Introduction

It is something of a paradox in the 21st century that so many of the products made in the village workshops of the 18th and 19th centuries throughout Europe and in the early settlements of colonial America, for a population more interested in function than in fashion, are much sought after on account of their bold simplicity and traditional craftsmanship. We may be thankful for the products and amenities of modern technology but we also enjoy the often more satisfying and visually pleasing products of a bygone age.

Why is this? we may well ask. Is it because these early makers have come to epitomize a time, and a way of life, when the pace was much slower and less stressful than it is today, or is it because of a growing dissatisfaction with the monotony of urban living and the sameness of mass production? The idea of the simple country life certainly appeals to many peoplea trait that television, magazine publishers, and the advertising business fully exploit with their portrayal of village life, farmhouse interiors, and country living. As a consequence, this obvious step back in time and consciousness has brought about a reverence for and a revival of the handmade products of our rural past.

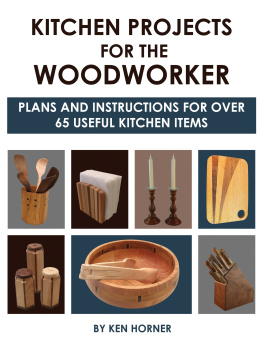

And nowhere is this more apparent than in the increased interest in handmade wooden objects, be they items of furniture, for use indoors and out, kitchen utensils, or containers, racks, and shelves for storage or display. Traditional woodwork, perhaps more than anything else, is central to the so-called country style.

From ancient times, wood has been one of the most used of all our natural resources, and throughout history new ways of using it have continually been found. In the beginning, trees provided mans basic needsfood, fuel, and shelter. Later, evermore sophisticated forms of shelter were devised, and buildings (small and grand), and furniture of all kinds to be used in them, were built of wood, as were boats and ships of all sizes, fences and fortifications, agricultural implements, domestic ware, and household utensils. The earliest airplanes were made from wood, vintage cars have wooden frames, and giant locomotives on their iron road were supported on wooden ties or sleepers. The paper we write on, the pencil we write with, and even the eraser used to correct mistakes began as a tree. The fuels that drive our cars and run our domestic heating come from prehistoric forests that grew and perished long before man appeared on Earth.

The early workers in wood had only the simplest tools, and this is reflected in the simplicity and severely functional nature of what they produced. It is this naivety that appeals to our senses today. The clear step-by-step projects provided in this book, which are organized and color-coded by an increasing level of ability required for the task, should enable and inspire readers to make their own hand-crafted traditional wooden furniture and artifacts that will help capture the essence of country living and style. Living with wood is undeniably pleasurable, and working with it can be deeply satisfying and rewarding.

All measurements are given in inches, with the equivalents in millimeters indicated in brackets.

