[HAVING OUR SAY]

2012 Amy Hill Hearth, 1999 Amy Hill Hearth, 1993 Amy Hill Hearth, Sarah Louise Delany and Annie Elizabeth Delany

All rights reserved.

CAUTION: "HAVING OUR SAY" is fully protected under the copyright laws of the United States of America and of all countries covered by the International Copyright Union (including the Dominion of Canada and the rest of the British Commonwealth), the Berne Convention, the Pan-American Copyright Convention and the Universal Copyright Convention as well as all countries with which the United States has reciprocal copyright relations. All rights, including excerpting, professional/amateur stage rights, motion picture, recitation, lecturing, public reading, radio broadcasting, television, video or sound recording, all other forms of mechanical or electronic reproduction, such as CD-ROM, CD-I, information storage and retrieval systems and photocopying, and the rights of translation into foreign languages, are strictly reserved.

Inquiries concerning rights should be addressed to:

William Morris Endeavor Entertainment, LLC

1325 Avenue of the Americas

New York, New York 10019

Attn: Kathleen Nishimoto

Photo credits:

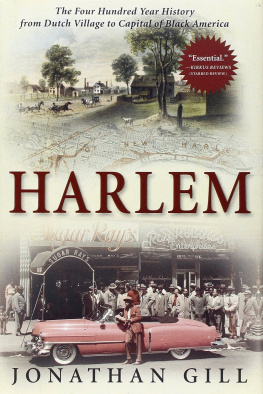

Photographs of the Delany Sisters as centenarians by Brian Douglas. Photograph of the Delany Sisters with Amy Hill Hearth by Blair A. Hearth. The Delany Sisters and Amy Hill Hearth gratefully acknowledge permission to reproduce the photograph of 135th Street and Seventh Avenue in 1930 from the Photographs and Prints Division of the Schomberg Center for Research in Black Culture, The New York Public Library Astor, Lenox and Tilden Foundations. All other photographs are from the Delany Sisters' private collection.

Acknowlegments:

The authors would like to thank Elisa Petrini, Milton R. Bass, Harry Henderson, Dr. James A. Boyer, Ron Mitchell, Helena Franklin, Minato Asakawa, Paul DeAngelis, Gillian Jolis, and Daniel A. Strone for their tremendous enthusiasm and support for this project. In addition, Amy Hill Hearth would like to thank her editors at The New York Times, Wendy Sclight and Roland F. Miller, for publishing her original article on the Delany Sisters ("Two Maiden Ladies With Stories to Tell," The New York Times, Sunday, Sept. 22, 1991.)

