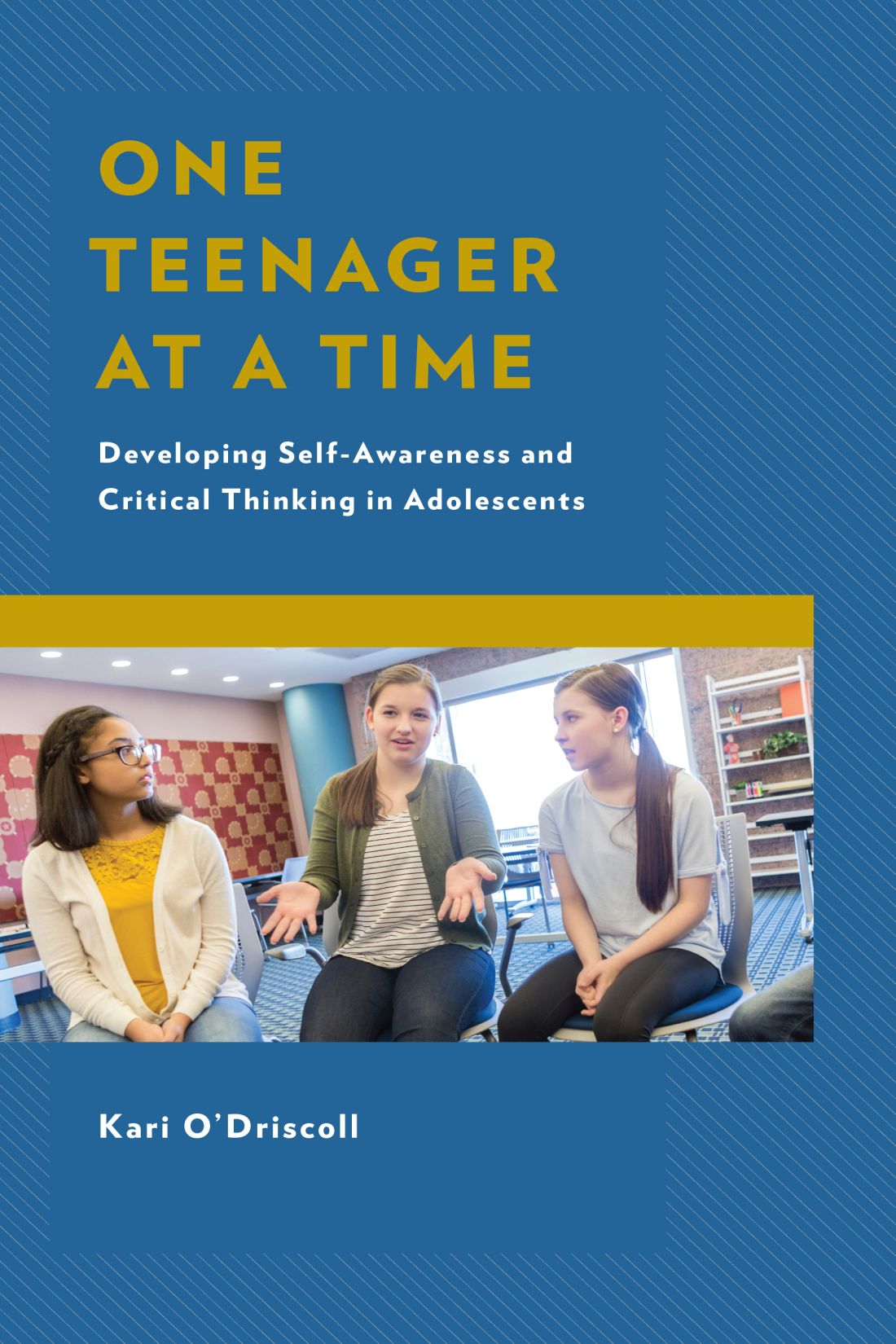

One Teenager at a Time

One Teenager at a Time

Developing Self-Awareness

and Critical Thinking

in Adolescents

Kari ODriscoll

ROWMAN & LITTLEFIELD

Lanham Boulder New York London

Published by Rowman & Littlefield

An imprint of The Rowman & Littlefield Publishing Group, Inc.

4501 Forbes Boulevard, Suite 200, Lanham, Maryland 20706

www.rowman.com

6 Tinworth Street, London SE11 5AL, United Kingdom

Copyright 2019 Kari ODriscoll

All rights reserved . No part of this book may be reproduced in any form or by any electronic or mechanical means, including information storage and retrieval systems, without written permission from the publisher, except by a reviewer who may quote passages in a review.

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Information Available

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Available

ISBN 9781475851458 (cloth : alk. paper)

ISBN 9781475851465 (paper : alk. paper)

ISBN 9781475851472 (electronic)

The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of American National Standard for Information SciencesPermanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI/NISO Z39.48-1992.

The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of American National Standard for Information SciencesPermanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI/NISO Z39.48-1992.

Contents

I began writing this series of discussion prompts and lessons when my daughters were in middle school. I spent years interacting with adolescents, chaperoning field trips, engaging in conversations, and learning about nonviolent communication and mindfulness. My interest in mental health and social development led me to seek out teachings by JoAnn Deak and Dan Siegel. I took classes from Mindful Schools and Bren Brown and The Chopra Center to expand my knowledge.

