Prologue: Preliminary

Observations on Pie

I may not be able to define a pie, but I know one when I see it.

Raymond Sokolov

It behoves, I am told, every author to consider the scope of her work before launching into it. No problem, I thought. It is simple. It is about Pie. It is also, I am told, essential for the author to describe the scope of her work at its beginning, in order to forewarn her readers. Simple, I thought. I will start by defining Pie. In the end, I failed utterly. I would have agonized less over my failure had I remembered the above quotation rather earlier in the piece than I did. If the illustrious and erudite Raymond Sokolov cannot define pie, who am I even to attempt it? Nevertheless, I dont regret the attempt, as it was fascinating and enlightening in ways that I would not have suspected.

I began with a memory I had of a venison pie I once ordered at an upmarket restaurant. After exactly the right anticipatory interval my dinner arrived. It was very elegant. On a base of fluffy garlic mashed potatoes was a cleverly layered construction of julienned vegetables topped with slivers of tender, rare venison, the whole surmounted with a precariously balanced disc of puff pastry. It was delicious, but it was not pie. I was quite sure that it was not pie. Clearly, the chef and I had vastly differing opinions on the issue, which brought me to an early epiphany. When and if I came up with my concise, accurate definition of pie, not everyone else in the world would agree with it.

But surely there would be some areas of consensus as a starting point? Pies are not pies simply because they are called pies. The American treat called Eskimo pie, for example, is unequivocally ice cream, and moon pie is a chocolate biscuit with pretensions. Boston cream pie is certainly a cake, but apparently called pie because it is baked in a pie tin, by which logic I could cook porridge in a pie pan and call it porridge pie. Other pies are more problematic. Is a sausage roll a small pie? Should I include cobbler and pandowdy, which seem like failed pies with broken lids? Traditional Scottish black bun and English simnel cake are fruit cakes with pastry shells. Do they count? I pondered cottage pie and shepherds pie. These have a layered pie-like structure certainly, but were (to me) instantly definable as not real pies. Why not? Another epiphany dawned. Because they have no pastry. It seemed that my attempt at definition was devolving into a set of minimal criteria, at least for the purposes of this book. This second epiphany led to the First Law of Pies: No Pastry, No Pie.

For reasons which will become apparent in chapter One, I immediately came up with the Second Law of Pies: they must be baked, not fried (or boiled, or steamed). One more law as to the number and location of crusts required (single top, single bottom, or double), and my criteria would be set or so I thought. Formulating the Third Law of Pies proved to be an extraordinarily difficult part of the challenge, and I am still far from sure that I have resolved it in a satisfactory manner. I began my crust count with the Oxford English Dictionary, which asserts that a pie is:

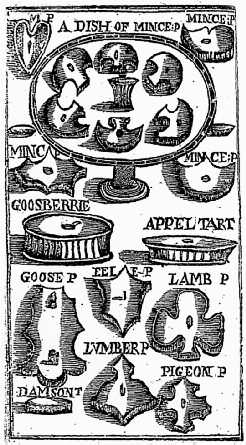

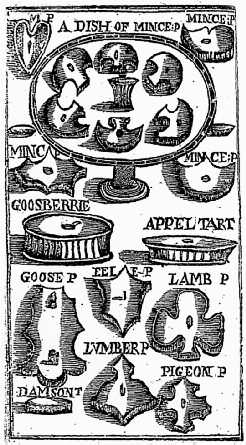

| Pie shapes, from The Queens Royal Cookery by T. Hall, 1713. |  |

A baked dish of fruit, meat, fish or vegetables, covered with pastry (or a similar substance) and freq. also having a base and sides of pastry. Also (chiefly N. Amer.): a baked open pastry case filled with fruit; a tart or flan.

It would seem then, that the editors of the Oxford English Dictionary are of the opinion that, to qualify as a pie, the top crust is essential and the bottom crust optional, except in America where it is the bottom crust that has primacy. They also appear to be suggesting that the bottom-crust American pie is, according to British-English usage, a tart or flan. The definition becomes less clear when they go on to describe a flan as an open tart, and a tart as the same, or nearly the same as a pie.

I, who love and revere the Oxford English Dictionary, have to admit that it displays a lack of clarity in respect of pies and tarts, as indeed does most of the English-speaking world. Nowhere has this been more passionately demonstrated than in an extraordinary debate in the correspondence pages of The Times in 1927. In September of that year, a Mr R. A. Walker was moved to write a letter of vigorous protest on the abominable soul-slaughtering and horrible trick of serving puff pastry and stewed fruit under the guise of apple tart, for which he blamed restaurateurs. Mr Walkers issue was to do with pie quality, but he was quickly taken to task by Colonel John C. Somerville for using apple pie and apple tart as alternatives. The Colonel could not for one moment allow this, remarking that all properly brought up children would know the difference. He went on to define pie as whatever is cooked in a pie dish under a pastry roof , whereas when the fruit lies exposed in a flat substratum of pastry, then, and only then, can it be rightly called a tart. A surprisingly passionate debate ensued over the next two weeks, with veiled insults and categorical statements being made and side issues being thrown in. Several expatriate American and French readers weighed in with their opinions and, as the discussion was becoming rather heated, an advocate of concise nomenclature appeared in the form of Professor Henry E. Armstrong. The professor heartily supported the discussion, and proceeded to give, as his best example, rice pie, always with an emphasis on pie. He described rice, with a due amount of sugar and a plentitude of farmhouse milk baked in a pie-dish; therefore a pie, the more because in the jargon of the scientific it is delicately auto-encrusted. He clarified that this dish was not pudding, because a pudding must be boiled in a cloth and have a crust, but without sign of brown. The professors academic field was not indicated, but his slightly pompous opinion precipitated an indignant response from Mr E. E. Newton, who called his expertise into question, declaring that he cannot be a professor of cookery. Mr Newton pointed out that the crust of the professors pie was simply the skin formed by the heat of the oven, whereas a pie has a crust formed of something different from the contents. Another offended correspondent asked the stickler how he would classify the famous Kentish pudding-pie with its substratum and deep vertical wall of pastry... filled to the brim with custard and cooked in a container in an oven and warned: If you want this dish in Kent, dont ask for custard tart.