PRAISE FOR REBECCA SEAL

ISTANBUL: RECIPES FROM THE HEART OF TURKEY

The food of Istanbul is as rich, colourful and multilayered as the ancient culture that created it. Rebecca Seal successfully manages the unimaginable: bringing it to us in its full magnificent glory.

YOTAM OTTOLENGHI

Rebecca Seal has captured the vibrant cuisine of a stunning destination, where East meets West.

COND NAST TRAVELLER

Gently spiced recipes evoke the souks of Europes coolest city.

RED

[A] photogenic food tour of Turkeys seductive second city.

FOOD & TRAVEL

Rebecca Seals love letter to Turkeys largest and most fascinating city is beautifully designed with vibrant photography.

METRO

Showing us how to bring the best of Turkish cooking home with us

TOP SANT

THE ISLANDS OF GREECE: RECIPES FROM ACROSS THE SEAS

Seductive recipes that touch the senses, the curiosity and the wanderlust.

FOOD & TRAVEL

Plates that taste of sunny holidays.

RED

To our daughter, Isla Mae Joyce

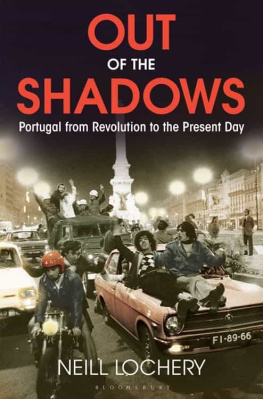

L isbon sits at the mouth of the river Tagus, ranged across seven hills. White, peach and yellow buildings cover the steep slopes, their terracotta roofs rising and falling across the skyline, the peaks dotted with brilliant white domes and towers. This is one of the oldest cities in Europe and its pale cobbled pavements have been worn slippery and smooth by centuries of feet. Because of its important maritime location at the far south west of mainland Europe, Lisbon has been brutally fought over in its long history, ruled by Greeks, Carthaginians, Romans and North African Moors before finally being over-run by Christian invaders, who took and kept the city in the 12th century.

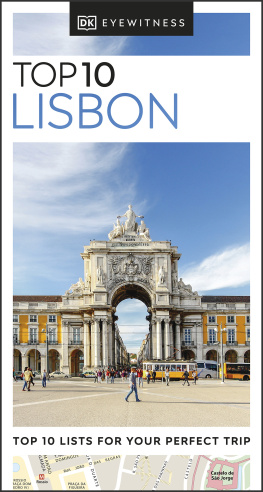

Within a few generations, ships were leaving Lisbon to at first discover, then subdue, much of the rest of the known and unknown world. For nearly six centuries, the Portuguese empire stretched through Asia, Africa and South America; its trade routes spread still further, making Lisbons merchants rich through the sale of spices, alcohol and silk, as well as slaves. By the 16th century, Lisbon was one of the wealthiest cities in the world. Despite being partially destroyed by a huge earthquake in 1755, much of Lisbons opulent architecture from this extravagant era, and from the Moorish years before it, survives today, the citys famous cathedrals, tiled houses, monasteries and castle attract tourists, rather than rampaging invaders. Years of political and economic turmoil have left todays Lisbon with a timeworn air, and both the plain, modern concrete apartment blocks on the edges of the city and its ancient centre are peppered with graffiti and pocked with empty, abandoned and overgrown lots.

Lisbons past has influenced far more than just its architecture. The Moorish and then the colonial periods changed the countrys food completely the Moors brought figs, almonds and coffee, while later, hot chilli peppers arrived on explorers ships returning from South America. Cinnamon came from Sri Lanka and sweet oranges from India. Even salt cod, which comes from cold, north Atlantic waters, not those surrounding Portugal, owes its popularity to the countrys maritime history. The Portuguese were involved in the early international trade in cod, and salted fish travelled well, making it an ideal ingredient for ships cooks. The Portuguese are the highest consumers of fresh fish and seafood in Europe, and fourth in the world. Even tiny supermarkets have wet fish counters, as well as shelves stacked with huge slabs of salt cod; in the big food markets, mostly female fishmongers deftly gut and fillet monkfish, mackerel, long black scabbardfish, eels, hake and swordfish, and sell net bags bursting with cockles, clams and crabs.

Much more recently, an increase in the number of migrants from former African colonies changed Lisbons food again as people from Cape Verde, Mozambique and Angola found new homes in the city, alongside Brazilians and Goans, bringing bright red palm oil and tapioca, and meat stews like chicken muamba from Angola, and chacupa from Cape Verde. All this, combined with Portugals own fertile farmland, plus produce from the Atlantic Azores islands and Madeira, means that the markets in Lisbon are packed with wonderful vegetables, fruit, fish and meat.

Food matters here. Until recently, a working weekday lunch break was always an hour and a half, and would usually include a glass or two of wine. Even now, as life becomes more rushed, the majority of workers eat lunch in a restaurant, even if it is a simple one. Mealtimes are important. As chef Kiko Martins put it to me, When we are eating lunch, we are talking about dinner. When we are eating dinner we are talking about what to eat tomorrow. The conviviality of a shared meal is central to Portuguese life, which explains the petiscos tradition. Like a heartier version of Spanish tapas or Middle Eastern mezze, petiscos are served to share; unlike their smaller cousins, petiscos can be really filling and may look more like a main course than a small plate.

While researching this book, I found that the cooks and chefs I met in Lisbon all shared a deep commitment to preserving the citys foodways. Their knowledge was heartfelt and detailed they knew just how long their favourite salt cod had been cured, how to check the guts of a fish or the stem of a cauliflower to assess its freshness, or where to buy the best tinned sardines. (Thats not to say Lisbon is immune to outside influences every chef I spoke with worried about whether cooking skills are being lost among young people, or whether the arrival of new foods, like gourmet burgers, will edge out older Portuguese dishes.) Because Lisbon attracts people from all over the country (as well as from all over the Portuguese speaking world) you can eat specialities from every region here, which is how I justified to myself including things like a northern soup, caldo verde, or pork from Alentejo, in a book ostensibly about Lisbon.

Inevitably, a single book cannot represent the whole of Portuguese gastronomy these recipes are merely my favourites, the ones I feel are most important; those which resonate the deepest with me and between me and the people whom I met and learned from in Lisbon.

A few key flavours do run through all the recipes, though. Refogado forms the base of many savoury dishes, much like an Italian sofrito or French mirepoix. Refogado means to saut onion in fat, often olive oil, until translucent, but it always comes with at least one and usually several of the following: garlic, bay leaves, paprika, parsley or coriander. Together, these aromatics make up the core flavours in Portuguese savoury cooking indeed, even the smell of