IMAGES

of America

SEATTLES

WATERFRONT

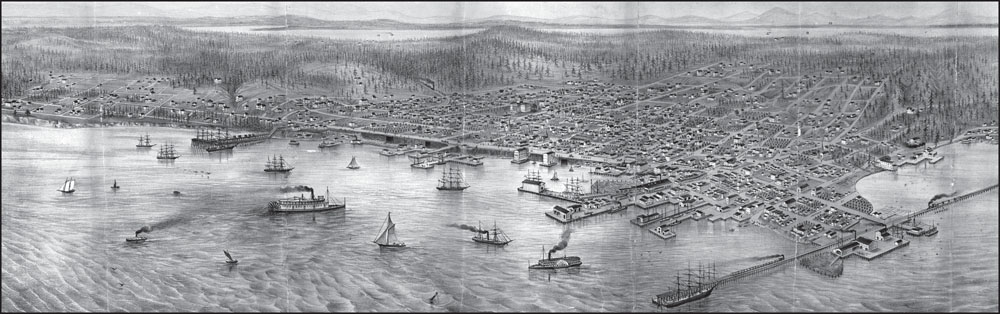

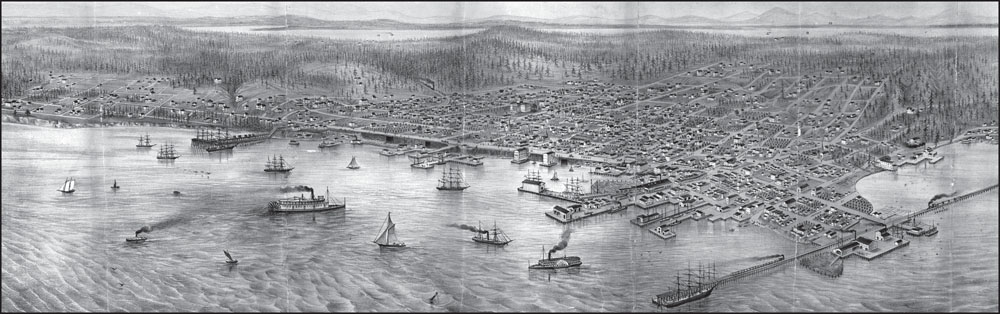

BIRDS-EYE VIEW OF THE WATERFRONT, 1904. Seattles central waterfront, Pioneer Square, and the area now known as SoDoor South of the Dome (i.e. Kingdome, opened in 1976 and demolished in 2000), which was originally a marshy estuarine tidelandare illustrated in this 1904 image. The image also shows two railroads that delivered coal and timber to Seattles waterfront (the Seattle & Walla Walla Railroad and the Seattle Coal and Transportation Company Railway), as well as the Oregon Improvement Company coal bunkers that were critical to the energy supply line for ships. Seattles original banks are visible to the north, while the southern shoreline had already been altered since its initial settlement in 1852. (Courtesy Washington State Historical Society.)

