Creative Knitting

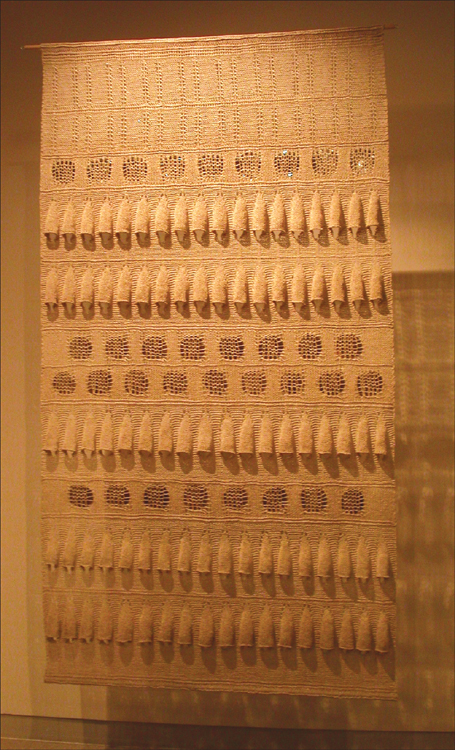

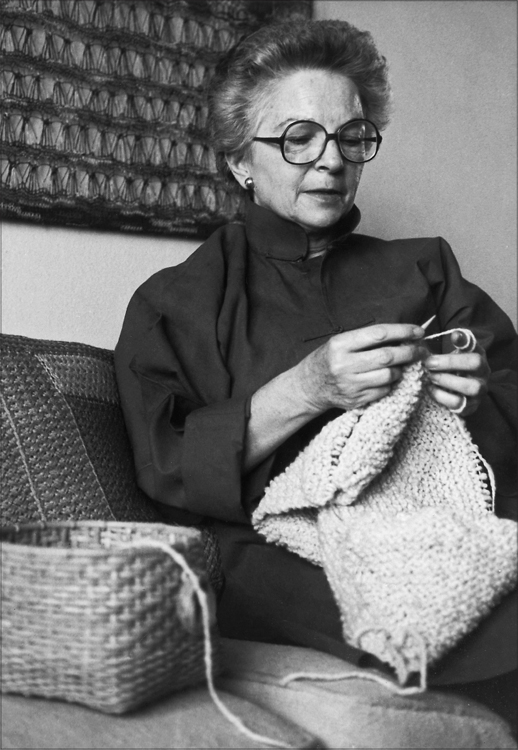

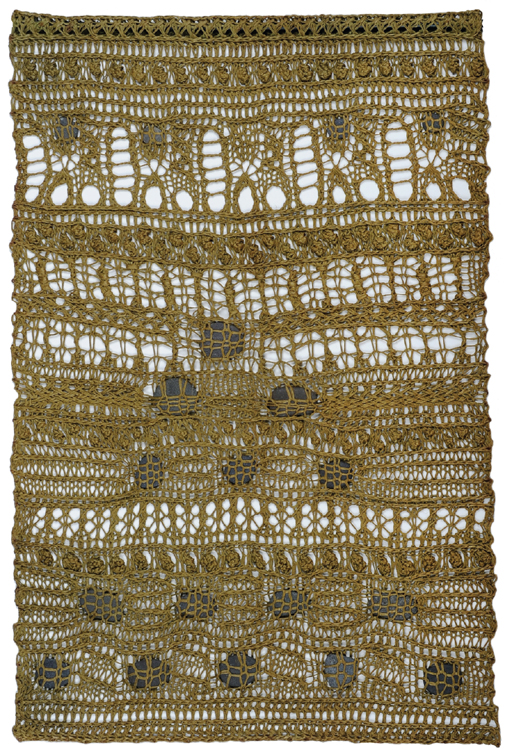

Bell Frilling and Mica, wall hanging, 42 78, (1975). Linen, linen boucl, and mica. (Photograph by the editor.)

Creative Knitting

A NEW ART FORM

NEW & EXPANDED EDITION

Mary Walker Phillips

Edited by

Patricia Abrahamian

Dover Publications, Inc.

Mineola, New York

IMITATION WILL FASHION WHAT IT HAS SEEN, BUT IMAGINATION GOES ON TO WHAT IT HAS NOT SEEN

APOLLONIUS OF TYANA

Dedication

This book is dedicated to my mother, Mrs. John P. Phillips, and also to my sister, Mrs. Glenn A. Stackhouse; to my brother, William David Phillips; and to their respective families.

