Acknowledgments

H ow far back do you go to acknowledge and thank those for the support and encouragement you have received in recognition of where you are today? It is a long chain of connections and associations that brings one to her current place.

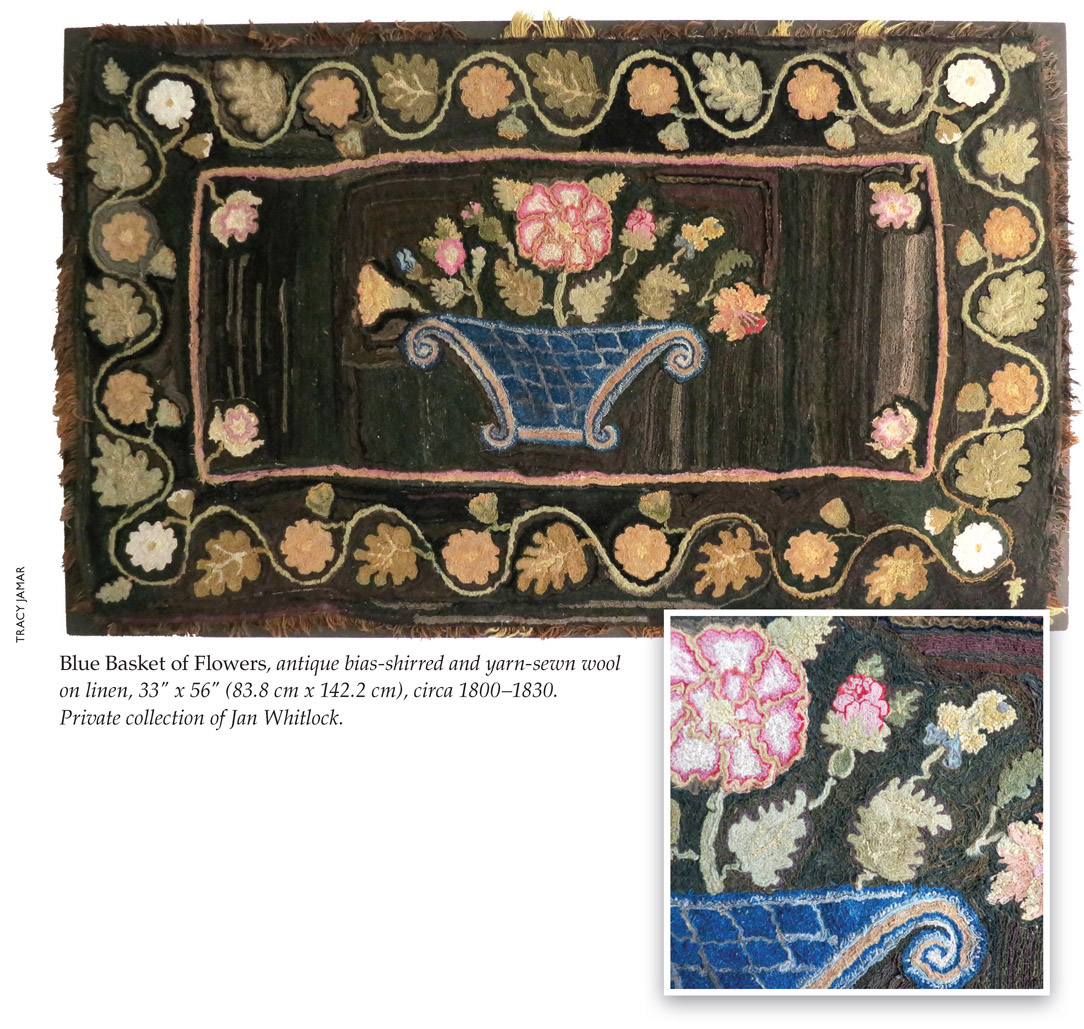

To parents who were doers and makers in their own right as models. To friends along the way with mutual appreciation and encouragement. To a broken relationship that propelled me to NYC, where Kate and Joel Kopp offered me a job at America Hurrah Gallery. It was there I was immersed in exposure to and restoration of the finest in antique American textiles. To Jan Whitlock, not only for trusting me with her exceptional textile projects and inviting me to take part in her book idea, which inspired this book, but to a friendship as well. To Debra Smith, editor of Rug Hooking Magazine, for the offer of writing this book, which has expanded my creative world in many wonderful ways. To the community of fiber folks who inspire, share, and challenge each other to experiment and explore new things. To my husband, Monty Silver, for his appreciation and encouragement in my fiber pursuits and for his patience and well-tested tolerance in allowing me to spread my projects (almost) everywhere.