Scoops & Ladles

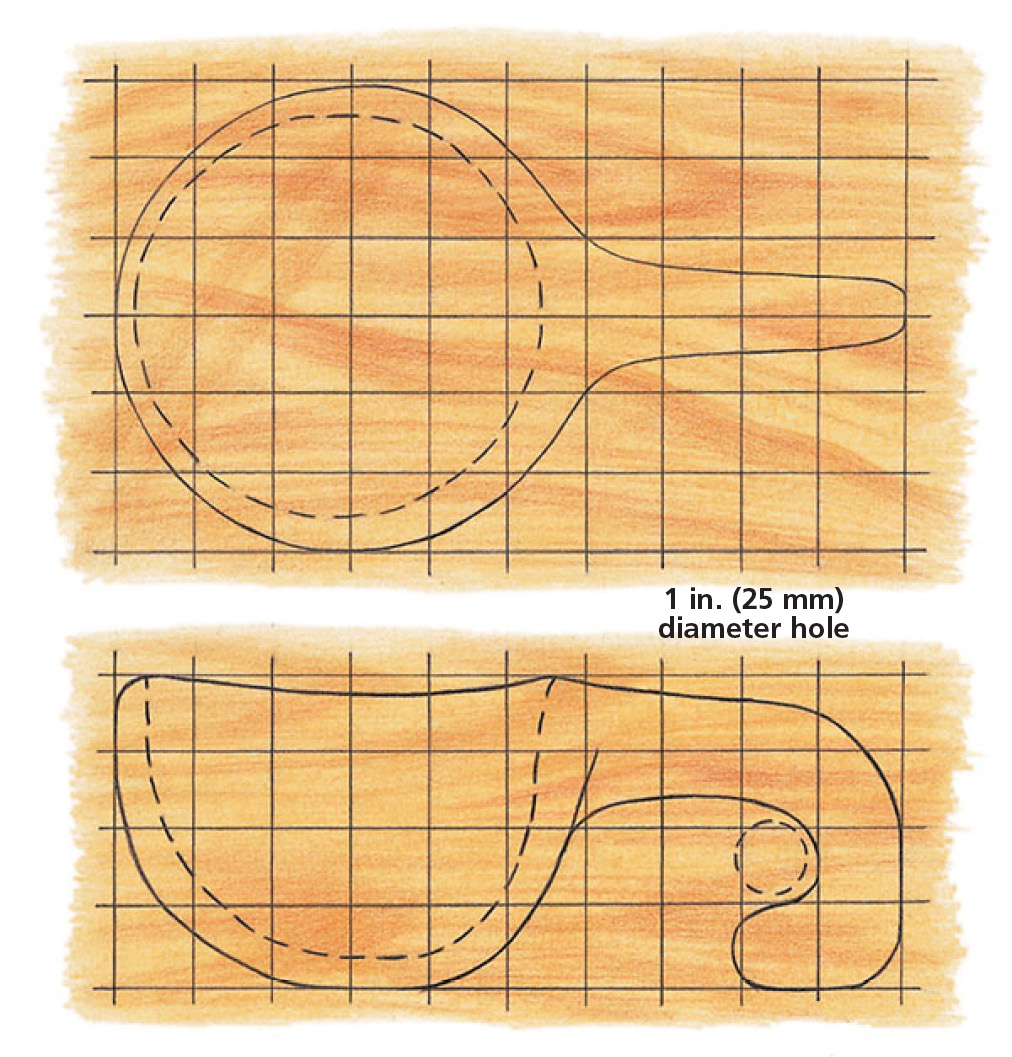

Before plastics and stainless steel, wooden scoops and ladles played an important part in the preparation and serving of food and drink. The words are often used synonymously, but scoops are generally broader and flatter, have short handles, and are used for dry goods such as flour, seeds, and herbs, while ladles usually have long handles and are mainly for use with liquids. Spouts, as on jugs, help direct the flow of the liquid more accurately, and hooked handles allow ladles to be hung up or hung over the side of a container. The short, large, hooked handle on a churn ladle forms a steady support when placed down on a flat surface. Although usually plain, some were decoratively carved.

ABILITY LEVEL

Novice/Intermediate

SIZE

12 x 6 x 3 in. (305 x 152 x 76 mm)

MATERIALS

Sycamore, Beech, Lime

CUTTING LIST

Flour scoop

10 x 5 x 2.5 in. (254 x 127 x 64 mm)

Churn ladle

10 x 6 x 4 in. (254 x 152 x 101 mm)

Ladle with spout

13 x 5 x 3 in. (330 x 127 x 76 mm)

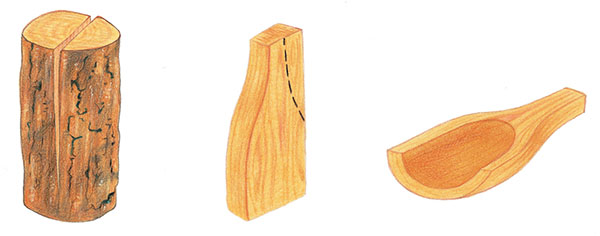

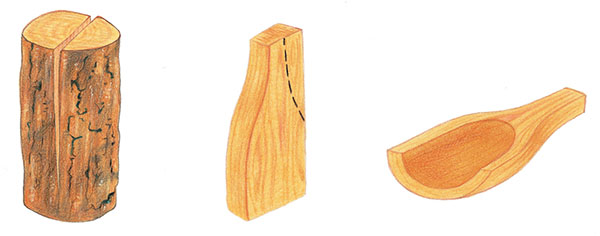

1: Working in the traditional way, a small, often unseasoned log would be selected. This would be split in two and a scoop or ladle chopped out and shaped from each half using a short-handled, very sharp axe.

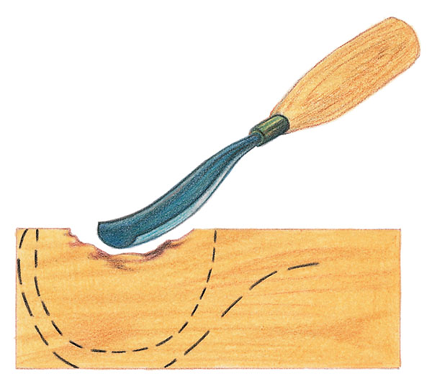

2: The bowls inner shape was then hollowed out using a variety of tools, including curved gouges, hooked knives, orfor larger pieces of wooda small hand adze. The bowl of the scoop or ladle would be completed with a rounded carving gouge or, in some areas (Wales in particular), with a special hooked knife. A curved woodcarvers gouge, of the type known as a long bent gouge, is suitable for this job. The final shaping and finishing of the outside was done with either a short-bladed knife or a drawknife or spokeshave.

