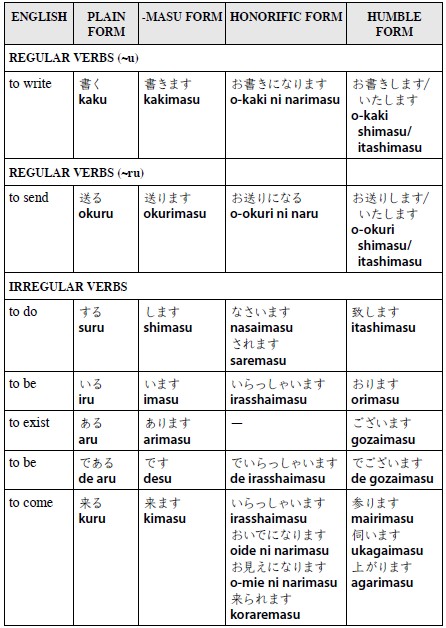

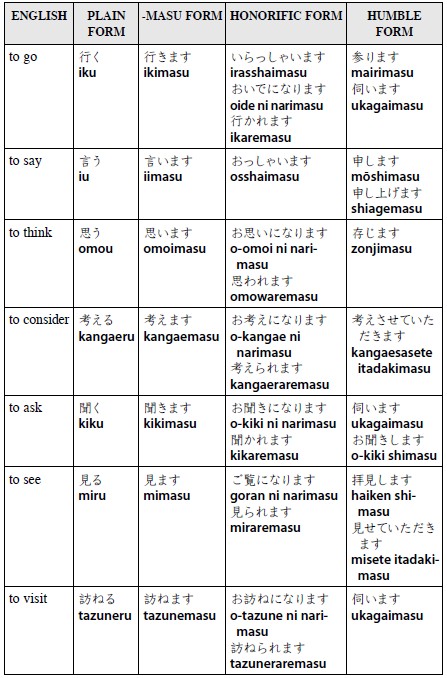

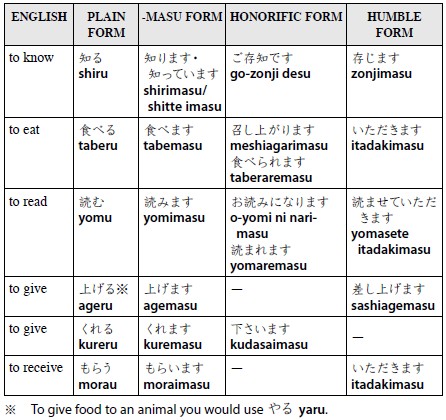

The following table provides a guide to the different levels of politeness for some common Japanese verbs. The plain form is used for informal speech between friends and family, the masu form is used in general conversation outside this circle, the honorific form is used to refer politely to others, and the humble form for referring deferentially to yourself. It covers basic usage when addressing a second person. The language for showing respect to a third person is not covered.

The passive is included in this table along with the other honorific forms as it is widely used to show respect to the person youre speaking to. However, it is not strictly an honorific, belonging rather to the group of words known as polite language. This perhaps accounts for its popularity as it may appear more informal, showing respect without putting the person on a pedestal. But take care not to overdo it.

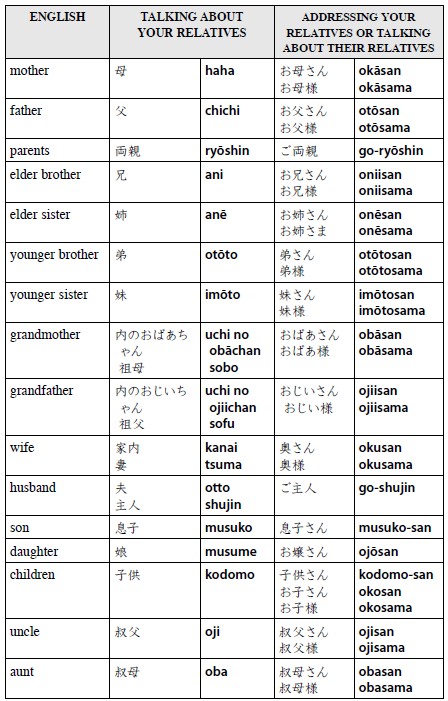

When speaking to your own or your spouses father or mother, use otsan and oksan ; but when speaking about them to people outside your family, use chichi and haha , respectively. Only children use otsan and oksan when talking about their own parents.

