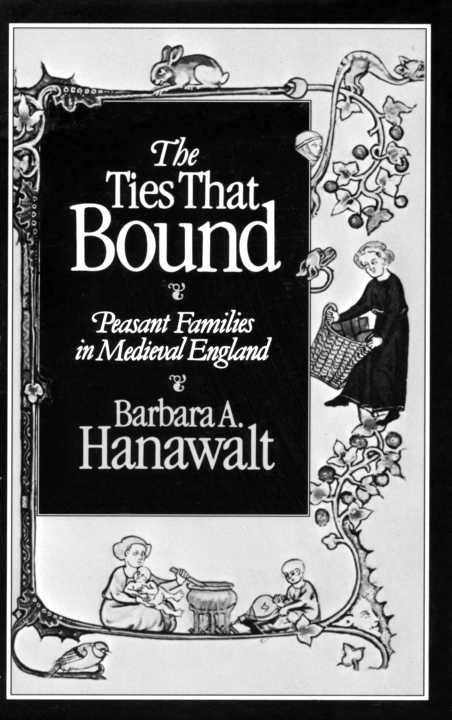

Hanawalt - The ties that bound: peasant families in medieval England

Here you can read online Hanawalt - The ties that bound: peasant families in medieval England full text of the book (entire story) in english for free. Download pdf and epub, get meaning, cover and reviews about this ebook. City: New York;Angleterre;England;Oxford, year: 1988;2010, publisher: Oxford University Press, genre: Home and family. Description of the work, (preface) as well as reviews are available. Best literature library LitArk.com created for fans of good reading and offers a wide selection of genres:

Romance novel

Science fiction

Adventure

Detective

Science

History

Home and family

Prose

Art

Politics

Computer

Non-fiction

Religion

Business

Children

Humor

Choose a favorite category and find really read worthwhile books. Enjoy immersion in the world of imagination, feel the emotions of the characters or learn something new for yourself, make an fascinating discovery.

- Book:The ties that bound: peasant families in medieval England

- Author:

- Publisher:Oxford University Press

- Genre:

- Year:1988;2010

- City:New York;Angleterre;England;Oxford

- Rating:4 / 5

- Favourites:Add to favourites

- Your mark:

- 80

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

The ties that bound: peasant families in medieval England: summary, description and annotation

We offer to read an annotation, description, summary or preface (depends on what the author of the book "The ties that bound: peasant families in medieval England" wrote himself). If you haven't found the necessary information about the book — write in the comments, we will try to find it.

Hanawalt: author's other books

Who wrote The ties that bound: peasant families in medieval England? Find out the surname, the name of the author of the book and a list of all author's works by series.

The ties that bound: peasant families in medieval England — read online for free the complete book (whole text) full work

Below is the text of the book, divided by pages. System saving the place of the last page read, allows you to conveniently read the book "The ties that bound: peasant families in medieval England" online for free, without having to search again every time where you left off. Put a bookmark, and you can go to the page where you finished reading at any time.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

BARBARA A. HANAWALT

For the men of my family: my father, Nelson; my brother, Ronald; and my husband, Ronald Nelson

In his great study English Villagers of the Thirteenth Century, George Homans lamented that "in the absence of a great contemporary novel about the husbandmen, we cannot follow them into the intimate life of their homes." In his section on village families he limited his discussion to those aspects of family life that appear so prominently in manorial court rolls, bloodlines and inheritance of family land. Writing in 1941, he could not have predicted the amazing dynamism that has transformed research in social history. Medieval historians have used those same court rolls to open up the networks of intrafamilial and intravil- lage interactions; they have opened the doors of village homes. Archaeologists working on medieval village sites have laid bare the floor plans of these homes. Finally, the emotional interactions of the husbandman's family may be investigated, not through a contemporary novel, but through wills and, most importantly, through the cases of accidental death that appear on the coroners' rolls. Each inquest into a misadventure reads, not like a novel or even a short story, but like a very succinct verbal snapshot of life. The intimate detail of the scenes comes through in rich texture as neighbors and witnesses reconstructed what had happened.

The present study will enter the doors of the peasant's house. The first section considers the material environment of the family, starting on the ground with the archaeological work but constructing the rest of the house, furnishing it, and filling its larders and clothes chests. The second section assesses the recent scholarship on blood and land that Homans pioneered. The third investigates the heart of the peasant household, the family economy, presenting a model for the functioning of the economic unit and investigating the contributions of husband, wife, children, and servants. In the fourth part the affective bonds of family members and life stages receive detailed consideration. Finally, surrogates for family form a fifth section dealing with godparents, neighbors, social-religious gilds, and religious institutions.