3: Early makers were able to use these tools with great skill and little danger to themselves. However, the novice is strongly adviced to employ safer methods of working, at least to begin with.

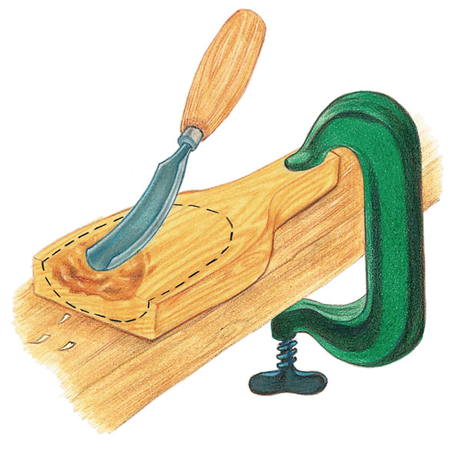

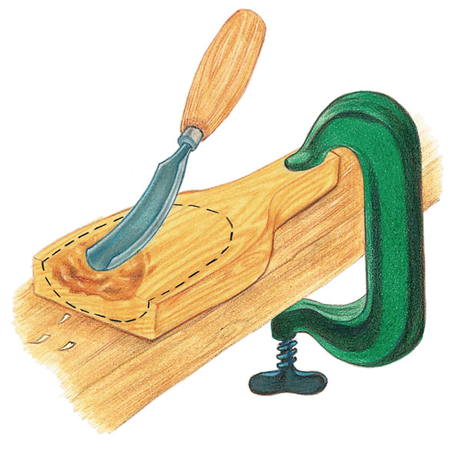

4: More modern methods of working include using sawed pieces of wood, which are marked out in outline and then partially hand- or band-sawed to the required outside shape. The inside shape of the bowl is produced by carving with the workpiece safely clamped to the bench.

