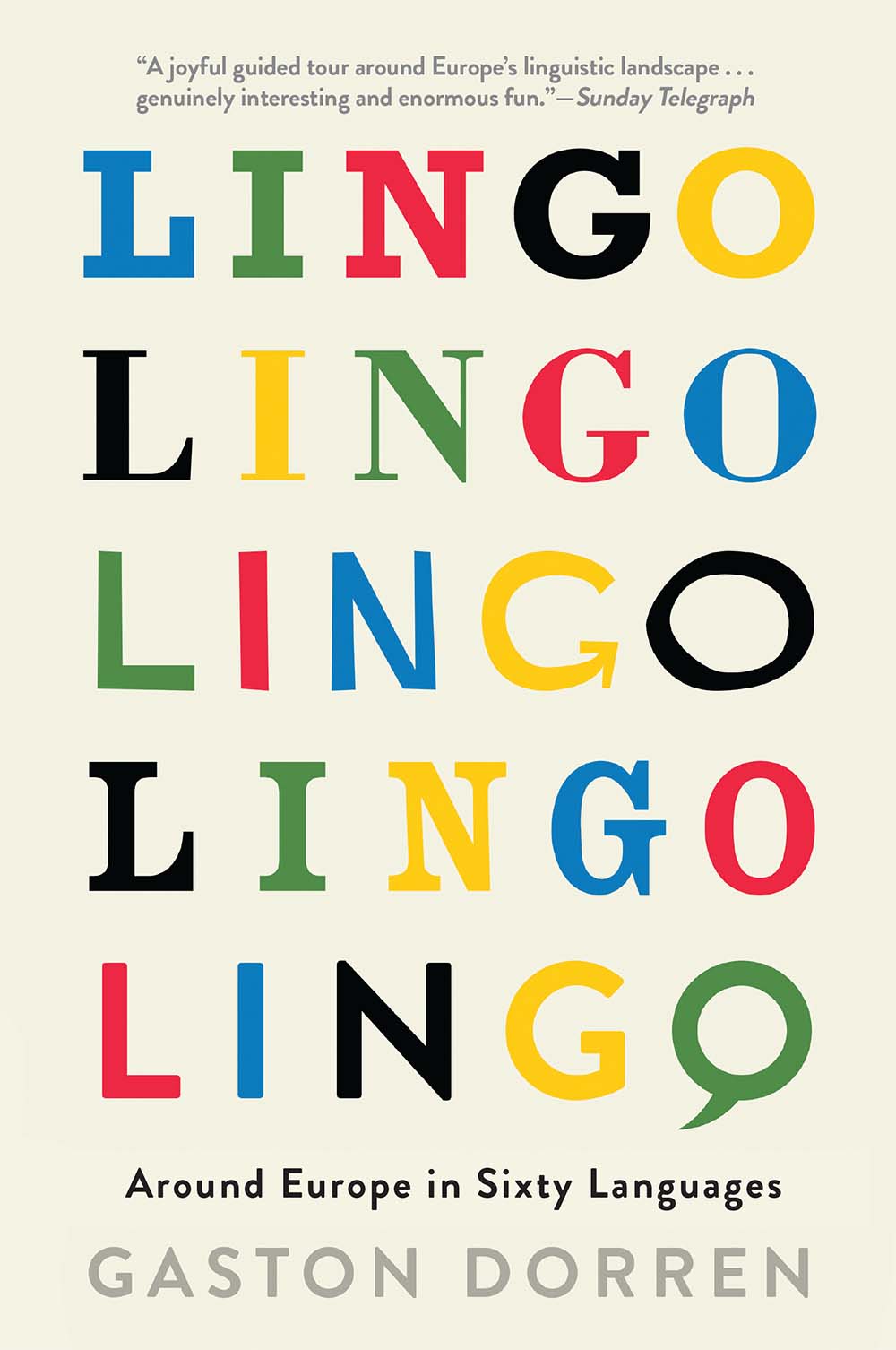

Lingo

Around Europe in

Sixty Languages

Lingo

Around Europe in

Sixty Languages

Gaston Dorren

With contributions by

Jenny Audring, Frauke Watson

and Alison Edwards (translation)

Atlantic Monthly Press

New York

Copyright 2015 by Gaston Dorren

Jacket design by Keenan

Author photograph by Bram Petraeus

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form or by any electronic or mechanical means, including information storage and retrieval systems, without permission in writing from the publisher, except by a reviewer, who may quote brief passages in a review. Scanning, uploading, and electronic distribution of this book or the facilitation of such without the permission of the publisher is prohibited. Please purchase only authorized electronic editions, and do not participate in or encourage electronic piracy of copyrighted materials. Your support of the authors rights is appreciated. Any member of educational institutions wishing to photocopy part or all of the work for classroom use, or anthology, should send inquiries to Grove Atlantic, 154 West 14th Street, New York, NY 10011 or .

First published in Great Britain in 2014 by Profile Books,

3A Exmouth Market, London, EC1R OJH.

profilebooks.com

Published simultaneously in Canada

Printed in the United States of America

This book was published with the support of the

Dutch Foundation for Literature.