Authors Acknowledgements

There are many people who have encouraged me and have graciously given their constructive comments. Without their help I am sure this book would never have come into being. To all of my friends, thank you. I am especially grateful to the American Craft Council, Jean Kofoid, Shirley and William Sayles and Milton Sonday. Jack Lenor Larsen, by his remarks concerning knitting, reactivated my knitting needles and is one of the persons most responsible for my in-depth involvement with knitting. To Jack, my special thanks.

Editors Acknowledgements

I am indebted to Mary Walker Phillips for sharing her knitting, her library, and her genius with me. Above all, I treasure her remarkable gift of friendship.

I am grateful to Marys brother W. David Phillips and his family for their many kindnesses and for inviting me to help bring this updated book to knitters once again.

My thanks to textile expert Melissa Leventon and to my dear friends Kathleen Dowell, Alain and Mary Ekmalian, Alice Kezirian, and Constance Swank. Each in a special way helped in the editing of this book.

Dover Editor-in-Chief M.C. Waldrep and Acquisitions Editor John Riess provided critical input and advice regarding the book from beginning to end. New York Times reporter Margalit Fox offered the perfect description of Marys work when she wrote, Miss Phillips knit jazz. I cannot thank them enough.

Words are simply inadequate to express my gratitude for the support I have always had from my parents Kenneth and Isabelle Abrahamian; my sister Jeanette; and my brother Ken, his wife Sue, and their children Kenny and Allyson. I hope they all know how much they mean to me.

Photographs by Ferdinand Boesch, unless stated otherwise.

Photographs by Alain Ekmalian: .

Diagrams by William Sayles

Copyright

Copyright 1986 by Mary Walker Phillips and William Sayles

Copyright 2013 by the Estate of Mary Walker Phillips

Appendix copyright 2013 by Patricia Abrahamian

Preface copyright 2007 by The New York Times. First published by The New York Times,

November 20, 2007. Reprinted by permission.

All rights reserved.

Bibliographical Note

This Dover edition, first published in 2013, is a new and expanded edition of the work originally published by Van Nostrand Reinhold Co., New York in 1971, revised edition published by Dos Tejedoras Fiber Arts Publications, St. Paul, Minnesota in 1986. A new Preface, Appendix, and color photos have been added to the Dover Edition.

International Standard Book Number

eISBN-13: 978-0-486-28754-6

Manufactured in the United States by Courier Corporation

49915401

www.doverpublications.com

Preface to the Dover Edition

The New York Times obituary written by Margalit Fox and published November 20, 2007, truly captured the essence of Mary Walker Phillips and the importance of her contribution to knitting.

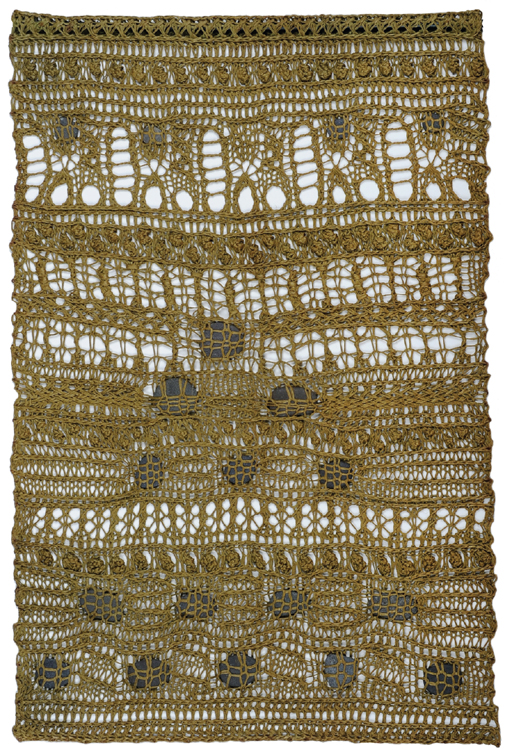

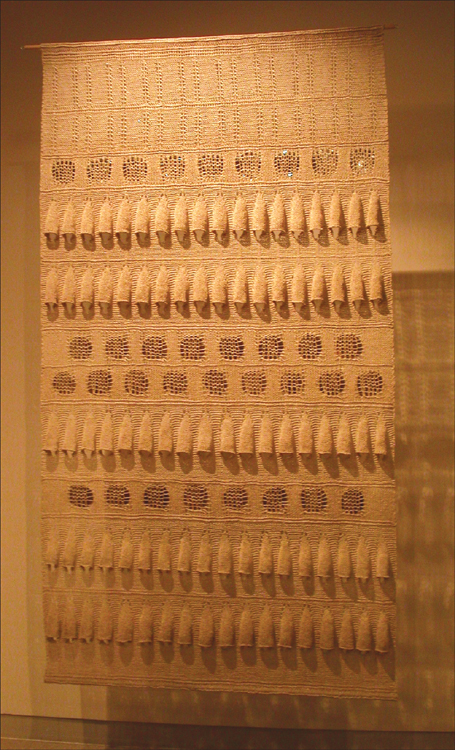

Mary Walker Phillips, a prominent textile artist, took the utilitarian craft of knitting and gave it bold new life as a modern art form to be displayed on the walls of museums around the world.