This book cannot be definitive, but it is designed to pull together information about medieval peasant families that appear in a variety of secondary works and add a substantial body of new material from the accidental-death inquests from the coroners' rolls. I have attempted to present as complete a synthesis of work on the late medieval English peasant family as is currently possible. Gaps are inevitable and not all readers will agree with the thesis. Controversy, however, will be useful to the field. For too long we medievalists have discussed family as a reply to the medieval straw family that historians Philippe Aries, Lawrence Stone, Edward Shorter, and Alan Macfarlane constructed for us. Their descriptions of medieval peasant families are designed to show how different the modern family is from the medieval one. Medievalists have declared the straw family wrong on a number of specific points, but we have lacked a comprehensive discussion of our own to which to refer.

Some historians will object that regional variations are so great that a synthesis is impossible. I am not denying the importance of regional variations; they are vitally important in a country that was settled by Celts, Romans, Angles, Saxons, Frisians, Jutes, Danes, Norwegians, and Normans. Furthermore, the geography is not homogeneous but varies with marshes, woods, hills, plains, heath, and soils that are sand, clay, and gravel. Ecological factors are bound to influence settlement patterns and cultivation practices. But to remain rooted in one village or one region handicaps comparative discussions and obscures the broader picture of common customs and practices among medieval peasant families. Many aspects of family life cut across these boundaries, for they are more rooted in biology than in inheritance practices or variations in cultivation.

In writing a synthetic study of the family, I have relied heavily on excellent regional and local studies, on the publications of county record societies, and on the work of antiquarians and historians of earlier generations. These debts are recognized in specific footnote references. In the field of English social history, however, there are exemplary historians who have substantially changed the way we have conducted research on the peasantry. To G. R. Coulton I owe the debt of his own work on the manor and also the number of imaginative students whom he trained in the field. Eileen Power, with her gift of bringing medieval people alive through fine writing, has been a model for many, including myself. She has shown us all that good scholarship need not be obscure and pedantic. J. Ambrose Raftis, in his pioneering work on village reconstitution from manorial records, permanently removed any temptation to look at peasantry as an amorphous class without internal wealth and status divisions. R. H. Hilton's many studies on the English peasantry, particularly his Ford Lectures, have brought a valued level of sophistication to the field. My debts to my mentor, Sylvia Thrupp, become increasingly obvious to both of us and bring a mutual pleasure and amusement that over the years she was actually teaching me and I learned.

Without borrowing from anthropology, a study of peasant families would be incomplete. I am particularly grateful to Eric Wolf for the training I received from him as a graduate student at the University of Michigan. More than he is aware, he had a strong influence on the direction and thesis of this book.

In taking a new direction in research, I have had to learn new areas of scholarship and new methodologies. In the summer of 1974 I took a seminar with David Herlihy on the medieval family and demographic history at the Southeastern Institute for Medieval and Renaissance Studies. His initial influence on the project has carried through the whole of it. I also attended an institute on quantification and demographic history at the Newberry Library in the summer of 1978. The lectures and readings in connection with these courses initiated my reading in the modern history of the family and confirmed my desire to present a coherent picture of the medieval family.

In the course of researching a broad topic such as this one, blocks of time free from teaching and access to archives and computers are necessary. The American Philosophical Society generously provided me with the initial funds to survey the coroners' inquests, and Indiana University granted me a Summer Faculty Fellowship to return to the Public Records Office in London for further research. The university also provided funds to purchase microfilm, hire research assistants, and have access to their computing facilities. The staff of the Public Record Office were the courteous helpers that I have always found them to be. My two research assistants, Madonna Hettinger and Benjamin McRee, have gone on to become fine medieval historians in their own right. The Newberry Library, through a National Endowment for the Humanities Senior Research Fellowship, permitted me to use their excellent collection of printed primary sources that has formed a large part of this study. At the same time the Newberry was a congenial and intellectually stimulating environment in which to work. The members of their Fellows Seminar all contributed to my thinking on this project. Finally, the Institute for Advanced Study at Princeton provided a perfect environment for writing the first draft of this book. Again, the National Endowment for the Humanities, matching a sabbatical from Indiana University, made the year possible. With the year at the institute still fresh in my mind, I would like to list everyone on the staff and among the fellows who made life so pleasant and intellectually alive, but this is not the place to reproduce their telephone directory. Two of my colleagues, Norman J. G. Pounds and George Alter, were kind enough to read portions of the manuscript and share with me their expertise in archaeology and demography, respectively. My warm thanks to all who have directly or indirectly helped on this project.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

Similar books «The ties that bound: peasant families in medieval England»

Look at similar books to The ties that bound: peasant families in medieval England. We have selected literature similar in name and meaning in the hope of providing readers with more options to find new, interesting, not yet read works.

Discussion, reviews of the book The ties that bound: peasant families in medieval England and just readers' own opinions. Leave your comments, write what you think about the work, its meaning or the main characters. Specify what exactly you liked and what you didn't like, and why you think so.