Research on educational best practices informed the structure of the lessons, and the content was developed over a period of four years. The more I learned about how our brains integrate and process information and the effect our thoughts have on our emotions and overall well-being, the clearer it became that the impact of mindfulness on the developing adolescent brain can be enormous.

Story is an incredibly powerful way to learn, which is why the lessons use story to introduce emotionally challenging concepts. Adolescents are incredibly socially driven; therefore, the group discussion format is a crucial element of this curriculum. Letting students lead discussions and engage in conversation allows them to frame abstract ideas just as their brains are able to appreciate non-concrete concepts.

The activities herein are designed to bring universal concepts to the individual level as well as adding practicality. Bringing the ideas home with guided meditation introduces mindfulness and engages different neural pathways.

These lessons address some of the most pressing issues facing adolescentsfrom ideas about their own worth, to dealing with stress and anxiety, to building community. With the exception of the first few exercises, there is no linear progression required. Educators are encouraged to read the room in their own student groups to determine which lessons will be the most vital on any given day so that they can engage with the students where they are in their own lives.

It will take a skilled facilitator to deliver this content since it offers students a great deal of ownership. They will learn to have difficult conversations without shutting down emotionally, derailing discourse by labeling or name-calling, and become more comfortable collaborating with those whose beliefs and biases are very different from their own. This will enable them to have complex interactions as adults without losing their own identity or feeling threatened.

Educators will need to have a clear eye toward behavior and rhetoric that is hurtful or potentially destructive and enforce strong classroom standards as well as refraining from adding their own ideas and opinions.

The lessons were also designed for maximum flexibility. Every school setting has its own challenges regarding time and resources, so a lesson can be delivered in one sitting or over a period of days during homeroom or advisory periods.

If you choose to break up a lesson into component parts, introduce the lesson during the first period and allow for some discussion. Revisit the discussion the next time you meet and ask if, upon reflection, other thoughts have surfaced. Add the activity during this second meeting. In a third meeting, take some time to debrief with students about discussion and activities and encourage them to share the impact it had on them in their daily lives since you last met. Close with the guided meditation.

No one is an island, especially when youre writing a book. Ive used the work and brilliance of so many others to form my ideas and build upon as I created lessons, worked with students, and wrote meditations. Drs. Dan Siegel and Bren Brown have and continue to make amazing discoveries about the human brain and emotions and the interplay between the two. Dan Gottlieb and Kristin Neff and Christopher Germer have opened my eyes to the power of compassion and empathy, along with Pema Chdrn, Thch Nht Hnh, the Dalai Lama, bell hooks, and Maya Angelou and Gloria Steinem. There are countless others whose work I have devoured and appreciate greatly, but there isnt room here to list them all.

As for the people I know in real life, I first have to thank my daughters, Erin and Lauren, for teaching me what it is to be a mom, for trusting me with their thoughts and feelings and wisdom, and always supporting me on this writing journey of mine. To all their wonderful friendsAlex, SJ, Midori, Maia, Nia, Eleanor, Thomas, Sam, Mosesthanks for the amazing conversations and letting me bounce ideas off of you. I adore you all. Thereza, Jen L., Becky, Tracy, Jodie, Kathy, and Susanyour friendship and love and support buoy me when I need it most. Knowing youve got my back is immeasurably important.

Thanks so much to the amazing mentors Ive had over the years who taught me that passion is one of the most important elements of any successful endeavor. Without that foundational belief, I might have given up on this project a long time ago.

To my fellow writers who have read bits and pieces of this and given me feedback to make it better, I am incredibly grateful. Tonya, Julie, and members of the Mindful Schools online community and the SEL for Washington communityyour input has been so vital to this work. And to Bill in Arkansas and Seth and the students at Seattles Recovery School, thank you for giving this curriculum a shot and helping me refine it.

Every classroom has its own rules, and some portion of the first meeting should be spent talking about them with students. Here are two sets of overlapping rules you can copy, borrow, and adapt for your own purposes. The House Rules were adapted from The Rules of Cooperation from LArche Portland, a faith-based organization whose mission involves supporting individuals with intellectual disabilities. To reflect a positive mindset, theyve been altered slightly.

1. Abundance There is enough of what we all need if we cooperate.

2. Equal Rights Your rights as a person are equal to mine, and we all have an equal responsibility to cooperate.

3. Power Is Not a Tool Used Here Displays of physical power (hitting, slamming doors, etc.), threats, and passive-aggressive behavior (withdrawing, staying angry, refusing to talk, etc.) are not part of a cooperative environment. Anything that is designed to shut down conversation is counterproductive to our purposes.

4. No Rescues If the thought of doing something for you makes me angry or resentful, I will not do it. If I think youre capable or simply avoiding it and I am compelled to save you, doing so will not further our work here.

The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of American National Standard for Information SciencesPermanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI/NISO Z39.48-1992.

The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of American National Standard for Information SciencesPermanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI/NISO Z39.48-1992.