Contents

For my parents

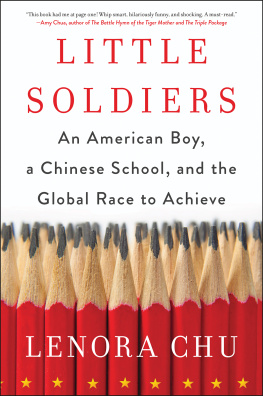

I am a little soldier, I practice every day.

I raise my binoculars, I see things clearly.

I take a wooden gunbang, bang, bang!

I drive a small gunboatboom boom boom!

I ride as a cavalrymango go go!

I am a little soldier, I practice every day.

One-two-one, one-two-one, Let us forward march!

FOR... WARD... MARCH!

A song taught in Chinese kindergarten

Prologue

The Red Star

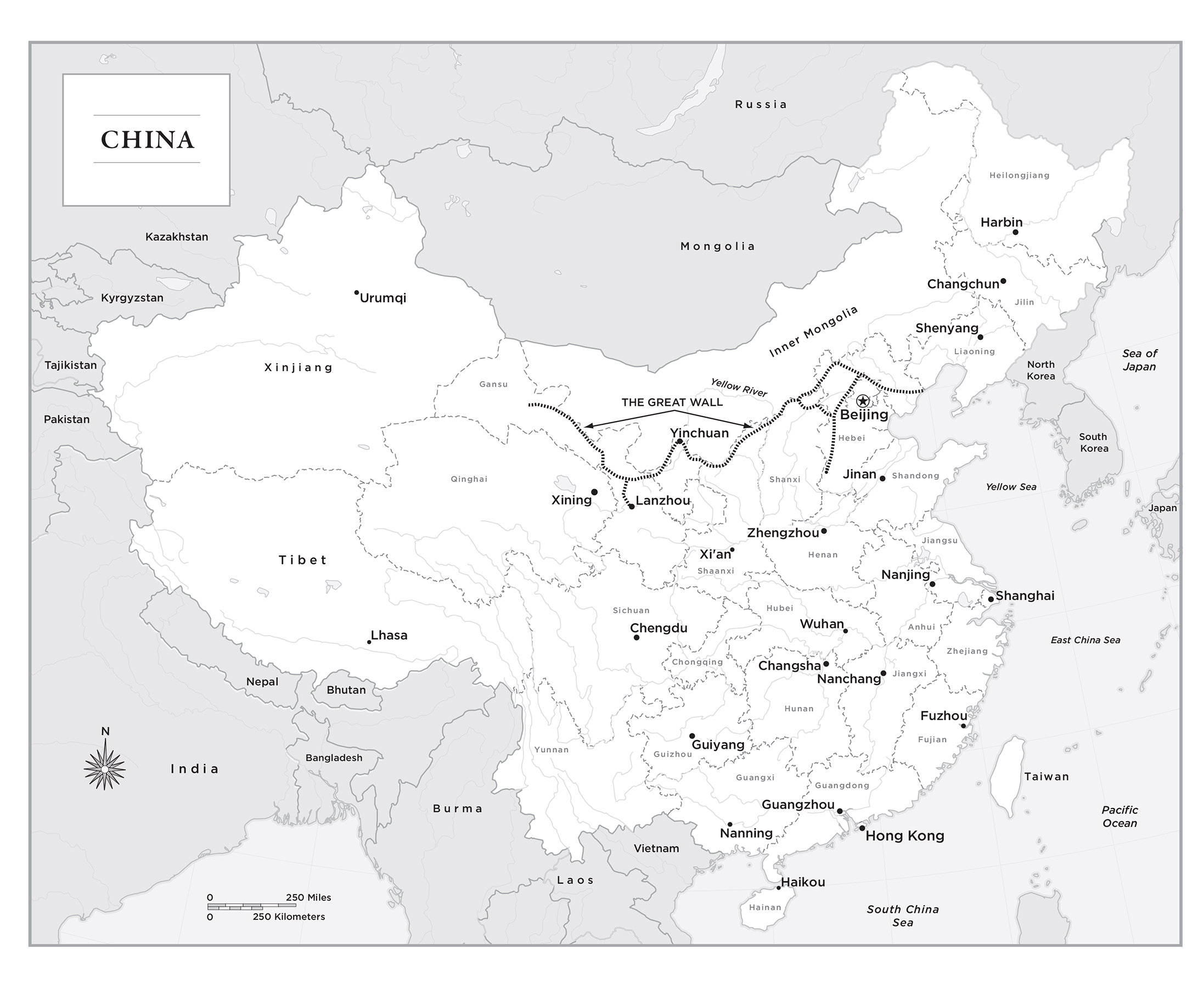

It seemed like a good idea at the time. When my little boy was three years old, I enrolled him in a state-run public school in Shanghai, Chinas largest city of twenty-six million people.

Were Americans living and working in China, and the Chinese school system is celebrated for producing some of the worlds top academic achievers. We were harried, working parentsIm a writer, my husbands a broadcast journalistmotivated by thoughts of When in Rome... as well as a desire for a little Chinese-style discipline for our progeny. Our son would also learn Mandarin, the most widely spoken language in the world. Excuse me for thinking, What was not to like?

