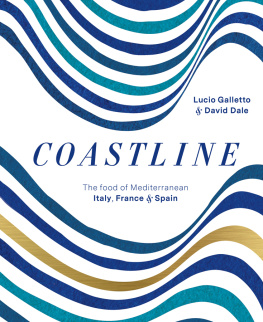

The perfect pesto.

The best bouillabaisse.

The purest paella.

A river of gold flows through western Italy, southern France and eastern Spain. Its the olive oil that links three great cuisines, along with a love of garlic, anchovies, peppers, fresh herbs and seasonal vegetables. In stories and recipes, and beautiful location photography, Coastline explores the legacy of the ancient Greeks, the Romans, the Arabs and the Vikings, who left the gift of a cuisine of the sun flavoured with generosity and conviviality.

Catalans call them seitons (say-tons), Provenals call them anchois (ansh-wa), Ligurians call them acciughe (achoo-geh). For 4000 years anchovies have been a core ingredient in the cuisine of the sun.

Contents

About the authors

LUCIO GALLETTO

Lucio Galletto was born on the border of Liguria and Tuscany in north-western Italy, where his family had opened a restaurant in the fishing village of Bocca di Magra. He was working as a waiter there and studying architecture when he fell in love with a passing Australian backpacker and decided to move to Sydney. Over three decades, his art-filled restaurant, Lucios, has won numerous awards, and in 2008 he received the Medal of the Order of Australia for service to the community through contributions as a restaurateur and author, and to the support of arts organisations. His books include The Art of Traditional Italian ; and, co-written with David Dale, The Art of Pasta, Lucios Ligurian Kitchen and Soffritto: A Delicious Ligurian Memoir .

DAVID DALE

David Dale is a writer and broadcaster on travel, food, popular culture and anthropology. He trained as a psychologist but decided he would do less harm to the cause of mental health if he went into journalism. He has been a reporter, feature writer, foreign correspondent and editor for all of Australias major media organisations and his 14 books include Anatolia: Adventures in Turkish Cooking ; The 100 Things Everyone Needs to Know about Italy ; Essential Places: A book about ideas and where they started ; The Little Book of Australia ; and The Obsessive Traveller: Or why I dont steal towels from great hotels any more . He teaches journalism at The University of Technology, Sydney.

COLLIOURE (FRENCH CATALUNYA): The lanes near the beach are lined with tiny food shops.

Davids introduction

When I suggested this project to Lucio Galletto, he reflected for a couple of seconds and said: Yes, that should be okay. Paella is just burnt risotto, isnt it?

H e was joking, of course, as he often is. He might equally have said Bouillabaisse is just zuppa di pesce with toast on top, or Ratatouille is just undercooked samfaina , or Pistou is just pesto without cheese. He got my notion immediately that the various cuisines of the western Mediterranean are really branches of a single olive tree that was planted 2600 years ago by the Greeks, and fertilised by the Romans and the Arabs, and we ought to get a useful book out of exploring how the cuisines overlap. At the very least, it was a great excuse for a road trip through some of Europes liveliest cooking, warmest communities and most spectacular seascapes.

All Lucio would have to do was construct a bunch of recipes based on our experiences in Catalunya, Provence and Liguria, while I gathered the stories and tasted the food. Lucio was amused by my theory that, as a descendant of the Liguri tribe which once controlled the coastline between what is now Barcelona and what is now Carrara, he was in a unique position to help me chronicle how his tribes eating habits have evolved over three millennia.

This book had been germinating in my head for about 30 years, ever since I read a remark by the American food scholar Waverley Root in The Food of France . Root said the national boundaries within modern Europe make no sense: they force disparate peoples into artificial alliances and split once cohesive cultures along borders created by accidents of war and diplomacy. He suggested it would be more logical to segregate Europeans by their preferred cooking medium: into The Domain of Butter, The Domain of Lard and The Domain of Olive Oil. The Domain of Butter would include most of France, Belgium, Switzerland and the Netherlands. The Domain of Lard would include most of Germany, Scandinavia, the nations that used to be Yugoslavia, and a pocket of north-eastern Italy. The Domain of Oil would include southern France, most of Spain, and most of Italy and Greece.

Since I embraced the logic of Roots new European borders, most of my travelling, cooking and eating has been through The Domain of Oil. It became apparent that the citizens of Valencia (Spain) have more in common with the citizens of Collioure (France) than with the citizens of Madrid; the residents of the Cinque Terre (Italy) have more in common with the residents of Nice (France) than with the residents of Rome; and the Marseillais have more in common with Catalans and Ligurians than with Parisians, despite having a national anthem named after them.

My deeper understanding of The Domain of Oil began in 2001, when I was in eastern Liguria researching a book (called Soffritto ) about the area where Lucio grew up. In 1950, Lucios father and uncle built a shack on a beach where the Magra River enters the sea, and started serving zuppa di pesce (fish stew) to the locals. They didnt know it, but they were replicating the behaviour of a bunch of Greek mariners who had bumped onto that shore 2600 years earlier.

Lucio grew up between the tables of the family restaurant, Capannina Ciccio, but at the age of 23 fell in love with an Australian backpacker and moved to Sydney, where he now runs one of Australias most awarded Italian restaurants. His cousin Mario still runs Capannina Ciccio, and still serves zuppa di pesce where the Magra enters the sea on the border of Tuscany and Liguria.

A few minutes drive from Marios place are the ruins of a Roman city called Luni. One morning, while Lucio and I were examining the ancient amphitheatre, we met a tour guide named Sara, who told us that 2000 years ago, this had been a marble city so magnificent that invading barbarians thought it was Rome. Although Luni is three kilometres inland nowadays, it was then a deep bay, described by the geographer Strabo in 10 AD as just such a place as would become the naval base of a people who were masters of so great a sea for so long a time, meaning the Romans.

Sara said she hated the Romans for what they had done to her people the Liguri tribe, who had been subjected to ethnic cleansing. Sara told us the Romans had launched the invasion of Hispania from their naval base at Luni, and had presumably done the same sort of ethnic cleansing on the Hispanics who had, up to then, lived harmoniously with the Greeks who set up trading posts on the Spanish shoreline.