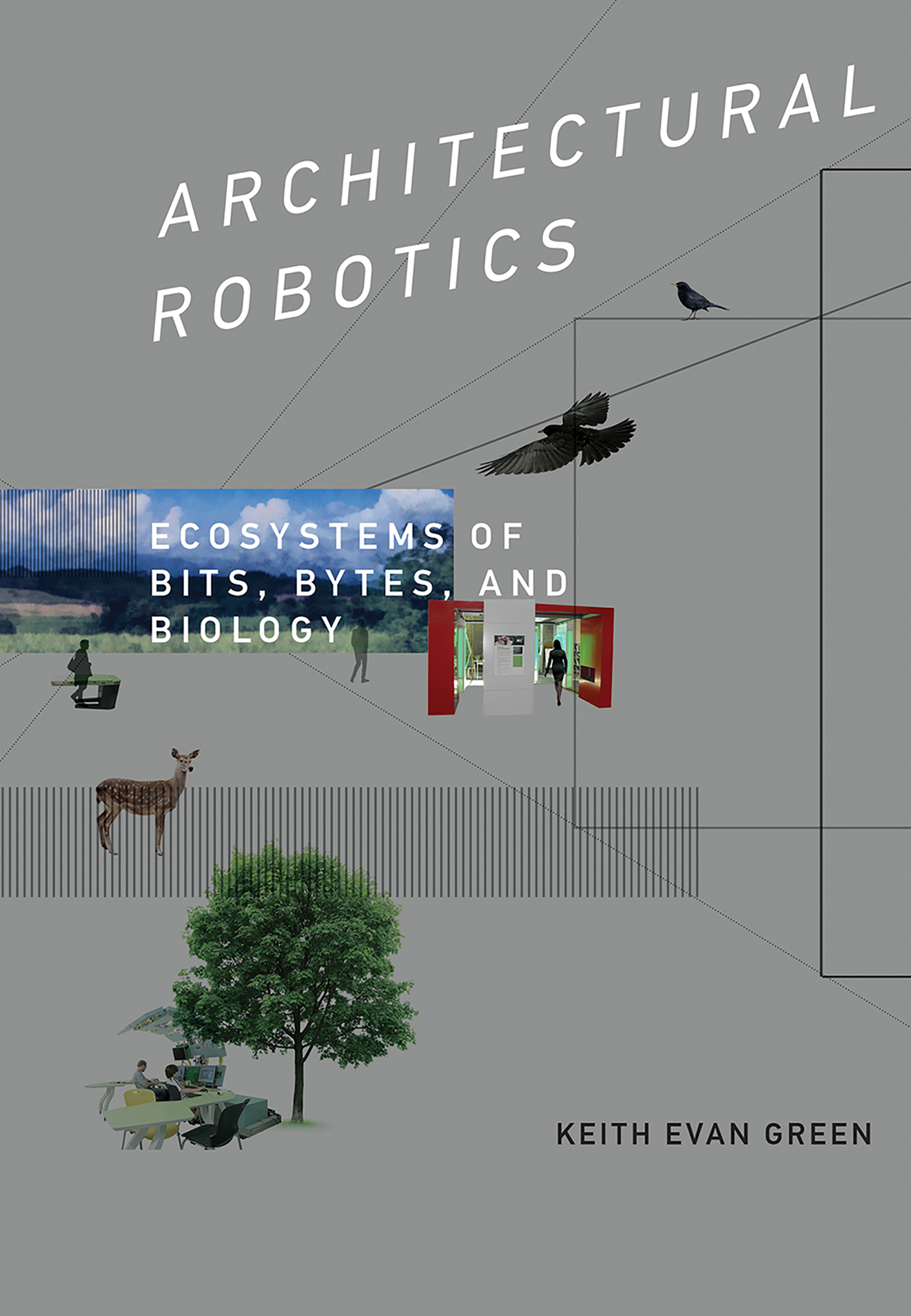

Architectural Robotics

Ecosystems of Bits, Bytes, and Biology

Keith Evan Green

The MIT Press

Cambridge, Massachusetts

London, England

No one can predict what environments architecture will create. It satisfies old needs and begets new ones.

Henri Focillon, The Life of Forms in Art , 1934

We believe its technology married with the humanities that yields us the results that make the heart sing.

Steve Jobs, launch of iPad 2, San Francisco, March 2, 2011

2016 Massachusetts Institute of Technology

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any

form by any electronic or mechanical means (including photocopying,

recording, or information storage and retrieval) without permission

in writing from the publisher.

This book was set in PF Din Pro by The MIT Press. Printed and bound

in the United States of America.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Green, Keith Evan, author.

Title: Architectural robotics : ecosystems of bits,

bytes, and biology /

Keith Evan Green.

