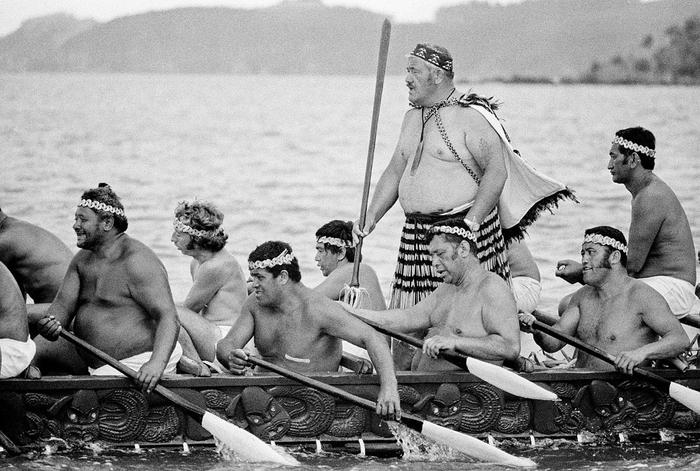

While working on the essays in this book, I received help from many friends and colleagues. In particular, I should like to thank Sir Graham Latimer, Donna Hall, Ted Douglas, Mark Robertshawe and Paul Diamond for commissioning and organising the Waitangi Rua Rau Tau Lecture 2004; Mark Busse of the Association of Social Anthropologists of Aotearoa New Zealand and Lydia Wevers and Louise Grenside of the Stout Research Centre for New Zealand Studies for support in the presentation of conference papers in 2008 and 2009; Dianne Bardsley of the New Zealand Dictionary Centre and John Macalister of the School of Linguistics and Applied Language Studies at Victoria University of Wellington for providing linguistic references; Jocelyn Tarrant of Whanganui for detailed feedback on the draft text of Huarangatia; Jeny Curnow for casting light on the genesis of Allen Curnows sonnet; Jane McRae for advice on the spelling of Maori words; John Miller for photographs that illuminate the events they record; and Auckland University Press, especially Sam Elworthy and Christine OBrien for their enthusiasm for the project, Katrina Duncan and Keely OShannessy for design work and Vani Sripathy for her competence, understanding and patience as editor.

Looking back over more than fifty years of engagement as an anthropologist, I recall with gratitude and affection the many teachers, mentors, informants and friends, both Mori and Pkeh, who have supported, challenged and inspired me in my search for understanding as well as knowledge. Rau rangatira m, he mihi aroha tnei ki a koutou katoa m o koutou manaaki ki aku mahi. Ko koe ki tna, ko au ki tnei kwai o te kete, i tutuki ai te wawata.

The tuamaka of the title of this book is the technical name for a rope plaited in the round from five or six strands of flax fibre, one of the several kinds of rope that the mythical Mori hero Mui and his brothers made in preparation for snaring the sun. The title highlights the frequent use in the book of the Mori metaphor of the taura whiri (the plaited rope), which emphasises the unity and strength that comes from weaving people together.

Complete in themselves, the six essays in this book are related to each other by a shared focus on the central issues of nation-building in Aotearoa New Zealand. They make particular reference to the Treaty of Waitangi, the challenges and rewards of cross-cultural encounter, and recognition of Mori culture as a national resource. Their emphasis is positive and forward-looking: what we can do to turn our difficulties into assets.

Originally written at different times for different audiences, these essays were either revised or completed during 2009. At times they overlap as they deal with the issues from different perspectives, complementing and reinforcing each other, like the strands in a tuamaka. The Mori and English titles of each essay are amplifications rather than translations.

The first two essays both feature the metaphor of the taura whiri, demonstrating its versatility by applying it in different ways. Trangawaewae: The Trick of Standing Upright Here discusses the contemporary relevance of the Treaty of Waitangi and Mori literature in a small compass. He Taura Whiri: The Treaty Our Guide pursues these themes in greater depth. Taking stock of the present state of ethnic relations in Aotearoa New Zealand, it directs our attention to the bicentenary of the Treaty in 2040.

The middle essays, Krero Prkau: Time and the Art of Mori Storytelling and Whakatauk: Wisdom in Proverbs, explore the riches of Mori literature. Both trace the processes and consequences of change, as storytellers adapt their tellings to different audiences and proverbs are applied in multiple settings.

Only recently completed, the final essays explore the related processes of cultural exchange in Aotearoa New Zealand over more than 50 years. Huarangatia: Mori Words in New Zealand English traces the history and current use of 23 words of Mori origin, uncovering significantly different trajectories and balancing losses and gains. Anga Mua: Living History charts the rapprochement between the academic disciplines of anthropology and history as I have experienced it in my own life and work.

Mori is one of New Zealands three official languages, along with English and New Zealand Sign Language. The Mori words in this book are printed without italicisation but retain two markers of their Mori origin: long vowels, which are critical for pronunciation and meaning, are marked with a macron, and plural nouns are given the Mori form, which in most cases is the same as the singular. These words are briefly translated the first time they occur in the text, but, since most have a wide range of meaning, readers are advised to consult the glossary for a fuller understanding.

As an anthropologist I use the terms ethnic group and culture with meanings approved by social scientists and Statistics New Zealand (Metge 1990: 519; Statistics NZ 2008: 10506). The adjective ethnic is derived from the Greek ethnos, meaning a people. An ethnic group is a collectivity of people who regard themselves and are regarded by others as having a common origin (not necessarily involving biological ancestry), culture and history: they are held together by a we feeling. Individuals may identify with more than one ethnic group. I do not restrict the term ethnic group to minority groups but apply it equally to the Pkeh majority. I use culture to refer to the lifeways of particular peoples, summed up as a collection of ways of doing and thinking, a repertoire of possibilities, available to and used by group members in the process of living (Metge 1990: 7). Ethnic group members develop varying degrees of competence in and understanding of their groups culture. In modern complex societies like Aotearoa New Zealand access to more than one ethnic group and culture presents people with choices, which they exercise in different and creative ways.