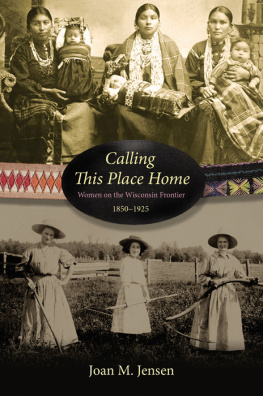

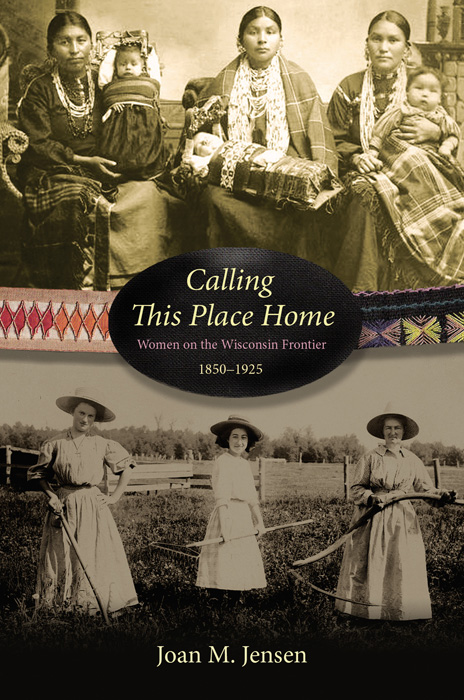

Calling This Place Home

Calling This Place Home

Women on the Wisconsin Frontier, 18501925

Joan M. Jensen

MINNESOTA HISTORICAL SOCIETY PRESS

Publication of this book was supported in part with funds provided by the Ken and Nina Rothchild Endowed Fund for Womens History

2006 by the Minnesota Historical Society. All rights reserved. No part of this book may be used or reproduced in any manner whatsoever without written permission except in the case of brief quotations embodied in critical articles and reviews. For information, write to the Minnesota Historical Society Press, 345 Kellogg Blvd. W., St. Paul, MN 55102-1906.

www.mhspress.org

The Minnesota Historical Society Press is a member of the Association of American University Presses.

Manufactured in the United States of America

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

A The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of the American National Standard for Information SciencesPermanence for Printed Library Materials, ANSI Z39.48-1984.

Sections of various chapters have appeared in different form in the following publications:

Out of Wisconsin: Country Daughters in the City, Minnesota History 59.2 (Summer 2004): 4861.

Id Rather be Dancing: Wisconsin Women Moving On, Frontiers 22.1 (2001): 120.

Sexuality on a Northern Frontier: The Gendering and Disciplining of Rural Wisconsin Women, 18501920, Agricultural History 73.2 (Spring 1999): 13667.

The Death of Rosa: Sexuality in Rural America, Agricultural History 67.4 (Fall 1993): 112.

International Standard Book Number 13: 978-0-87351-563-4 (cloth)

International Standard Book Number 10: 0-87351-563-3 (cloth)

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Jensen, Joan M.

Calling this place home : women on the Wisconsin frontier, 18501925 / Joan M. Jensen.

p. cm.

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN-13: 978-0-87351-563-4 (cloth : alk. paper)

ISBN-10: 0-87351-563-3 (cloth : alk. paper)

E-book ISBN: 9-780-87351-728-7

1. WomenWisconsinHistory.

2. WomenWisconsinSocial conditions.

3. WisconsinHistory19th century.

4. WisconsinHistory20th century.

I. Title.

HQ1438.W5J46 2006

305.40977509034dc22 2006002282

For Mary Ann Reynolds

Family Archivist and Storyteller

Table of Contents

Preface

Many people have helped with this long project. Any list would be only a partial recognition of those who offered support, encouragement, and bits of information to add to the mosaic. Relatives, friends, archivists, librarians, strangers who responded to e-mail and letter all made this a richer and fuller account than I could have composed alone.

I also thank the institutions that partially funded this project over the years. New Mexico State University gave me much-needed time away from teaching with sabbaticals and summer grants. In spring 1988 I received a Senior Fulbright Fellowship that allowed me to teach and to study immigrant history with Dirk Hoerder and Christiane Harzig at the University of Bremen. The National Endowment for the Humanities offered me early support with a Summer Grant in 1989 and a Travel to Collections Grant in 1990. The New Mexico Endowment for the Humanities helped with a Summer Grant in 1994. In 1995, when I realized that Native women had to play a larger part in my story, Peter Iverson generously invited me to sit in on his Native History graduate seminar at Arizona State University, and the Newberry Library offered me a fellowship to catch up on recent Native American history. Finally, a research grant in 2001 from the Minnesota Historical Society allowed me to trace the lives of some of these Wisconsin women in the Twin Cities.

A few people were key in helping me nish this long project. Monica Torres, who fteen years ago helped me conceptualize Loosening the Bonds: Mid-Atlantic Farm Women, 18501950, moved back to Las Cruces just in time to assist me in organizing the nal draft of this second regional study of rural women. With amazing patience, Karen Lerner helped me sort out fteen years of footnotes. My partner John Gustinis read the manuscript, offered me a rst edit, cooked, cleaned, and took me on afternoon bird-watching walks to lift my agging spirits. At the Minnesota Historical Society, Debbie Miller, Ann Regan, and Anne Kaplan continued to encourage my work on rural women as they have over the years. The enthusiasm of my editor, Wisconsin-born Shannon Pennefeather, carried me through the last trying months of revision. Members of the Rural Womens Studies Association (rwsa) were a constant source of inspiration for the larger task of writing rural women into history. Most importantly, my cousin Mary Ann Reynolds never wavered in her conviction that the history of the people of this region was important and that trying to understand it was a worthwhile task. This book is dedicated to her. I hope that this study will open the landscape of north-central Wisconsin to continued study by those whose lives it has touched.

Introduction

Most of the events in this book take place in northern central Wisconsin. Described in the early nineteenth century by eastern Euro-Americans as a part of the Old Northwest or even the Far West, it became in the late nineteenth century the West and then part of the Midwest. Euro-Americans spread westward from eastern states and south from what is now Canada. So too did a number of Native groups. Europeans immigrated from all directions. By 1850, the people of many cultures called this place home. To Native peoples already there, it was their homeland.

Settler families there participated actively in the Civil War: husbands and sons went off to the battlefront; women and older men farmed and supported the Union cause from the home front. After the war, farm families settled the southeastern area of the state rapidly. In north-central Wisconsin in 1860, however, only a sprinkling of non-Native settlements existed. Much of the land was only marginal for farming. On this northern frontier, Natives and settlers still jostled for space to live. They experienced the transition from a fur-trading to a lumbering economy, and as that latter economy waned at the turn of the century, all people scrambled for economic alternatives. This northern Wisconsin frontier was similar to that west of the Mississippi during the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. Both frontiers shared common characteristics: a swift and ruthless exploitation and destruction of natural resources, settlement by non-Native peoples, enclosure and containment of Native communities in circumscribed areas which the national government attempted to control.

Wisconsin has long been the locale of a search for theories about the settlement process. When in the early twentieth century Frederick Jackson Turner imagined the frontier as a process of settlement that inuenced national character, he was living in and looking back at his youth in Wisconsin. To some extent, his theories inscribed the early peopling of southern Wisconsin by Euro-Americans. He envisioned a frontier moving west across the country under the impetus of white men while white women were subsumed under the term family. In his theory, indigenous Native peoples were quickly replaced by pioneers.