Description: Cambridge, MA : The MIT Press, 2016. | Includes bibliographical

references and index.

Identifiers: LCCN 2015037895 | ISBN 9780262033954 (hardcover : alk. paper)

Subjects: LCSH: Architecture and technology. | ArchitectureHuman factors. | Cooperating objects (Computer systems) | RoboticsHuman factors. | BuildingsEnvironmental engineering. | Smart materials in architecture. | Intelligent buildings.

Classification: LCC NA2543.T43 G69 2016 | DDC 720/.47dc23

LC record available at http://lccn.loc.gov/2015037895

ePub Version 1.0

Contents

Preface

This book is not about architecture or computing but architecture and computing, which might prove frustrating or at least disappointing to some readers who were seeking more attention to and validation of their own disciplines and practices. My 9-year-old twin children, Maya and Alex, girl and boy, know this disappointment and frustration far better than I do, and as the parent to both them and this book, I am acutely aware, the moment I attend to one, that I have left the other out of the conversation. Or, at least, I partly fail to keep them both at hand, doing my best to speak to both at once.

Architecture encompasses everything, wrote Italian architect Gi Ponti. This is my challenge in writing this book. While architectural robotics is a narrow field of consideration, and while the body of work elaborated and otherwise referenced in these pages is in its infancy, the reach of this book is expansive: from architecture and robotics and human-computer interaction to the fine arts, philosophy, interaction design, industrial design and engineering, anthropology, education, medicine, psychology, cognitive science, and neuroscience. My formal education, life experiences, and street smarts get me through, but across these many pages I surely enter territory where Im more stranger than native. Please accompany me here, recognizing my intention is to grapple with a different way of thinking about, designing, and engaging some hybrid of architecture and computing.

Clearly, the subfield of architectural robotics is rapidly emerging, as observed in the addition of new academic programs and researchers concerned with it and in the entry of industry and venture capital into the domain of smart products, intelligent building systems, and assistive robotics. Its difficult to tell whether this book comes too early or too late, but I hope that, more than anything else, it has an influence on the way designers, defined in the broadest sense, view our world of physical bits, bytes, and biology and imagine making a contribution to it.

Acknowledgments

Many thanks are due:

to Henriette Bier, Kas Oosterhuis, and their Hyperbody Research Group at the Technical University of Delft (TU Delft) and to Tomasz Jaskiewicz, Pieter Jan Stappers, and their ID-StudioLab, also at TU Delft, for providing me with a commodious place in the Netherlands to write much of this book.

to Imre Horvth at TU Delft for energizing conversation and debate at the beginning and end of this process.

to Ufuk Ersoy, Robert Benedict, Yixiao Wang, and many others at Clemson University, and to its College of Architecture, Arts & Humanities for supporting this book.

to Mark D. Gross, director of the ATLAS Institute of the University of Colorado, Boulder, who collaborated with me on preparatory phases for this book, and who became a quiet, propelling force.

to my family, who put up with me during another long haul.

to the U . S . National Science Foundation for supporting each of the three case studies of this book, and especially to Ephraim Glinert, NSF program director, for his guidance and belief in an architectural robotics future.

to my Clemson graduate students and colleagues who made one of the three case studies of this book the primary focus of their research for several years, which qualifies each of them as a coauthor: Henrique Houayek, Martha Kwoka, Lee Gugerty, and Jim Witte ( AWE ); Tony Threatt, Jessica Merino, Paul Yanik, and Johnell Brooks ( ART ); George Schafer, Amith Vijaykumar, and Susan King Fullerton ( LIT ROOM / LIT KIT )

to, especially, Ian D. Walker, professor of electrical and computer engineering, who was my research partner for all three case studies, who graciously edited the technical parts of this manuscript, and who continues to realize with me the ecosystems of architectural robotics.

Chapter 1

Scenes from a Marriage

Consider, from a skeptical distance, the scene evoked by the term human-computer interaction as if it were a play being performed in a theater. We have an empty stage but for a desk and a desk chair, both of no particular qualities. The lighting is nondescript. On the desk is a desktop computer, probably an IBM . (Is it a ?) And seated before the computer, the human. The monitor of the computer is positioned at eye level of its user. The physical size of the computer appears to be not much larger than the size of the humans head, so that the human and the computer appear as intimates.