.png)

ISBN 978-0-8021-2407-4

eISBN 978-0-8021-9094-9

Atlantic Monthly Press

an imprint of Grove Atlantic

154 West 14th Street

New York, NY 10011

Distributed by Publishers Group West

groveatlantic.com

Contents

What Europeans speak

Next of tongue

Languages and their families

| Lithuanian

| Finno-Ugric Languages

| Romansh

| French

| Slavic languages

| Balkan languages

| Ossetian

Past perfect discontinuous

Languages and their history

| German

| Galician

| Danish

| Channel Island Norman

| Karaim, Ladino and Yiddish

| Icelandic

PART THREE War and peace

Languages and politics

| Norwegian

| Belarus(s)ian

| Luxembourgish

| Scots and Frisian

| Swedish

| Catalan

| Serbo-Croatian

Werds, wirds, wurds ...

Written and spoken

| Czech

| Polish

| Scots Gaelic

| Russian

| Following the clues

| Spanish

| Slovene

| Shelta and Anglo-Romani

PART FIVE Nuts and bolts

Languages and their vocabulary

| Greek

| Portuguese

| Sorbian

| Latvian

| Italian

| Sami

| Breton

Talking by the book

Languages and their grammar

| Dutch

| Romani

| Bulgarian-Slovak

| Welsh

| Basque

| Ukrainian

Intensive care

Languages on the brink and beyond

| Mongasque

| Irish

| Gagauz

| Dalmatian

| Cornish

| Manx

Movers and shakers

Linguists who left their mark

| Slovak

| Albanian

| Germanic languages

| Esperanto

| Macedonian

| Turkish

Warts and all

Linguistic portrait studies

| Finnish

| Faroese

| Sign languages

| Armenian

| Hungarian

| Maltese

| English

*

Introduction

What Europeans speak

T he attitude of English speakers to foreign languages can be summed up thus: lets plunder, not learn them. A huge proportion of English vocabulary is of French, Latin or otherwise non-native origin. But English speakers the world over have never had much of a taste for acquiring a foreign language in its entirety. Anything short of speaking the language I shall be delighted to undertake, Dickens had Mr Meagles say in Little Dorrit , while a century and a half later, British comedian Eddie Izzard explains his countrys monolinguals: Two languages in one head? No one can live at that speed.

These are caricatures, of course, but the British passion for language, though intense, generally takes form in a somewhat exclusive fascination for English. Not only are the British incorrigible punners and ardent crossword puzzlers, but many are also enthralled by the history and diversity of the native tongue. And while Americans love to joke about weird British spellings, I wonder how many would really want it otherwise. All this weirdness makes for excellent stories. What more could one wish for?

Well, how about the life of other languages? In both their spoken and written forms, Europes scores of languages may sound and look forbidding, but the stories about them are compelling. This book sets out to tell sixty of the best. You will hear how French, seemingly so mature, is really guided by a mother fixation. You will discover why Spanish sounds like a submachine gun. And if you thought German spread across Europe at gunpoint, prepare to be proved wrong. You will also venture further afield, as we explore the oddly democratic nature of Norwegian, the gender-bending tendencies of Dutch and the linguistic orphans of the Balkans. Yet further off the beaten track you will be guided to the ancient heirlooms of Lithuanian, the snobbery of Sorbian and the baffling ways of Basque. And believe it or not, some of Europes most incredible language stories are to be found right on Britains doorstep outlandish and inlandish at the same time, so to speak, in the islands Celtic and travellers tongues.

Lingo is a guidebook of sorts, but in no sense an encyclopedia: while some chapters are short portraits of entire languages, others centre on an individual quirk or personality. It is intended, as the French so enticingly put it, as an amuse-bouche .

Gaston Dorren, 2015

These two symbols are used at the end of each section, mainly to entertain.  introduces a word or two that English has loaned from the language under discussion, while

introduces a word or two that English has loaned from the language under discussion, while  highlights a word that doesnt exist in English but perhaps should.

highlights a word that doesnt exist in English but perhaps should.

PART ONE

Next of

tongue

Languages and their families

Europes two big language families are Indo-European and Finno-Ugric. The lineage of Finno-Ugric is fairly straightforward, as are its modern variants (Finnish, Hungarian, Estonian). But the pedigree of the Indo-Europeans is a real tangle that ranges through Germanic, Romance and Slavic languages, and more. In some respects, though, its story is like any other family saga, complete with conservative patriarchs (Lithuanian), bickering children (Romansh), spitting-image siblings (the Slavics), forgotten cousins (Ossetian), orphans (Romanian and other Balkan languages) and kids who find it hard to cut the apron strings (French).

The life of PIE

Lithuanian

O nce upon a time , thousands of years ago (nobody knows quite when), in a faraway land (nobody knows quite where), there was a language that no one speaks today and whose name has been forgotten, if it ever had one. Children learned this language from their parents, just as children today do, and they in turn passed it on to their children, and so on and so forth, for generation after generation. In the course of all the centuries, the old language underwent constant change. It was a bit like the game of telephone: the last player hearing something quite different from what the first actually said. In this case, the last players are us.

.png)

introduces a word or two that English has loaned from the language under discussion, while

introduces a word or two that English has loaned from the language under discussion, while  highlights a word that doesnt exist in English but perhaps should.

highlights a word that doesnt exist in English but perhaps should.