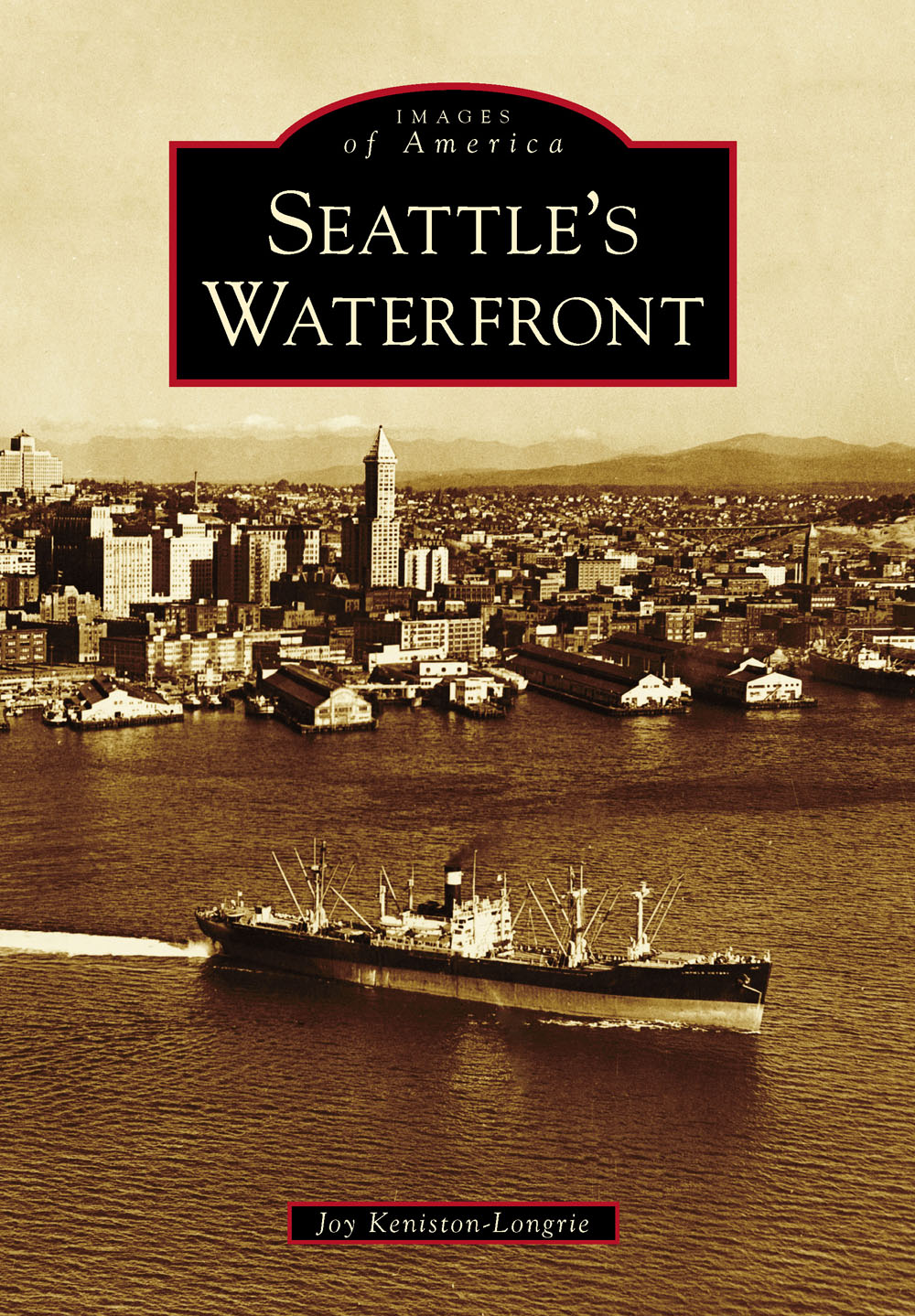

ON THE COVER: Smith Tower, once the tallest building west of the Mississippi, rises above Seattles waterfront in this c. 1940 photograph, which was taken sometime before construction began on the Alaskan Way Viaduct in 1949. The piers along the shoreline were essential for loading and unloading vessels and served as economic mainstays for decades. (Courtesy Seattle Public Library, shp-20047.)

IMAGES

of America

SEATTLES

WATERFRONT

Joy Keniston-Longrie

Copyright 2014 by Joy Keniston-Longrie

ISBN 978-1-4671-3052-3

Ebook ISBN 9781439648742

Published by Arcadia Publishing

Charleston, South Carolina

Library of Congress Control Number: 2013944843

For all general information, please contact Arcadia Publishing:

Telephone 843-853-2070

Fax 843-853-0044

E-mail

For customer service and orders:

Toll-Free 1-888-313-2665

Visit us on the Internet at www.arcadiapublishing.com

Dedicated to past, present, and future people who interact with Seattles waterfront

CONTENTS

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Special thanks go to: Daniel Anker, Mary Azbach, Sally Bagshaw, Rick Chandler, Rick Conte, Bob Donegan, Doris Keniston Driscoll, Jodee Fenton, Ann Ferguson, Leonard Forsman, Hanna Fransman, Leonard Garfield, Sandra Gurkeweitz, Edith Hadler, Paula Hammond, Cecile Hansen, Julie Irick, John Lamonte, Dennis Lewarch, Carolyn Marr, Brandon Martin, Jennifer Ott, Randi Purser, Chad Schuster, Lydia Sigo, Vicki Sironen, Jared Smith, Janet Smoak, Peter Steinbreck, Erin Tam, Diana Turner, and Tracy Wolfe.