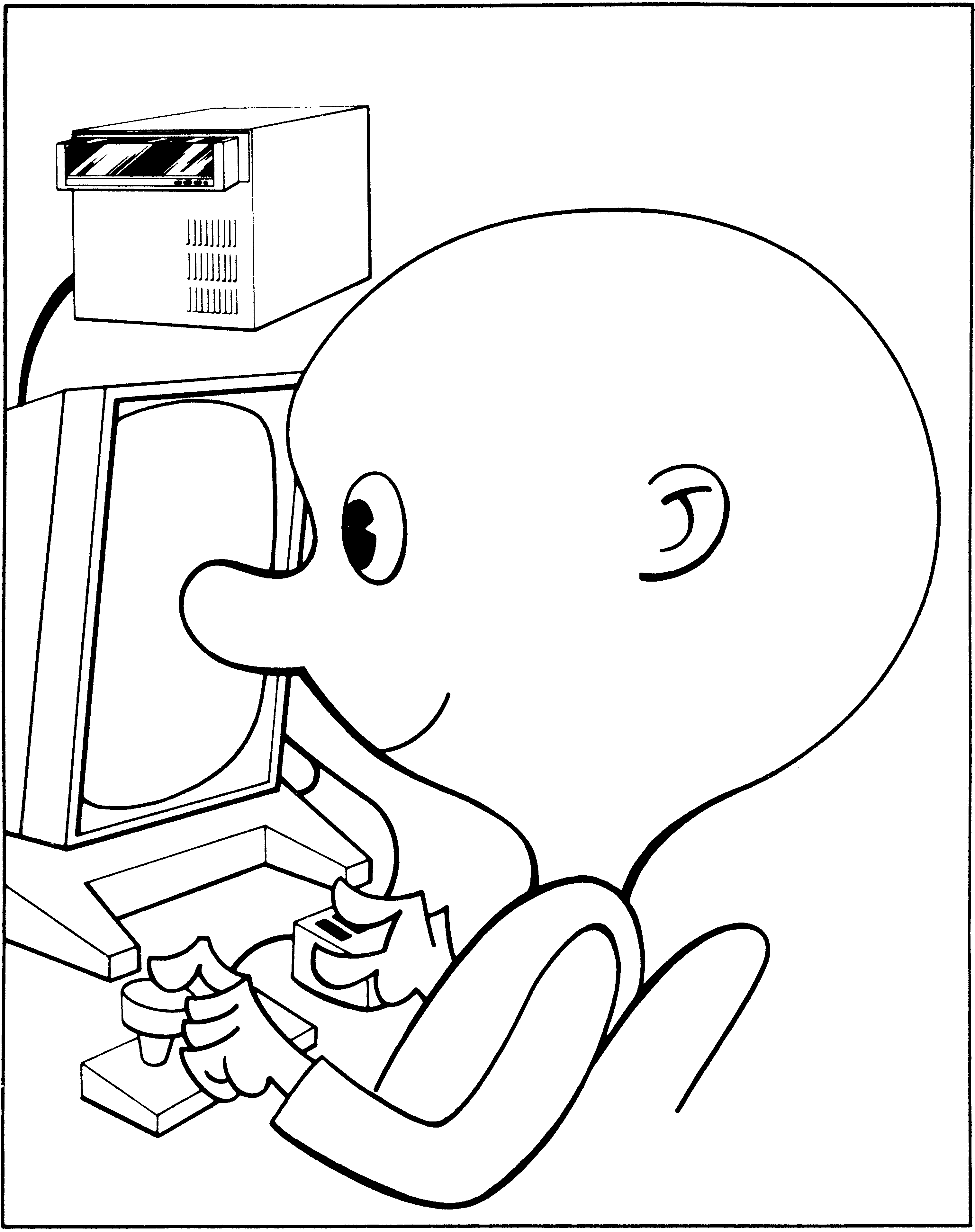

This is scene 1 of human-computer interaction, set in 1983, as portrayed in The Psychology of Human-Computer Interaction , the book that popularized the term human-computer interaction (or HCI , for short). , a bubble-headed human, happily and without distraction, commands a CPU connected to the television-like computer display that was typical of its day. So engrossed is the merry human in his interactions with the desktop computer that he remains oblivious to the fact that his nose is practically one with the display (and may even be polishing it!). Observe, as well, that our bubble-headed friend is seemingly no more than a head and upper torso sharing a vacuous space with the computer. The desk chair in this scene is only signified. The desk and stage are absent altogether.

Figure 1.1

Scene 1: One human and one computer (from The Psychology of Human-Computer Interaction , reprinted with permission of Taylor & Francis).

This scene 1 of human-computer interaction can hardly portray our engagement with computing in the new millennium. In scene 2, which begins in 2007 with the introduction of the iPhone, computing finds its way into our pockets, our cars, our appliances, into our everyday lives, indoors and out. This is ubiquitous computing , the kind of computing that is all around us, woven into the fabric of everyday life, now that computer hardware is cheaper and more powerful, more miniaturized, more readily available, and more accessible to so many more of us.