Copyright 2016 by Carolyn Phillips

All rights reserved.

Published in the United States by Ten Speed Press, an imprint of the Crown Publishing Group, a division of Penguin Random House LLC, New York, in association with McSweeneys.

www.crownpublishing.com

www.tenspeed.com

www.mcsweeneys.net

Ten Speed Press and the Ten Speed Press colophon are registered trademarks of Penguin Random House LLC.

McSweeneys and colophon are registered trademarks of McSweeneys, an independent publisher.

Portions of this work previously appeared, sometimes in slightly different form, in Lucky Peach and the San Francisco Chronicle, and on The Huffington Post, Food52, and Zester Daily.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Phillips, Carolyn J., author.

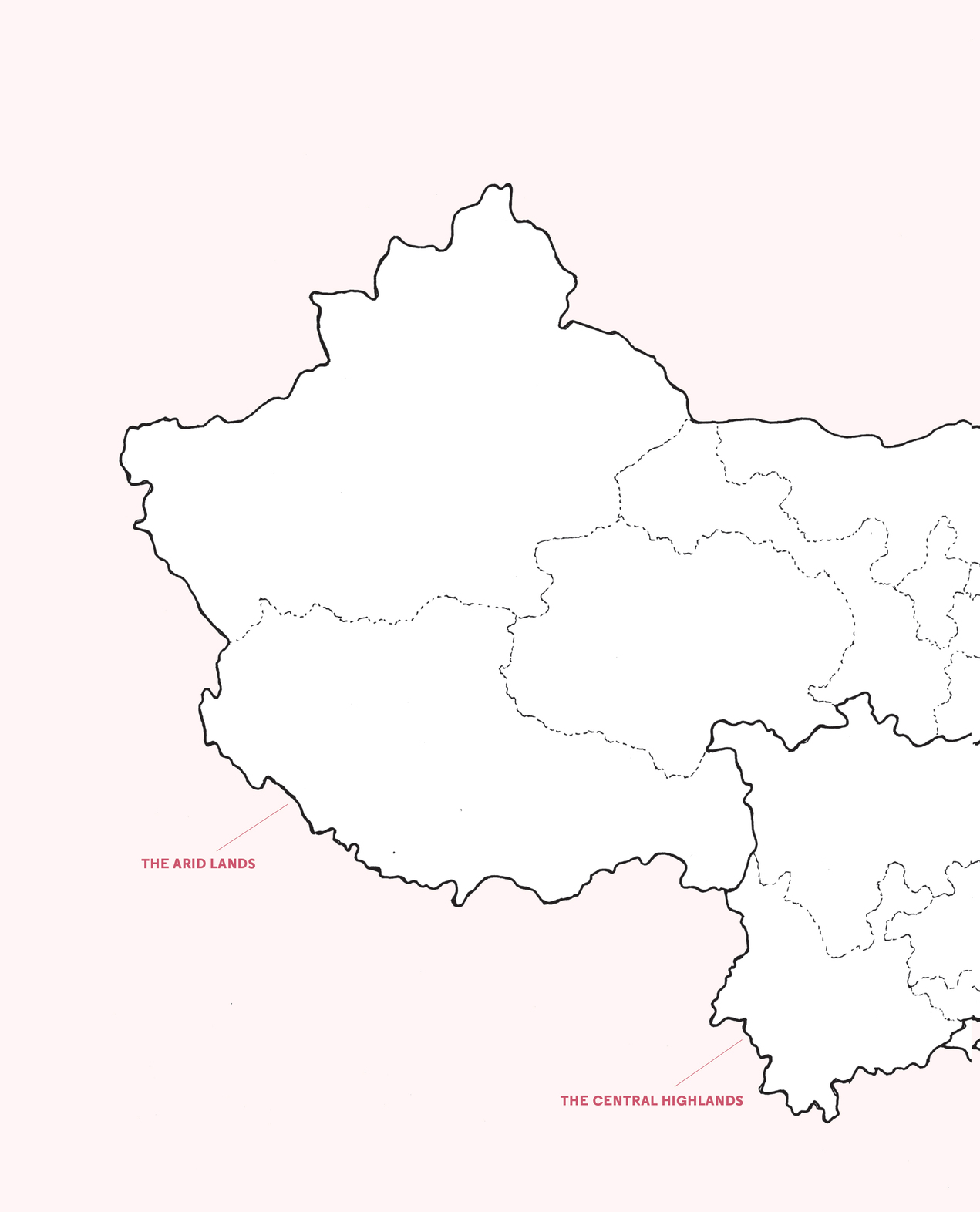

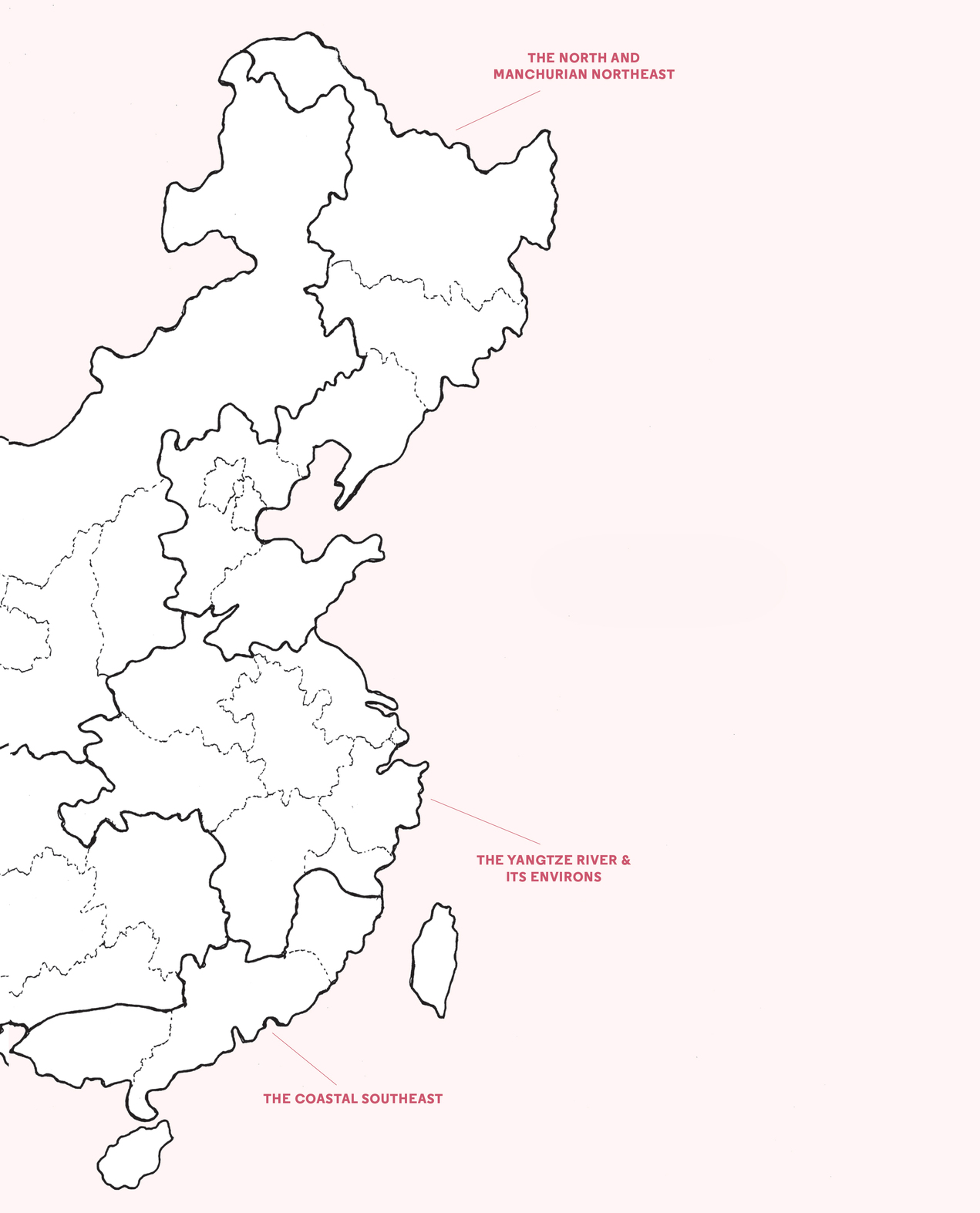

All under heaven : recipes from the 35 cuisines of China / written and illustrated by Carolyn Phillips ; introduction by Ken Hom.First edition.

pages cm

Includes bibliographical references and index.

1. Cooking, Chinese. I. Title.

TX724.5.C5P486 2016

641.5951dc23

2015029244

Hardcover ISBN9781607749820

Ebook ISBN9781607749837

Cover Design by Ashley Lima

v4.1

a

This book is dedicated with humble thanks to the people of Taiwan, Mainland China, and the Chinese diaspora, to their inventive ancestors, and to the endless generations of inspired cooks who together created the best food in the world.