Usage is not so strict concerning the terms for grandparents. The terms ojiisan (grandfather) and obsan (grandmother) can be used when speaking to friends, but otherwise the more formal terms sofu and sobo should be used.

Chapter The Fundamentals

1.01 Greeting People

1.02 Follow-up Expressions

1.03 Commenting on the Weather

1.04 Being Introduced

1.05 Saying Goodbye

1.06 Expressing Gratitude

1.07 A Few Notes on Respect Language

1.08 Apologizing

1.09 Asking Permission

1.10 Making Requests

1.11 Leading up to a Request

1.12 Refusing Requests

Chapter

The Fundamentals

G reetings and other set expressions help any society run smoothly. In Japan, these phrases delineate relationships, offer face-saving ways to deal with difficult situations, and provide a convenient shorthand for expressing thanks or regret. In Japanese there is no need to be original; in most situations, there is no phrase better than the set phrase.

Ive run through the main greetings, but you will need to follow these up with a word of thanks. When meeting in person or on the phone, people seem to have this remarkable facility for remembering your last encounter. Its embedded in the language. So use some of the follow-up expressions listed as a kind of shorthand. Just a phrase, and a set phrase at that, recreates the circumstances of the last time you met. Theres no need to go into detail. With that one set phrase you have reinforced the relationship.

Relations are quite formal in Japan, with proper introductions being the norm. Again there are set phrases. After you get used to it you may find this way of dealing with people quietly reassuring.

Bowing is infectious, and after a while youll probably start doing it too. If youre going to do it, you might as well do it right. A proper bow ( o-jigi ) is from the waist: about 15 degrees is fine for most situations. Men keep the arms straight at the sides, women place their hands in front. A nod of the head ( eshaku) is also used for brief thanks or to acknowledge people when you meet them. No need to be obsequious, and dont stick your head out like a chicken.

This chapter also includes some notes on respect language. All languages have different levels of politeness. Ive tried to explain the basic principles and there will be examples throughout the book. Its part and parcel of the language.

Finally, avoid the use of pronouns. Anata translates as you but its use is generally avoided. (One exception is when wives call their husbands anata it has the special meaning of darling.) When talking to someone, you can be safe and say his or her name, with the suffix - san , every time you want to say you. Otherwise, refer to teachers, doctors, speakers, and government officials as sensei (teacher), and higher ranking members in your company by their titles. For example, if you want to ask your managers opinion, say, with a rising intonation, Kach no o-kangae wa? Similarly, the use of the first person pronoun meaning I ( watashi wa ) sounds as if youre drawing attention to yourself. Generally, its not necessary for the sense of the sentence.

So, to get started, here are some basic greetings and phrases to use in different situations with, for your interest, some notes on their usage.

1.01 Greeting People aisatsu

Ohay gozaimasu Good Morning

Its early is the literal meaning and it was originally used to thank people coming into work. Its still used in this sense in the entertainment industry when someone starting work in the afternoon will be greeted like this. Friends drop the gozaimasu .

Konnichi wa Good afternoon or Hello

Used from late morning to late afternoon but not as much as Hello or Ohay gozaimasu . Its not usually said to colleagues or family members. When you feel you should be polite, say Shitsurei shimasu (below) instead.

Konban wa Good Evening

This too is somewhat more limited in its use. If youre living with a Japanese family, it might make you sound standoffish, as if you dont want to be treated like a member of the family.

Shitsurei shimasu/O-jama shimasu

/

Excuse me ( lit . I am about to disturb you)

Either of these two polite expressions would be appropriate when entering or leaving someones home or office.

Tadaima Im home!

The response by those in the house is Okaeri-nasai . Said by a waiter in a restaurant, tadaima means right away.

1.02 Follow-up Expressions

Quickly think back to the last time you met the person and use one of these phrases. If you met them recently you could simply say:

Konaida wa dmo.

Thank you for the other day.

Or more politely

Senjitsu wa dmo arigat gozaimashita.

Thank you very much for the other day.

If you went to their house or they treated you to a meal, be sure to say,

Konaida wa dmo gochis-sama deshita.

Thank you for the meal/drinks the other day.