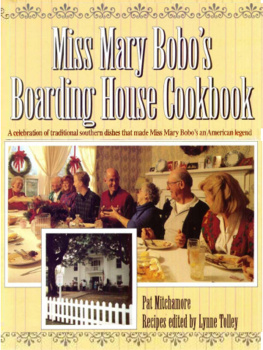

Dinner at Miss Ladys

MEMORIES AND RECIPES FROM A SOUTHERN CHILDHOOD

by Luann Landon

Algonquin Books of Chapel Hill

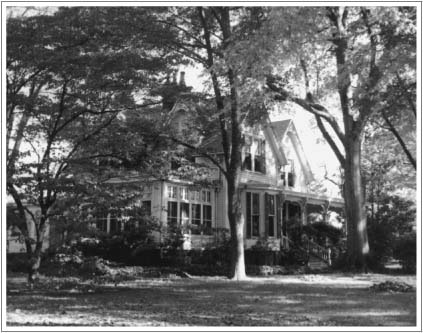

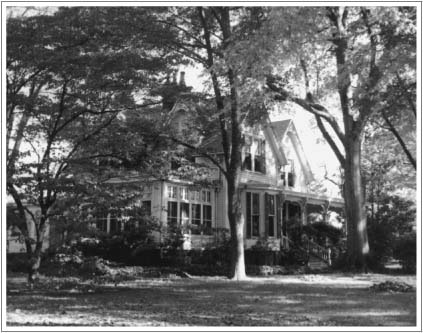

Miss Ladys house

Published by

ALGONQUIN BOOKS OF CHAPEL HILL

Post Office Box 2225

Chapel Hill, North Carolina 27515-2225

a division of

Workman Publishing

225 Varick Street

New York, New York 10014

1999 by Luann Landon. All rights reserved.

Grateful acknowledgment is made to the following copyright holders, publishers, or representatives for permission to reprint recipes on the pages listed: Recipe on from More Gems by

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data is available.

ISBN 978-1-565-12227-7

EISBN 978-1-565-12723-4

For my

husband, David,

and my mother,

Luann

I would like to thank friends and relatives without whom I could not have brought this book to completion. Charlotte and Edgar de Bresson suggested I write the book, and my talented editor at Algonquin, Kathy Pories, helped me craft the final version. My thanks to many others for reading and tasting, for giving recipes, encouragement, and help with the manuscript: Elizabeth and Tony Harrigan, Elizabeth Hanson, Susan Van Riper, Penny Phillips, Panna Ansley, Leila Fowler, Alison Touster-Reed, Eva Touster, Luda Davies, Carolyn Newbern, Bob Sullivan, Janine and Jean-Pierre Limet, Claude and Vincenette Pichois, Mme. Georges Duby, Ruth and Francis Seton, Jo Church, Nancy Weatherwax, Jim Jones, Nancy Blackwelder, Leslie Richardson, Mildred Merritt, the late Catherine Booth, Wilma Tate, Cherry Clements, the late Mrs. Wayne J. Holman, Jr., and Louise Ware.

A Note on the Recipes

In writing about the South I knew as a child, I have used my memory and my imagination. This is the life I remember and want to remember. If, in some cases, I could not recall what food was served on a particular occasion, I created menus that would likely have been served. My grandmothers cook, Henretta, inspired my love of good food, but she never wrote down any of her recipes. Some of them were written down by my Aunt Virginia, who gave them to me. I have re-created Henrettas other recipes from memory, experimenting with each one until I achieved the authentic taste that I remember so well. Using those and other recipes handed down by grandmothers, aunts and great-aunts, and cousins, or occasionally given to me by friends or selected from my library of Southern cookbooks, I have attempted to create meals both reflective of that time and accessible to contemporary cooks.

L.L.