For centuries, knitting was a homey pastime, ideal for making sweaters, socks and hats. It was less a creative art than a re-creative one: womenfor it was nearly always a woman who wielded the needlestypically worked from printed patterns, following a set of instructions to produce a finished garment of predetermined design and dimensions.

By the mid-20th century, other textile traditions, like weaving, had crept into the realm of fine art, hung in galleries and reviewed seriously by critics. But knitting, consigned to the hearth, lagged far behind.

What Miss Phillips did, starting in the early 1960s, was to liberate knitting from the yoke of the sweater. Where traditional knitters were classical artists, faithfully reproducing a score, Miss Phillips knit jazz. In her hands, knitting became a free-form, improvisational art, with no rules, no patterns and no utilitarian end in sight.

Traditional materials also went out the window: where garment knitting generally involves wool or cotton, Miss Phillipss huge, abstract, diaphanous hangings might also use linen, silk, paper tape or fine metal wire. They sometimes incorporated materials like bells, seeds and bits of mica.

Considered one of the two or three most influential knitters of the second half of the 20th century, Miss Phillips was a fellow of the American Craft Council, an honor bestowed on only the most distinguished artisans. Exhibited worldwide, her work (which also includes avant-garde macram) is in the permanent collections of major museums including the Museum of Modern Art, the Cooper-Hewitt National Design Museum and the Art Institute of Chicago.

Mary Walker Phillips was born in Fresno on Nov. 23, 1923, to a prominent family descended from California pioneers. A traditional knitter in childhood, Miss Phillipsto the end of her life, she preferred Missbegan her artistic career as a weaver. After studying at the Cranbrook Academy of Art in Michigan, she worked in San Francisco and Switzerland, weaving fabric for clothing, upholstery and table linens. She later opened her own studio in Fresno.

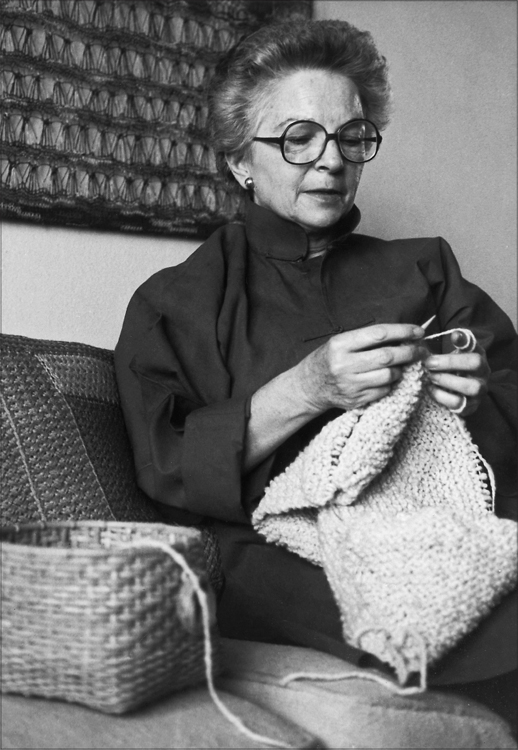

Mary Walker Phillips, 1985. (Photograph by Glenda Arentzen.)

Just how accomplished Miss Phillips was at the loom can been judged from a telegram she received in April 1948: Kindly bring cotton material for weaving thirty five yards drapes natural deep rose lavender and dark brown, also gold metallics.

It was signed Mrs. Frank Lloyd Wright. Miss Phillips spent three weeks at Taliesin West, the Wrights home in Scottsdale, Ariz., weaving the familys drapes and tablecloths.

In 1960, Miss Phillips returned to Cranbrook, completing her bachelors degree and, in 1963, earning a master of fine arts, concentrating in experimental textiles. Around this time, a friend, the noted fabric designer Jack Lenor Larsen, suggested she experiment with knitting as a medium for contemporary art.

Miss Phillips, who settled in New York in a yarn-filled apartment on Horatio Street, took up her needles once more. But what sprang from them was like no knitting ever seen. Using techniques that went beyond traditional knit and purl stitches, she created pieces that looked like delicate tapestries or vast expanses of lace, with transparent latticework, open areas and whorled textural patterns. Hung away from the wall and lighted well, her work threw off a dramatic counterpoint of shadows.

Next page