The following organizations provided images for this book and have been abbreviated throughout as:

Alaskan Way Viaduct (AWV)

Bainbridge Island Historical Society (BIHS)

Duwamish Indian Tribe Museum (DIT)

International Longshore and Warehouse Union (ILWU)

Museum of History and Industry, Seattle (MOHAI)

National Marine Fisheries Service (NMFS)

National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) Puget Sound Marine Historical Society (PSMHS)

Seattle Municipal Archives (SMA)

Seattle Public Library (SPL)

Seattle Tunnel Partners (STP)

Suquamish Indian Tribe Museum (SIT)

Tacoma Public Library (TPL)

Talkeetna Historical Society (THS)

US Fish and Wildlife Service (USFWS)

US Geological Survey (USGS)

US Library of Congress (USLOC)

University of Washington Special Collections (UWSC)

Washington State Archives (WSA)

Washington State Department of Transportation (WSDOT)

Washington State Historical Society (WSHS)

Washington State University Manuscripts, Archives, and Special Collections (WSU-MASC)

INTRODUCTION

Located on the shores of Elliott Bay on Puget Sound, Seattles waterfront has played an important role in history. Puget Sound was known as the Whulge by the Coast Salish tribes that occupied its shorelines. Puget Sound has also been referred to as the Salish Sea. Seattle has many miles of marine, estuarine, and freshwater waterfronts. This book primarily focuses on Seattles central waterfront and the area south of Pioneer Square, now known as SoDo due to significant changes along the shoreline of what was once a marshy estuarine area. Seattles waterfront represents different things for different people with unique perspectives. Some values are similar and supportive of one another, while others may be mutually exclusive. This introduction presents five different perspectivesfrom the Suquamish and Duwamish tribes, the transportation and business sectors, and an elected officialon the importance of Seattles waterfront.

SUQUAMISH TRIBE

The Seattle waterfront is a place of great cultural, economic, and spiritual importance to the Suquamish Tribe. Chief Seattles father lived across the sound from Seattle at Suquamish, where he raised his son to adulthood. Before contact with Europeans, the shore of Elliott Bay was home to winter villages and other places of ancient tribal use. The people who lived here had strong family connections to the Suquamish, who depended on the salt water for their livelihood, while the upriver groups relied on the Black, White, Green, and Duwamish Rivers to serve as intermediaries to both groups.

Between first contact in 1792 and the first settlers at Alki Point in 1851, Seattle grew and eventually attained his chieftainship. Chief Seattle was now a noted speaker with great influence over neighboring tribes and strong political and economic contacts among government officials and Seattles first businesspeople. He used his influence to keep many of the Puget Sound tribes from joining the Indian Wars that had erupted after the conclusion of treaty negotiations in 1855, essentially saving Seattle from destruction. It was during this time that Chief Seattle gave his famous speech on the Seattle waterfront. Chief Seattle and his people, many from Elliott Bay, retired to the Port Madison Indian Reservation at his ancestral home of Old Man House after signing the 1855 Treaty of Point Elliott.

The city that bears Chief Seattles name in honor of his many actions that helped the town attain success continued to be a part of the Suquamish economy just as it had for thousands of years. Suquamish fishermen provided fish and clams for Seattle markets, initially shipping by canoe and later by Mosquito Fleet ferries that stopped daily in Suquamish. The cultural bond between the Suquamish Tribe and the City of Seattle continues primarily through shared reverence for Chief Seattles gravesite at the Suquamish Tribal Cemetery, marked by Mayor Ed Murrays visit to the grave on his 100th day in office in 2014 and Mayor Greg Nickelss support of gravesite restoration in 2009. The Suquamish people still fish for salmon in Elliott Bay and participate in cultural events in the city, such as the annual Salmon Homecoming on the waterfront.

Leonard Forsman

Leonard Forsman has served as Tribal Chairman of the Suquamish Tribe since 2005. His passions include tribal education, cultural preservation, gaming policy, and habitat protection. He has served on the Tribal Council for 24 years, worked as an archeologist for Larson Anthropological/Archaeological Services, and is the former director of the Suquamish Museum. Forsman is a graduate of the University of Washington. In 2013, Pres. Barack Obama appointed Forsman to the Advisory Council on Historic Preservation.

DUWAMISH TRIBE

A long, long time ago, before settlers arrived to invade this unique waterway, the waterfront of what is now Seattle was undisturbed, pristine. The natives, the Duwamishwhich means people of the insidelived here. The Duwamish went about their routine survival way of life, passing through by their mode of travel in the native canoe. They would go into the surrounding forest, select a certain cedar tree, slide it to the waterfront, and begin carving a canoe. The natives would fish the waters, gathering seafood such as clams, which were plentiful at that time. The natives would build their housestransitory dwellings, as they lived along the lakes and rivers, where they would pick wild berries and roots. They would cut down cedar trees that grew in the surrounding woods to create shingles for the roofs of their homes. The cedar trees provided materials to make baskets for food, cooking, and storage, as well as clothing and hats.

Next page