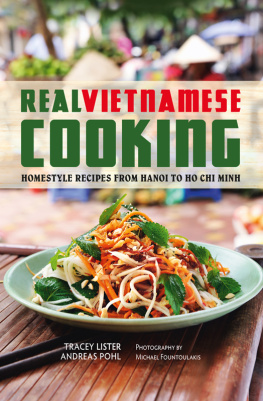

For our daughter, Franka

A SHORT INTRODUCTION TO VIETNAMESE CUISINE

Tracey and I are often asked to describe Vietnamese food and it is a question we always find difficult to answer. How is it even possible to define a national cuisine with the breadth and depth of Vietnamese food? A cuisine that encompasses food from both the mountains close to the Chinese and Lao borders and from a 3400 kilometre-long coastline. A cuisine that is marked by both the four seasons of the Red River Delta in the north and the tropical wet and dry seasons of the Mekong Delta in the south. A cuisine that has assimilated an array of culinary influences ranging from French and Chinese cooking to Khmer and Cham food traditions.

We feel that the most fitting phrase to describe the common characteristics within all that diversity is understated elegance, because as a national cuisine, Vietnamese dishes combine simplicity with sophistication and display a light touch even in the more rustic dishes. It is a food culture that has been shaped by a subtropical climate, a long history of wet rice cultivation and the ability to readily absorb foreign influences.

Rice, fish and herbs are the cornerstones of Vietnamese cuisine. Wet rice cultivation requires a lot of terrain and there is very little tradition of animal husbandry given the scarcity of land not earmarked for growing the nations staple. Meat is used sparingly, mainly for an additional layer of taste and texture and, in the past, it was mainly reserved for guests, pregnant women, children and the ill.

Only since the French colonised the country and the Vietnam War has there been more emphasis on eating meat. Western eating habits have been responsible for new, phonetic word creations in the Vietnamese language such as bit tet for beef steak or xuc xich for sausage, illustrating how the consumption of beef and pork has assumed greater importance.

In a country dotted with ponds and paddies, crisscrossed by rivers and canals and bordered on the east by a 3400 kilometre long coastline, however, it is no surprise that fish and crustaceans are the main source of protein. And that includes the ever-present fish sauce, nuoc mam: the slightly pungent mainstay of Vietnamese cuisine and an ingredient in virtually every recipe.

Yet what really sets Vietnamese cuisine apart from the food of other countries in the region is its judicious use of aromatics. Visit any market and you will find stalls laden with bunches of fresh herbs in vibrant shades of green. It is herbs such as coriander (cilantro), fragrant knotweed and mint that give Vietnamese dishes that certain finesse, often arising from the surprising interplay between strong tastes such as nuoc mam and the delicate flavours and aromas of these leaves.

VIETNAMESE DISHES COMBINE SIMPLICITY WITH

SOPHISTICATION AND DISPLAY A LIGHT TOUCH,

EVEN WITH THE MORE RUSTIC DISHES

Acculturation is the final building block of the countrys cuisine, with the locals adopting foreign influences and twisting them to meet their tastes. Even Vietnams most famous dish, pho, is a product of acculturation, marrying Chinese and French influences to create something uniquely Vietnamese.

The Chinese occupied the country for more than 1000 years and had a strong influence on Vietnamese cooking, but their influence also serves as a good example of how very selective the Vietnamese are in what they choose to adopt. While happy to embrace new cooking techniques and utensils such as the steamer and the wok, the Vietnamese stopped short of taking on board other culinary customs.

Traditionally, Chinese food is characterised by its intricate, complicated cooking methods and rare and expensive ingredients, from which it derives much of its prestige. The Vietnamese, in contrast, insist that they have retained a peoples cuisine based on the delicate combination of simple and accessible ingredients. Interestingly, notwithstanding Vietnams rapid economic growth, peasant food, such as Cabbage with Nuoc Mam and Boiled Duck Eggs, is starting to appear on the menus of fashionable city restaurants. Maybe rich people are looking for a more authentic experience nowadays, muses Hanoi veteran publicist Huu Ngoc about this recent phenomenon which sits well with the nostalgic idealisation of the countryside and village life in Vietnam.

While the Vietnamese rejected the Chinese traditions of manipulating exotic ingredients, they readily integrated Chinese spiritual traditions into their food philosophy: the impact of Taoism and particularly Confucianism can be clearly seen in Vietnamese cooking.

One key concept of Taoism is the notion of complementary opposites, best illustrated in the famous Yin and Yang emblem. This idea extends to eating, with food being categorised as either cold or hot. In keeping with the Taoist philosophy of uniting opposites, a healthy diet should include both. Pineapple, for example, is considered cold and is therefore served with a hot chilli and salt dip. For the same reasons, cold snails are often paired with hot ginger.