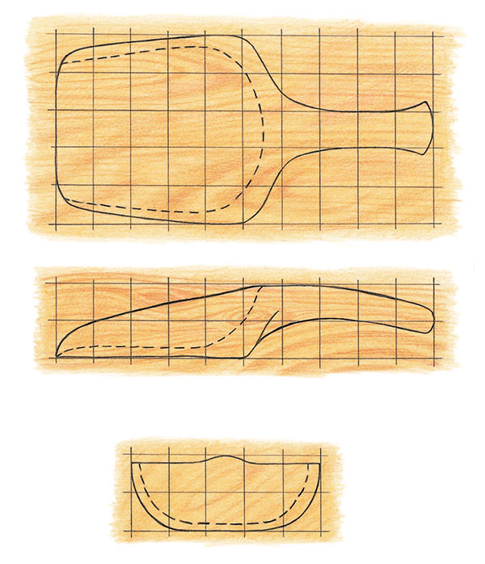

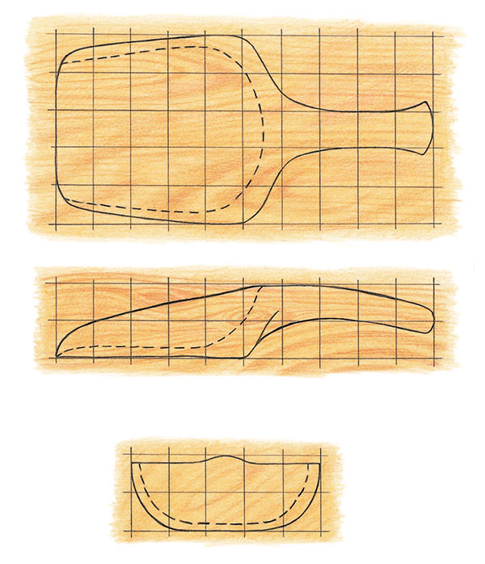

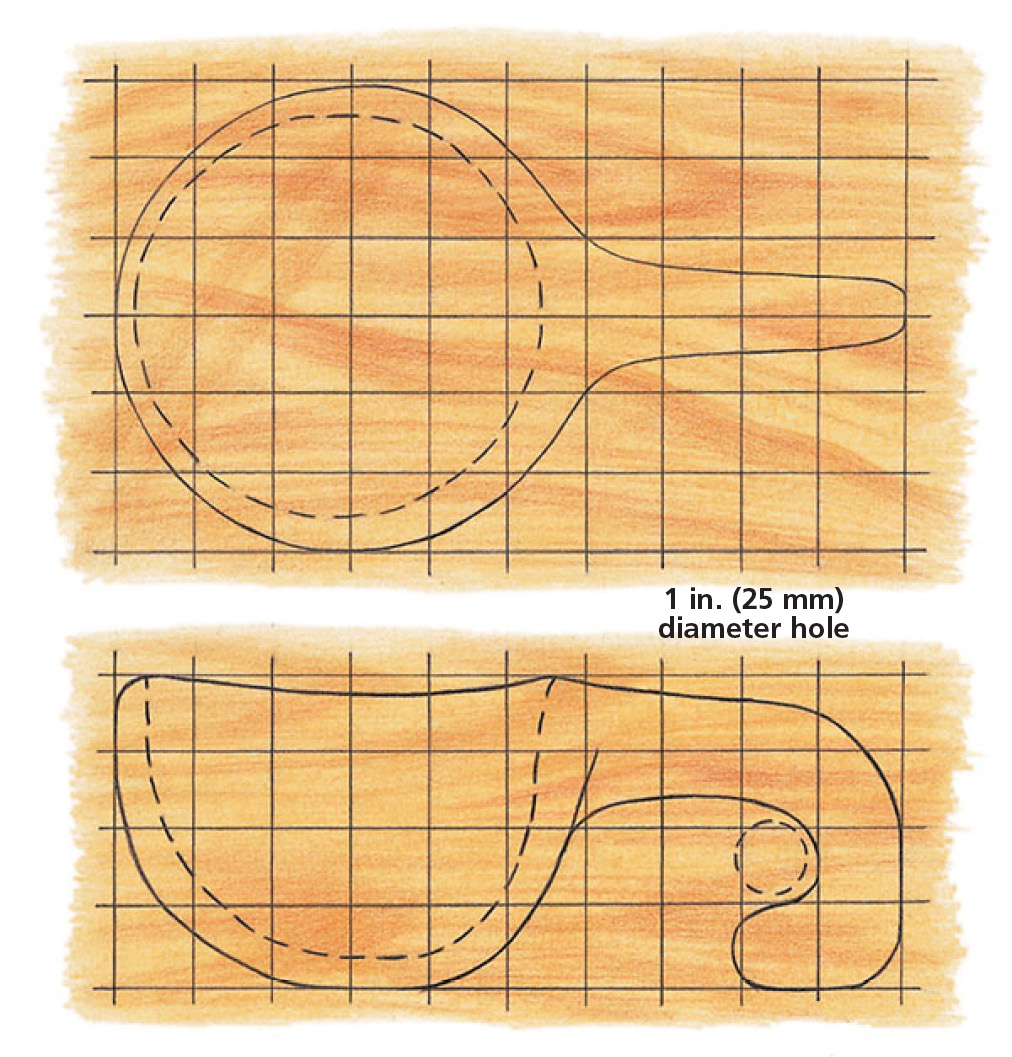

Flour scoop (1 in. / 25 mm squares)

1: To make the flour scoop, mark out the shape on the piece of wood by enlarging and using the pattern produced here. First, mark out and saw only to the plan shape. If you are hand sawing, make sure that the piece is held securely in a vise.

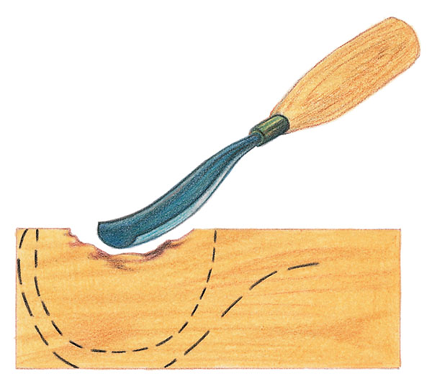

2: With handle portion of the piece clamped, hollow out the concave scoop with a carving gouge. Begin at the front (open) end of the scoop and work gradually backward in stages, biting deeper into the wood each time. Finish off using lighter, longer strokes with the gouge to leave the wood as smooth as you can.

: When you are satisfied with the inside shape and surface, mark in the side view and remove the waste wood down to the lines you have drawn (mainly under the handle). Sawing by hand is best and safest. Complete the outside shape with a spokeshave or use a rasp and file. Next, shape up the handle and bring the front to a firm edge.

4: Finish off the flour scoop by sanding the wood until it is smooth.

Churn ladle (1 in. / 25 mm squares)

1: Because of the generous shape of the churn ladle, you will need a substantial piece of wood. As before, mark out its plan and side views, but do not saw it to shape until after you hollow out the bowl.

2: Clamp the piece to the bench and, using a carvers gouge, begin at the center and work outward, more or less concentrically, to remove waste wood from the bowl. Use the gouge with a scooping action, in conjunction with a mallet if it helps you. Dont let the gouge dig in.

Next page