It seemed an easy decision. And two blocks from our home in downtown Shanghai was Soong Qing Ling, the school, as far as posh Chinese urbanites were concerned. Soong Qing Ling Kindergarten educated the three- to six-year-old children of ranking Communist Party officials, wealthy entrepreneurs, real estate magnates, and celebrities. Strolling past on weekends, I sometimes spotted young Chinese parents gazing through the schools entrance gates, as if daydreaming about a limitless future for their child. Inside a culture where the early years are considered so critical that theres a common saying: , or Dont lose at the starting gate, we figured Soong Qing Ling was among the best education experiences China had to offer.

A transformation began almost immediately. After the school year began, I noticed my normally rambunctious toddler developing into a proper little pupil. Rainey faithfully greeted his teacher with Laoshi zao!Good morning, Teacher! He began heeding the teachers every command, patiently waiting his turn in lines, and performing little duties around the house when asked.

He also began picking up Mandarin, along with a dose of what the culture valued: hard work and academics. One day, Rainey tried to decipher the meaning of a Chinese phrase hed heard in the classroom.

What does congming mean? he asked me, large brown eyes wide.

Congming means smart, Rainey, I responded.

Oh, good. I want to be smart, he said, bobbing his head. He wrinkled his nose. What does ke ai mean?

That means cute, I said, and his eyes widened.

Oh! I dont want to be cute. I want to be smart, Rainey said.

One afternoon, he emerged from school with a shiny red star plastered to his forehead.

Who gave you that star? I asked my son.

My teacher! I was good in school, Rainey chirped, glancing up at me as I studied his face.

What do you get a red star for? I ventured, always curious about his classroom environment. Do you get it if you run fast?

Rainey laughed, a hearty guffaw that emanated from his tiny belly and up through his throat, as if Id just uttered the most ridiculous thing hed ever heard.

Mom, I never get a star for running in the classroom, he said, smirking, large, brown eyes dancing. I get it for sitting still.

Sitting still? I immediately recognized the error in my assumptions. In America, a student might be rewarded for extraordinary effort or performance, for rising a head above the rest. In China, you get a star for blending in and for doing as youre told. It was Americas celebrity culture versus Chinas model citizen; standing out versus fitting in; individual excellence versus the merit of collective behavior.

The Chinese way was certainly familiar to me, the daughter of Chinese immigrants to America. Yet Im also a product of US public schools and their culture of personal choice, and as a parent, I wanted good habits instilled for the right reasons, and delivered with a firm but featherlight touch. I began to wonder: Were Raineys teachers instilling the right values?

Why do you sit? Do they make you sit at school? Do you have to sit? I asked Rainey, my voice increasing in pitch and speed with each query.

But my rapid-fire questions were too much for a three-year-old. My husband, Rob, told me it sounded as if I were saying, Are your human rights being violated?

A few weeks later, Rainey suddenly announced at dinner, over stir-fried tofu, Lets not talk while were eating.

Where did you get that idea? I said, immediately on the case. Did the teachers say that?

On this, Rob was also incredulous. So you cant speak during lunch, Rainey?

No. Bei Bei and Mei Mei were talking and the teacher said, Be quiet. Sometimes the teachers are angry to us, Rainey said, as Rob shook his head. Some of the fondest memories from my Texas childhood come from the school lunch table; there, we learned to barter peanut butter for ham sandwiches, negotiate playdates and Friday-night meet-ups, and collect votes for student council electionsand we forged friendships with as much noise as we could muster. Rob also came out of American schools, and I gather he had trouble imagining his own son being subjected to silence over salami (or, in this case, soybeans).

Cultivating a superstar student in China, Id come to learn, started with impulse control at the earliest age. Jammed into rows alongside his twenty-seven Chinese classmates, planted in a miniature chair, my son had learned to arrange each hand on its corresponding knee, back erect and feet positioned in parallel. He learned never to squirm in his seat or allow a foot out of place, for there was no faster way to draw a teachers ire. He understood he shouldnt ever touch the student next to him, talk when the teacher is talking, or stand up for water without permission. Above all, he learned the last thing he wanted was to draw attention to himself.

The red star was his reward for sitting mute in a chair, and my son proved a stellar trainee. Though Raineys toddler talk came out in halting sentences, at home he was clear about communicating one thing: The sticker would not be removed. Rainey brandished the red star at the dinner table, forehead tilted proudly toward the ceiling. He wore it during soccer practice and at a classmates birthday party. He even refused to peel it off when I tried to wash his face.

No, Momdont touch, dont touch! hed yelp, as we readied for bedtime. Off to bed he marched, red sticker intact.

Were we unwittingly engaged in a battle over our sons mind?

Should we be concerned? I found myself saying out loud.

Dont worry about it, my husband would respond, though sometimes I saw his forehead furrow, too.

I couldnt help but worry. Strolling through my Shanghai neighborhood, I observed Chinese children who were proper in public, polite to elders and peers, and orderly on the playground. I sauntered past the neighborhood elementary school at three p.m. on weekdays to see parents and grandparents waiting patiently in a pickup line that snaked around the block: Education here is a family affair. It was no stretch to imagine these children growing up to be disciplined geniuses, respected the world over. But what, if anything, were they giving up?

A journalistic curiosity kicked in as I began to seek answersby watching closely, asking the right questions, and pursuing experts with more knowledge than I had. As a daily reporter in New York, Minnesota, and California, Id always defaulted to this approach, and although Chinese society seemed to frown upon independent inquiry, I was driven by a powerful motivating force: parental anxiety.