Contents

Henretta and Aunt Virginia

INTRODUCTION

I WAS BORN IN Greensboro, Georgia, a small town eighty miles east of Atlanta, where my fathers family had lived for a hundred and fifty years. In that small town, my family had a history. We had lived through, and lost, a war, and somehow, in the long run, we had won. We had inherited ways of doing thingsspeaking, writing, building, cooking.

In Greensboro there were three family houses. After we moved to Nashville, my sister and I spent our summers with our grandparents, Miss Lady and Judge, in Miss Ladys family home. We visited and played in the other two family housesCousin Evas, across the street, and next door, the home of Miss Annie, Miss Ladys sister. The yards around these houses were full of magnolia, pecan, cedar, copper beech, mimosa, oak, and fruit trees; in the gardens grew lilies, gardenias, hydrangeas, roses, and camellias. Memories of my childhood are filled with wonderful cooking smells and the hush of shaded porches. It was a life that was wholesensuous and unhurried, it had a certain feel, a characteristic taste.

My mothers mother, Murlo, was from outside. After my fathers death, she came to live with with us in Nashville and sometimes accompanied us to Greensboro. Murlo was an accomplished cook and made everything herself, unwilling to entrust her recipes to someone elses ignorance or carelessness. My fathers mother, Miss Lady, was waited on by servants all her life and didnt even know how to make a cup of tea, but she had an infallible sense of how food should taste.

I hope my book will evoke an experience of life in the old South, as I knew it in my childhood, from family stories, posed sepia photographs preserved in albums, and velvet and silk clothes carefully packed in cedar chests. It was a life centered around the meals that took place in family dining rooms. The dining room was the heart of every old Southern home. Here the family gathered every day, gave thanks to the Lord for his blessings, talked of ancestors and descendants, weddings and christenings, gardens and fields. Life that had happened and life that might happen. Time passed sweetly and unhurriedly. We liked to think that we honored the past, celebrated the present, and took courage for the future.

Unlike most members of my generation, I grew up with old people. My family lived in small Southern towns or the old neighborhoods of cities in a time when the majority of the population had relocated to the suburbs. The older people in my family, not only grandparents but also aunts and uncles, great-aunts and great-uncles, and first and second cousins, either lived with us or came to stay for long visits, and they were very much engaged in our upbringing. They taught me the things that they had been taught and thought important to pass on. Perhaps the most important thing they taught me was the significance of good taste in all its forms.

Now that I look back on that time, it seems to me that taste was the most important thing in our livescertainly of the utmost importance to my grandmothers who brought me up. Murlo and Miss Lady were Victorian Southern women. They expected me to have good manners, to behave well. But they also taught me how to season with just the smallest amount of salt added to the sweet, just the right amount of vanilla or rosewater or brandy; how to balance the wings of a flower arrangement and set a table; how the textures of fine materials should feel; which colors go together harmoniously.

I remember spending long afternoons looking at Miss Ladys art books filled with color reproductions of European paintings. I loved the rich and subtle colors and shapes and the finery of the womens clothes. My sister, Susan, and I would dress up in the old things stored in the upstairs closets and cedar chestswed try on our great-grandmothers shifts, lace-trimmed and finely tucked petticoats, and trousseau dresses, or wed slip into Miss Ladys old evening dresses. We would find an old ivory and lace fan or a fading silk rose and practice posing, pretending we lived in the world of Van Dyke or Gainsborough.

Food was very important in our world. Murlo insisted on using fresh ingredients and making everything herself without taking shortcuts. She would get up very early every morning (after three or four hours of sleepshe spent most of the night reading) and make freshly squeezed orange juice, hot oat-meal with brown sugar and milk, and whole-wheat toast. Breakfast at Miss Ladys house, always prepared by Henretta, consisted of toast made from light bread, grits swimming in butter, scrambled eggs, bacon, and homemade preserves. There was a running controversy between Murlo and Miss Lady: breakfast in Greensboro was pure self-indulgence, like Miss Lady herself, whereas Murlos breakfast was sensible, good for you.