Thank you all!

CHAPTER 1

Antique Rug History and Techniques

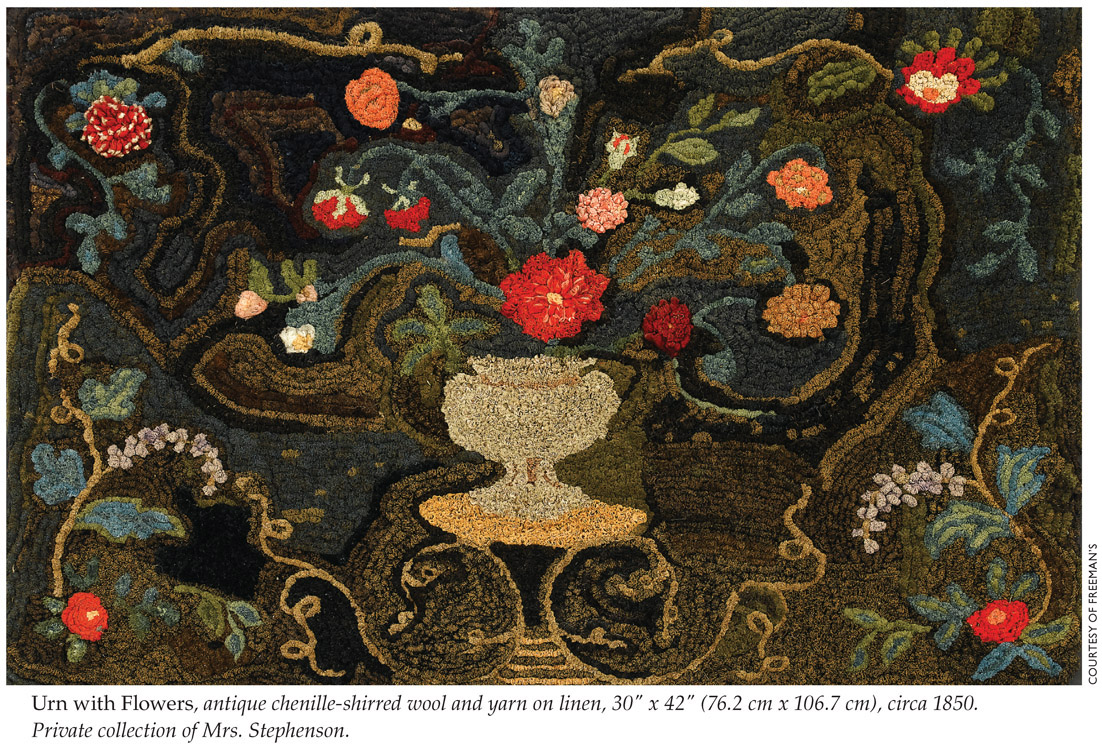

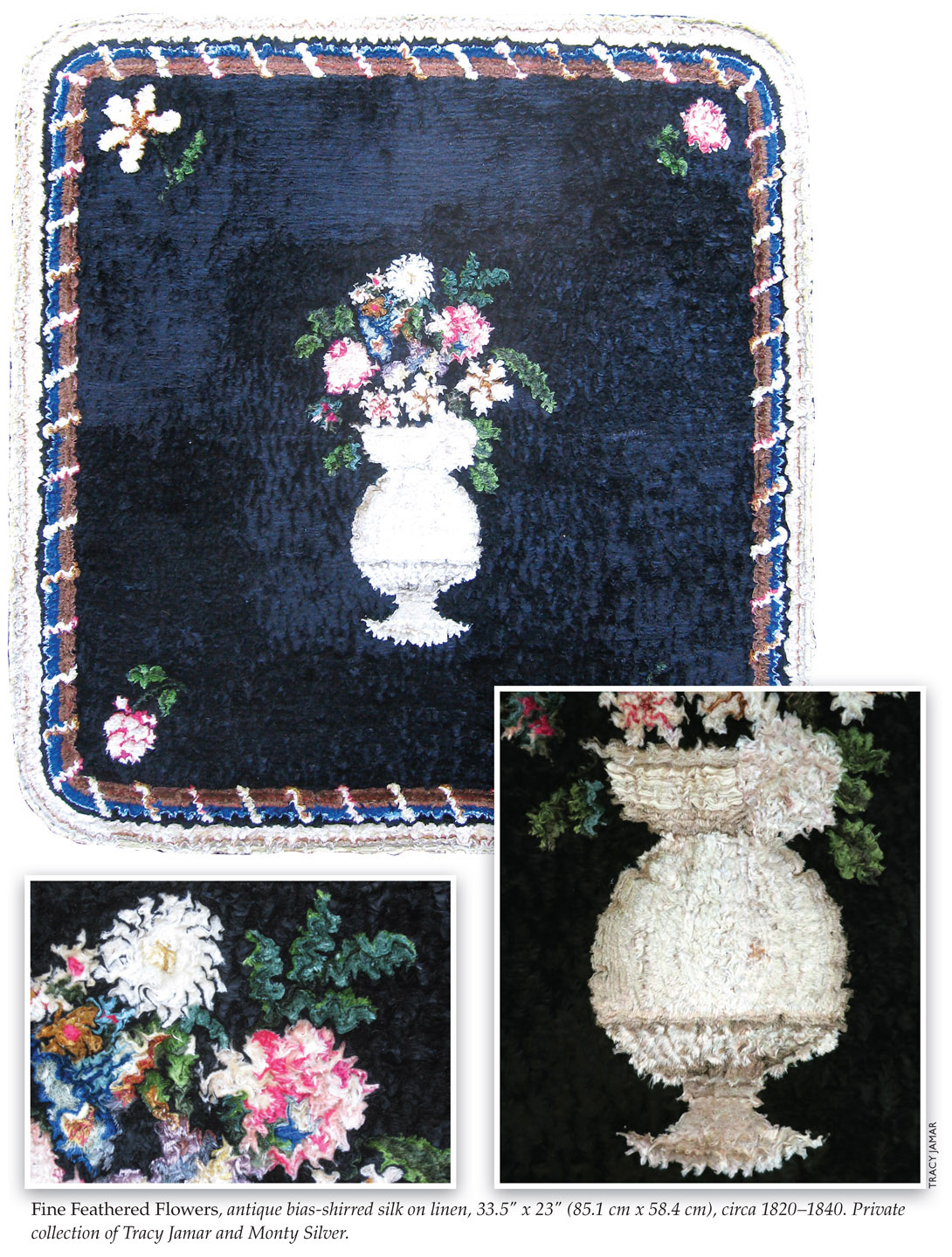

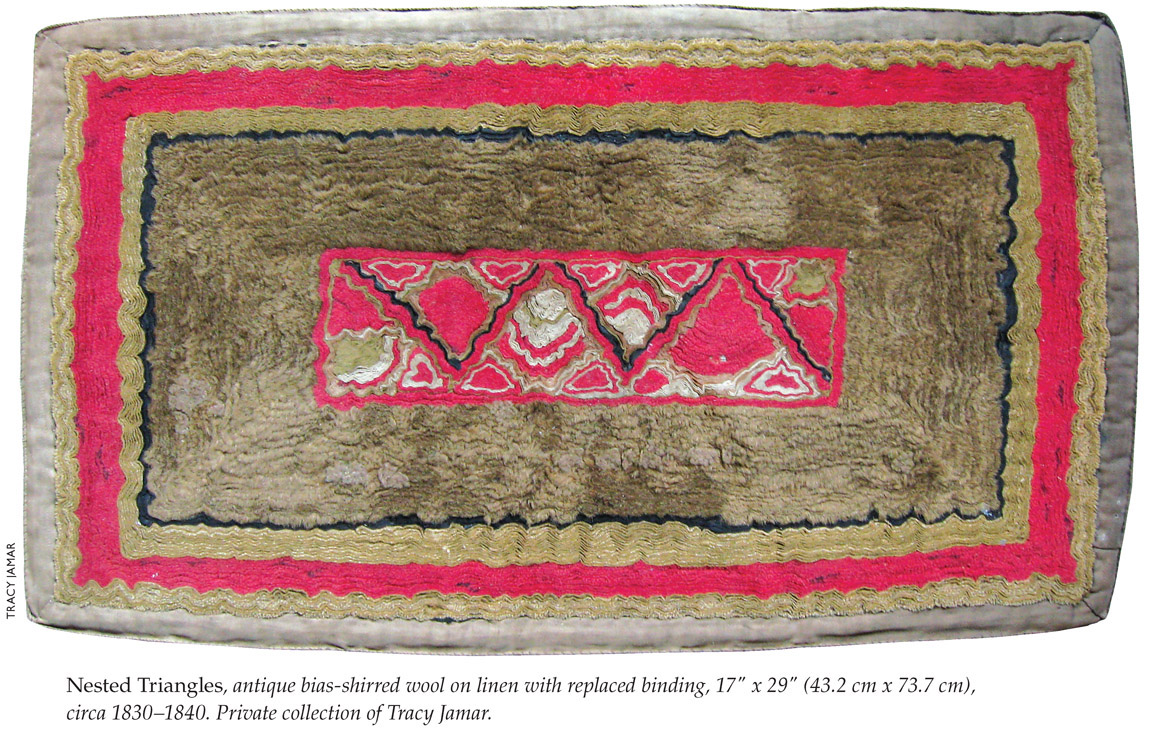

I n the early nineteenth century, many handmade rugs were created with a variety of techniquesseveral shirring variations as well as yarn-sewn, patched, and appliqud rugs are from that period. These early handmade rugs were regarded as showpieces of handwork, not just utilitarian household objects. Making these rugs required skill, time, and material; at least two of those were not available to any but the wealthiest.

