One of the few surviving Istanbul street markets, in Kadky.

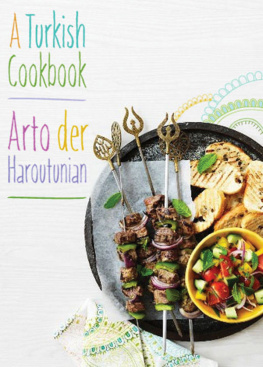

This book has two inspirations: Musa Dadeviren, who introduced regional Anatolian food to the world long before it was trendy; and Janni Kyritsis, great chef and great friend, who embodies the notion that generosity of spirit crosses all national boundaries.

Somer Sivriolu grew up in Istanbul and moved to Sydney when he was twenty-five. He now runs Efendy restaurant in Balmain where he draws on a multitude of cultural influences to recreate the food traditions of his homeland.

David Dale is an Australian political journalist, commentator on popular culture and food and travel writer. His earlier books include Soffritto: A Return to Italy ; The Art of Pasta (with Lucio Galletto); Essential Places ; and The Obsessive Traveller or Why I Dont Steal Towels from Great Hotels Anymore .

Fans of Galatasaray football team gather in Istanbuls meyhane district, before losing 61 to Real Madrid.

DAVIDS PREFACE

For a while I was keen to call this book The Garden of Eden , but my sensible co-author talked me out of it.

The idea came up when we were flying east from Istanbul and I was studying a map of our destinationthe town of Gaziantep near the Syrian border. I said to Somer: This river thats labelled Fratis that the Euphrates? He replied: Yes, thats the old name for it.

In growing excitement, I asked: Is the Tigris also on this map? Somer: Yes, just down there, its called the Dicle [dizh-leh] nowadays. Me: So actually we are headed for the Garden of Eden, where all the fruits and vegetables in the world originated, and where the forbidden apple was probably a fig? Somer (eyes narrowed): Well, I suppose you could say that.

One of the first things I learned about Somer Sivriolu (pronounced Sivriolu, with the g silent, as in tagliatelle) is that he prefers science to superstition, and hes inclined to regard references to Adam and Eve with caution. I share his scepticism, but I love a good story, particularly when its about food. I was charmed by the notion that Anatolian was the worlds oldest cuisine.

Wed met three months earlier when a Greek friend took me to lunch at Somers restaurantEfendy, in the Sydney suburb of Balmain. The meal we ate shattered my stereotypes about Turkish food, and our conversation demonstrated that Somer was not only a great cook but also a great scholar.

Our Greek friend, Janni Kyritsis, was happy to concede that while Greek cooking had stagnated, Turkish cooking seemed still to be evolving. With a mischievous smile, Somer told us: Turkish is one of the three great cuisines of the world, but only Turks know this. The other two are French and Chinese, but the French got their cream sauces from our yourt , and the Chinese got their dumplings from our mant .

It became apparent that Somer likes to make fun of his countrymens tendency to claim ownership of every great cooking technique in the Western world, and to cling to absurd food myths that promote Turkish nationalism. He prefers to use the more ancient word Anatolia when talking about the geographical area that is now called Turkey, and to give credit to the many cultures that contributed to the regions food repertoire.

I asked Somer if hed be interested in doing a book that would challenge old theories about Turkish cooking and create a few new ones; that would give readers a way to recreate classic dishes at home and also help them understand what theyre eating when they visit Turkey.

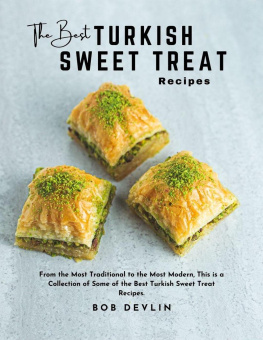

We worked up a pitch to Sue Hines at Murdoch Books, and three months later were flying towards the Garden of Eden. The town of Gaziantep turned out to be very strange. For breakfast, they eat liver kebaps or chilli soup. They make the best baklava in the world, using the best pistachios. They proudly preserve a cooking style that has never needed to make compromises with tourism. Whether or not it was once paradise, it was the best possible place for me to begin my lessons in Anatolian culture.

Gaziantep has a tradition that inspired the way we approached this book. Whenever a family has to spend the day rolling the hundreds of tiny meatballs that go into a festive soup called yuvalama , they bring in a professional storyteller to keep the rollers from getting bored.

We decided to tell a tale with every recipe. Sometimes we would talk about the mythical origins of the dish or its ingredients, sometimes we would talk about Somers first experience of the dish, and sometimes we would talk about its place in the rituals and fashions of ancient and modern Anatolia.

Working with Somer, I learned that Anatolian cooks take a pretty relaxed approach to their creations. They rarely use written recipes and, when they do, the instructions tend to be vague, as in measure with your eyes, add whatever it needs; or else poetic, as in cut into birds heads (cubed), small as a rats tooth (finely chopped) or till the dough has the texture of an earlobe. Weve tried to avoid the vagueness but retain the relaxation. While breads and pastries need precise measures, most other recipes can be varied according to your tastemore chilli, less onion, more vegetables, less meat, as you fancy.

The stories and the recipes are told in Somers voice. I hope you enjoy your conversation with him and share the joy I experienced in learning about an approach to lifes greatest pleasure that is still evolving after 5000 years.

DAVID DALE

The Kadky apartment block where Somer grew up: We had Greek, Armenian and Sephardic Jewish neighbours, and I was blessed to taste their meals.

SOMERS PREFACE

The 1970s was an eventful decade in Turkey, and not only because I was born then. In 1971, the military staged a coup for the second time (the first one being in 1960); left-wing students and right-wing militants supported by the government were at war with each other; and day and night curfews were in place.

I grew up knowing the difference in sound between a gunshot in the next street and a bomb in the next suburb. Even in the midst of civil war, my babaanne (grandma) retained her sense of hospitality. Do not close the door, Somerour neighbours might think we want to keep them away, she would tell me every time I shut the door to the family apartment in Istanbul.