ebook ISBN: 978-0-7867-5554-7

Distributed by Argo Navis Author Services

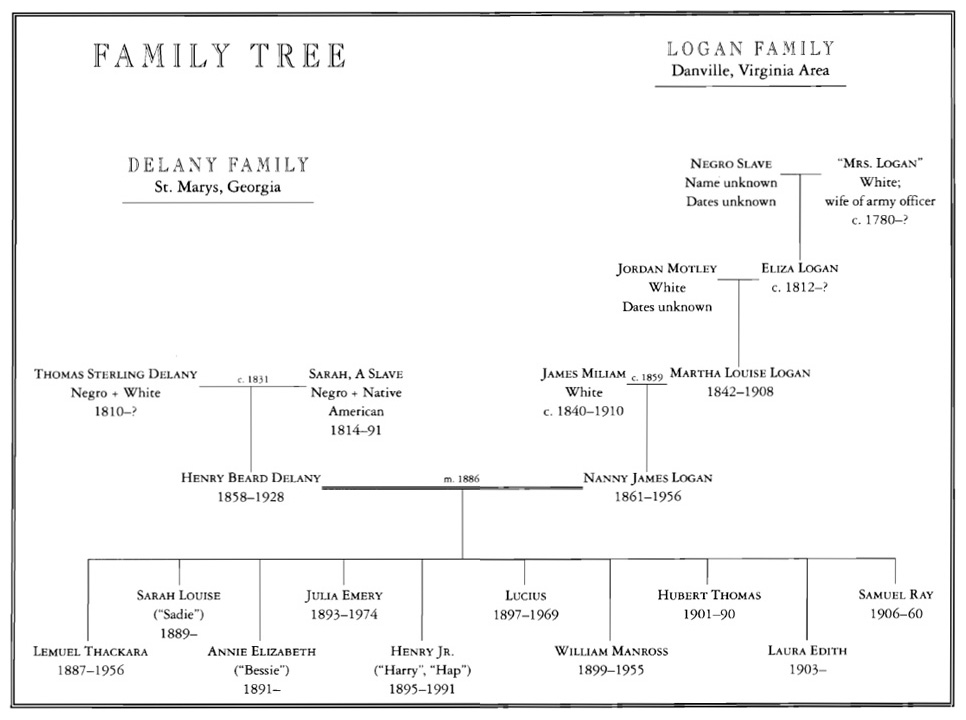

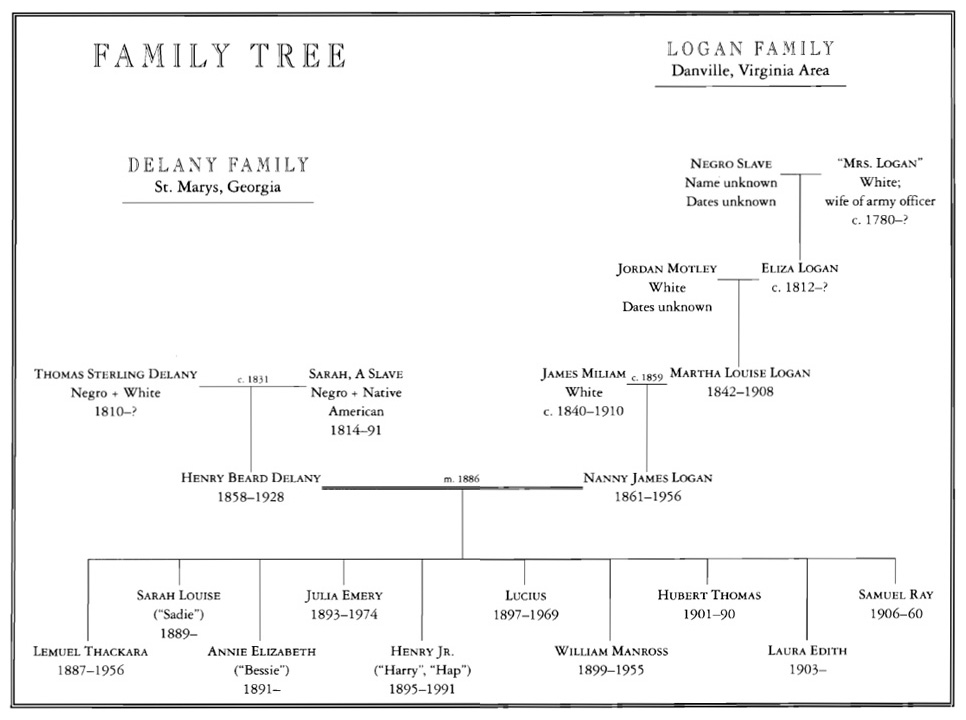

DEDICATED TO

HENRY BEARD DELANY (1858 - 1928)

and

NANNY LOGAN DELANY (1861 - 1956)

and to

BLAIR A. T. HEARTH

PREFACE

When I met Sadie Delany and her sister, Bessie, in September 1991, I was on assignment for The New York Times, hoping to write a story on these two elderly but reclusive sisters who had just celebrated their one-hundred-and-second and one-hundredth birthdays. In my hand I carried a letter written by their neighbor in Mount Vernon, New York, who had extended an invitation to come by and meet them. The Delany sisters had no phone, so I wasn't entirely sure they knew I was coming. I was prepared to be turned away.

I knocked on the door. I waited and raised my hand to knock again, when suddenly the door swung open. The woman who answered, with her head held high, her eyes intense and penetrating, extended her hand in formal greeting. "I am Dr. Delany," she said elegantly.

She ushered me into the house, and from across the room, another elderly woman said sweetly, "Please come in, child. Won't you sit down?" This was the elder sister, Sadie Delany.

I must have hesitated for a moment. "Go on, sit down," Bessie urged. "Sit down as long as you like. We won't charge you rent!" Then they both laughed uproariously at this little joke.

Over the next three hours, I was charmed by their vivaciousness and playfulness. They seemed to have conquered old age, or to have come as close to it as anyone ever will. It was clear that they had found the source of their vitality in each other's company, and in the tales they told and retold each other from a century of living.

When my piece was published, the reaction was swift. Readers fell in love with the Delany sisters. There were letters from all over the country, demands for television interviews, requests for guest appearances at schools and at political functions. The sisters declined nearly all of the invitations.

Among those who read my article were editors at Kodansha America, Inc., who felt that the Delanys' story deserved to be a book. At first the sisters demurred, unsure that their life stories were sufficiently interesting or significant. But they came to see that by recording their story, they were participating in a tradition as old as time: the passing of knowledge and experience from one generation to the next.

The daughters of a man born into slavery and a mother of mixed racial parentage who was born free, the sisters recall what it meant to be "colored" children in the late nineteenth century in the South. Their early lives were sheltered: They grew up on a college campus, Saint Augustine's School in Raleigh, North Carolina, where their father was an Episcopal priest and vice principal. Despite their privileged status, they suffered the insult of Jim Crow when it first became law.

After years of teaching in the rural South to raise money, the Delany sisters joined the great wave of black Americans who headed north in search of opportunity during the early part of this century. Bessie became only the second black woman licensed to practice dentistry in New York, and Sadie was the first black person ever to teach domestic science on the high school level in New York City public schools.

The sisters lived in Harlem, and were acquainted with such legendary figures as the statesman and poet James Weldon Johnson and the entertainer Cab Calloway. During an era when hearth and home defined the place of women, the Delany sisters spurned marriage opportunities for careers. In the 1950s they were in the vanguard of middle-class black Americans who integrated the suburbs and faced a new and difficult set of challenges. Already elderly in the 1960s, they cheered from the sidelines as the civil rights movement flourished, praying and worrying about younger relatives who were getting caught up in the protests.

Each sister developed her own way of coping within a racist society. Sadie expertly "played dumb" and manipulated the system, and Bessie believed in confrontation, regardless of the cost. This difference in personal styles has brought balance and occasionally fireworks to their hundred year companionship. "We are living proof that you don't change one bit from cradle to grave," Bessie likes to say.

This book is woven from thousands of anecdotes that I coaxed from the Delany sisters during an eighteen-month period (September 1991 to April 1993). The sequence of stories is mine but the words are all theirs. At times the sisters' versions of particular events were almost identical or told in a joint fashion with one sister beginning a sentence, and the other finishing it and so some chapters bear both of their names. In the others, either Sadie or Bessie chronicles their life together, each with her own distinct spin, voice, and viewpoint. Their story, as the Delany sisters like to say, is not meant as "black" or "women's" history, but American history. It belongs to all of us.