The influence of Confucianism is even more pronounced and the figure of 5 plays a central role. In Confucian philosophy the natural world is made up of five elements wood, fire, earth, metal and water and everything follows on from there. A balanced meal should contain five nutrients (carbohydrates, fat, protein, minerals and water) and should appeal to all five senses, including sound, smell and sight. This might explain the fact that eating noisily is not necessarily frowned upon and that the fashion of intricate vegetable carving discarded in the West is popular in Vietnam.

Most importantly, however, a complete meal must include all five tastes sour, bitter, sweet, spicy and salty. Hence the great importance of the dipping sauces which make up any tastes missing from the main dishes. For only with the harmony of all five flavours can one achieve the perfection of a Vietnamese meal.

REAL VIETNAMESE COOKING IS ABOUT THE DISHES WE LOVE AND THE RECIPES WE HAVE COLLECTED OVER THE MANY YEARS WE HAVE BEEN LIVING AND TRAVELLING IN THIS DIVERSE AND VIBRANT COUNTRY

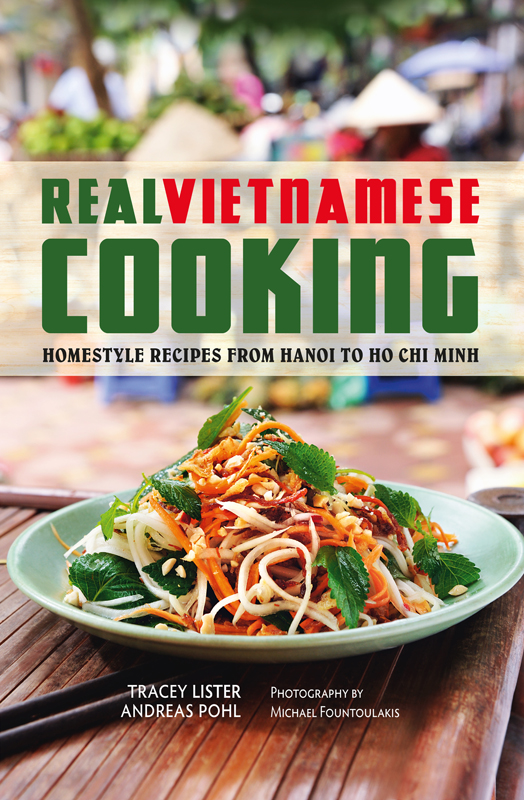

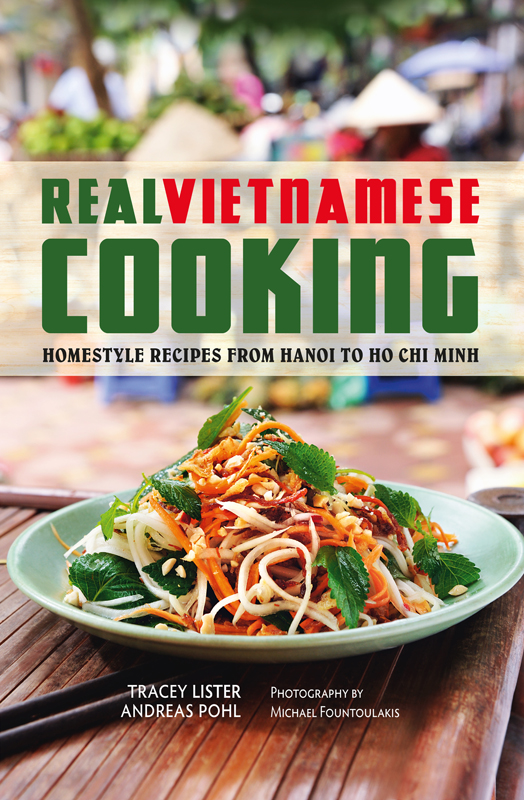

It is about the memorable meals we have had at street stalls, countryside eateries, bia hois and family gatherings which piqued our culinary interests. It also covers the three main culinary regions of the country: the hearty food of the cooler North, dishes from the Centre with its tradition of the imperial cuisine from Hue, and the sweeter and spicier food from the tropical South. The recipes range from classic Vietnamese fare such as Beef Noodle Soup (Pho Bo), Spring Rolls (Nem) and Banana Flower Salad as well as lesser known recipes like Eel in Caul Fat and Boiled Jackfruit Seeds.

While we have retained the traditional chapter headings such as Pork, Beef and Goat, and Fish and Crustaceans, they are more of a guide rather than a definitive description. The recipes are grouped according to their dominant ingredient. In this way, Prawn and Pork Broth with Rice Noodles (Hu Tieu) is listed under Fish and Crustaceans, because the broth is flavoured with dried squid. My Quang Noodles with Prawn and Pork, in contrast, can be found in the Pork, Beef and Goat chapter, because of its straightforward pork broth.

Next page