Though not nearly as well documented as samplers of the same era have been, some of these early rug-making techniques were taught at schools for girls from well-to-do families. Originating as an upper-class enterprise, these rug-making forms became nearly obsolete after the mid-nineteenth century. At that time more and more manufactured goods became available to a rising middle class. Styles changed and women across the economic spectrum were able to buy more of that which they once had to make themselves.

Technological improvements in all forms of manufacturingespecially textile productionallowed fabrics to be made more inexpensively. That, along with the greater availability of burlap, allowed women from lower economic levels to find rug hooking to be a perfect form to express themselves and provide an inexpensive way to decorate their homes. Rug hooking was also, not inconsequentially, markedly quicker to do when compared to the various forms of shirring.

As this nineteenth-century Canadian rhyme suggests, rug hooking became associated with old, worn, reused clothing and a make do, waste not attitude.

................................

I am the family wardrobe, best and worst Of all our generations, from the first: Grandpas Sunday-go-to-meetin coat, and the woolen muffler he wore at his throat;

Grandmas shawl, that came from Fayal;

Mas wedding gown, Three times turned and once let down, Which once was plum but now turned brown;

Pas red flannels that made him itch;

Pants and shirts;

Petticoats and skirts;

From one to the other, but I cant tell which. Tread carefully, Because, you see, If you scuff on me;

You scratch the bark of the family tree.

................................

Although the economic and societal changes of the time augured the near loss of those earlier rug-making forms and heralded the rise of rug hooking, the shirred techniques offer some of the most interesting and textural effects that can be incorporated into contemporary hooked pieces and other fiber art.

Shirring

Shirring refers to techniques used in the making of hand-sewn rugs, most created between 1820 and 1850. These rugs were made from material that was fashioned and manipulated in a number of ways and then sewn to a foundation. There are several variations of shirring: bias, chenille, bundled, fringed, and pleated. The first two are made with narrow strips of fabric that are gathered (slightly with bias, more fully with chenille) and sewn to a foundation.

One of the other variations is one Jan Whitlock and I labeled bundled in our book American Sewn Rugs: Their History with Exceptional Examples. These rugs were made using short, narrow strips of fabric or short lengths of yarn that are tied up in little bundles and/or small pieces of fabric, such as circles or squares, that are folded, secured, and then sewn to a foundation. The fringed version is made with strips of fabric folded lengthwise, clipped perpendicular to the length to create fringe, and then sewn to a foundation. There are also examples of rugs made with commercially made fringe that was attached to a foundation.

These forms of construction were dependent on a thread securing the decorative elements to a fairly sturdy foundation, which meant they were not as durable to heavy use as a woven or pile rug would be. We ascertained that they were more commonly used for decorative purposes or in areas of minimal use.

Standing Wool

Whereas wealthier households were more likely to have shirred rug examples, standing wool seems to have been popularized by folks of more modest means. The makers used worn-out clothing or fabric leftovers to create allover patterns for their rugs and mats. How far back the form goes would be hard to ascertain, as it is likely that these rugs, a variant of rag rugs, were used in a more utilitarian manner than the fancier shirred examples, and therefore fewer of them have survived.

Standing wool uses strips of fabric that are manipulated in folds, coils, and gathers and then sewn to each other. These strips can be used singly, in multiple layers sewn as one, or made extra wide and folded in half lengthwise (used with the fold up or down) before assembling and stitching them in a symmetrical radiating pattern or free-form design. As they are sewn with flat sides together, the edges of the strips become the visible surface of the rug.

As its name would suggest, standing wool is substantial enough to be its own support; often made without a foundation, it is therefore reversible. The name seems to be a contemporary descriptive term, and though the technique has been used for a long time, it too is gaining in popularity as a new technique.

Rugs can be made exclusively with the standing wool technique, but the form and its variations are being used more and more in conjunction with other techniques. The strips, single or folded, can be coiled as part of the design, used in undulating lines or switchback sections, wrapped around other elements, or worked as a single length or with another strip of a different color for interesting design purposes.