FOREWORD

F ifty-six years ago, when I first worked in my uncle Pauls restaurant in Chicagos Chinatown, I remember that we had two large refrigerators in the kitchen. The first one was for the non-Chinese diners: it was filled with chop suey; the then very popular patties of egg foo yung, ready to be reheated and sauced; and battered pieces of pork for the sweet-and-sour plates. The second refrigerator was filled with fresh scallops and sea conch, dim sum dumplings, birds nests bound for soup, and braised pigeons. The gulf between those fridges could not have been wider. Our non-Chinese diners had only a vague idea of what Chinese food was truly about.

Since then, the Wests idea of Chinese cuisine has changed dramatically. No doubt this transformation has come about for many reasons, the first and foremost being Chinas rise from a poor, underdeveloped country racked by turmoil, revolution, and self-inflicted wounds to one of the leading economic powers in the world. The renaissance of one of Earths oldest civilizations has captured the global imagination. Chinas growth, culturally and economically, has had an enormous impact on all our livesincluding on the way we eat.

For four decades, I have taught Chinese cooking to both interested amateurs and professional chefs, and over the years Ive witnessed how Chinese cookery has evolved outside of China. When I began teaching, in the early 1970s, Chinese food in the United States and in Great Britain was mediocre. Trade embargos restricted the flow of authentic Chinese ingredients and foodstuffs, and many of the Chinese immigrants who came to the West were not actual chefs. The result was cheap fare adapted to the milieus the immigrants lived in. In the States, chop suey, an invented perversion of stir-fried leftovers, became a standard item on Chinese menus; in Britain, Chinese takeaway shops often served curry and chips. As China opened up, though, the quality of Chinese cooking improved immensely. New floods of immigrants brought with them a sense of authentic Chinese cuisine.

Funnily enough, a similar sea change occurred in China itself. I remember how disappointed I was, thirty years ago, by the food I ate in China. It was cooked without passion, care, or love, and served with surly service on top. Good and varied ingredients were hard to come by, and many of the best chefs had already left the country. Fortunately, home cooking still thrived, despite the states attempt at promoting communal kitchens. And in the wake of the economic reforms of the late 1970s, farmers were allowed to grow what they wanted. Within a few years, foreigners began opening restaurants to take advantage of the economic boom, and five-star hotels popped up to meet the demands of travelers from all over the world. Those restaurants and hotels rehired the Chinese chefs who had been lost to Hong Kong and Singapore, and the result was a reemergence of Chinese cuisine. The ever-growing middle class was soon demanding better cooking; enterprising restaurateurs and food companies rose up to respond to their appetites. Chefs and home cooks alike revisited old recipes and started inventing new ones. Today, Chinese food has never been better.

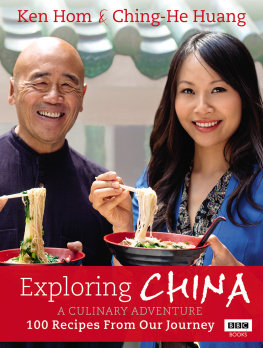

I have always welcomed any book that expands the horizons of our knowledge of Chinese food; now comes one of the best I have seen in ages. All Under Heaven is not just a mere cookbookin fact, it may be the most comprehensive work to date on an incredibly complex subject. Carolyn Phillipss monumental exploration of Chinese cuisine documents classic recipes in exacting detail, but it is also infused with her personal observations and insight, as well as with illuminating bits of historical information. Her meticulous research has helped fill gaps in my own understanding of how certain recipes developed. There are simple, widely known recipes for the novice cook here, such as Guangdong-Style Steamed Fish, but also lesser known and more challenging preparations, such as Beijing-Style Smoked Chicken. I cannot praise Carolyns work enough; I am sure that, in the coming years, All Under Heaven will come to be considered a classic, as well as an invaluable reference for any serious cooks kitchen.

Ken Hom

Widely regarded as one the worlds greatest authorities on Chinese cooking, Ken Hom, OBE, is an award-winning celebrity chef, television host, and best-selling author of thirty-six books that have been published in more than sixteen languages.

AUTHORS NOTE

C hinas cuisines have always proved too tantalizing for me to ignore. When I arrived in Taipei as a young student in the mid-1970s, though, I didnt have an inkling of what was in store for my palatenothing I ate was anything like the so-called Chinese food I had eaten in the States. As I started to roam around the city, fragrant aromas lured me into little restaurants that plied me with specialties from all over China. Taipei was still a quiet place then, but by wandering its labyrinth of alleys and side streets, I discovered not just the home-style dishes and street snacks of the local Taiwanese and Hakka people, but also delicacies imported by Mainlanders from Shandong in the north down to Guangdong in the south, and from Shanghai in the east out into Chinas Muslim west.