This book is dedicated to Seth Vidal. Seth didnt live long enough to see this book finished, but within it, a little piece of his hacker spirit will live on forever.

In April 2011 I was coming to the end of an executive MBA program at Cambridge and looking forward to spending some quality time with my wife, Liz. The old joke is that MBA stands for married but absent, and after two years of barely seeing each other, the last thing on our minds was jumping straight into another startup.

But after our accidental announcement of the Raspberry Pi educational computer project the following month (see sidebar), we had little choice but to knuckle down and make it happen. Liz, a freelance journalist by background, dropped everything to run our nascent community at www.raspberrypi.org . I, along with my colleagues at Broadcom and my fellow Raspberry Pi Foundation trustee Pete Lomas, started to figure out how to actually deliver the $25 ARM/Linux box that wed so rashly promised to build.

Funny Story

We went to see Rory Cellan-Jones at the BBC, in the hope that we might be able to use the dormant BBC Micro brand. He put a video of our prototype on his blog and got 600,000 YouTube views in two days. Theres nothing quite like accidentally promising over half a million people that youll make them a $25 computer to focus the mind.

Nine months later, we launched the Model B Raspberry Pi, taking 100,000 orders on the first day and knocking out both our distributors websites for a period of several hours. In the 18 months since then, weve sold nearly two million Raspberry Pis in over 80 countries.

So, how did our little educational computer, conceived as a way of getting a few hundred more applicants to the Computer Science Tripos at Cambridge, get so out of control? Without a doubt, the explosive growth of the Pi community has been thanks to the creativity and enthusiasm of hobbyists, who see the Pi as an easy way to connect sensors, actuators, displays, and the network to build cool new things. Where for the first year of the project Lizs blog posts described work that was being done by us as we struggled first to design the Pi and then to build enough of them to keep up with demand, today the vast majority of her posts are about what you have been doing with the Pi.

Its hard to pick favorites from the vast number of projects that weve seen and featured on the website. As an unreformed space cadet, the ones that stand out most in my mind are Dave Akermans high-altitude ballooning and Cristos Vasilass astrophotography experiments. Daves work in particular promises to put a space program within the budgetary reach of every primary school in the developed world and is part of a broader trend toward using the Pi to teach young people not just about computer programming, but about the whole range of STEM (science, technology, engineering, and mathematics) subjects. Another great development in this area was Mojangs decision at the end of 2012 to port Minecraft to the Pi, creating the scriptable Minecraft Pi Edition and spawning a large range of educational software projects.

As we head into 2014 and toward the second anniversary of the launch, were looking forward to seeing what you all get up to with the Pi. One thing is certain: it wont be anything I can imagine today.

Preface

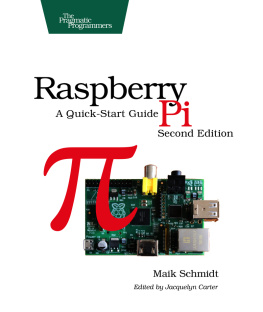

The inspiration for the Raspberry Pi was born when Eben Upton was working with computer science students at Cambridge University (see the for his own account). He saw a need for incoming students to have greater opportunities to obtain programming experience before they got to the university level. The first concept designs for what would become the Pi we know now were born in 2006. Alpha boards were demonstrated in late 2011, and the first 10 boards were auctioned off at the beginning of 2012, raising 16,000.

The first batch of 10,000 Raspberry Pis went on sale February 29, 2012. Toward the end of 2011, the SD card image for it had already been downloaded more than 50,000 times, hinting at its impending popularity. The two UK sellers at the time, Premier Farnell and RS Components, sold out within minutes, with the latter reporting more than 100,000 orders that day. Upton designed them for educationspecifically Python, hence the Pi part of the name. But the tiny board caught the eye of already-experienced programmers and electronics hackers. As of this writing, a year and a half after that first day of sale, more than two million have been sold.

And then roughly 1.95 million of them got stuck in an office drawer while their owners gathered with hackerspace friends over beer and collectively lamented, Yeah, I bought a Pi, but I havent figured out what to do with it yet. I was thinking I might use it to build a time machine and try to study the K-Pg event in person, but Ill probably just put XBMC on it.

We wrote this book for you, the ones who havent decided what to do with your languishing Pis yet. Of course, if you do just want to install XBMC, you can refer to on Twitter, and well let you know if we find a good source for flux capacitors.

Were in what we hope is still the early stages of a return to a DIY culture. Those of you deeply embroiled in it already, who have been to every Maker Faire and joined your local hackerspace the day it opened, might insist that, on the contrary, we are deep in the midst of said return. But it hasnt gone far enough yet. Beyond our little maker/hacker/builder/doer niche is still a wide world of disposable goods and electronics consumption and dump-tion. Our devices are increasingly designed to do what the designer intended without the flexibility to do what the owner intends, needs, or wants. Further, they often are sealed up boxes, keeping prying fingers from ripping them apart and rebuilding them to suit new visions.

The acceptance of closed, unhackable, unfixable goods is relatively new in the course of human culture. Its not so long agoperhaps even your own childhood if youre over 30 or soin which we were happily building our computers from kits and taking the TV to the repair shop instead of buying a new one. Devices like the Raspberry Pi help bring us back to that better time when we knew (or could find out) what was happening inside the things that we owned, when we could change them for the better and give them new life when they broke down.

The first chapter of this book is for everyone with a Raspberry Pi; it gives you a basis on which to build all of the hacks. From there, we move on to the larger projects that implement all of those smaller hack needs. And in the spirit of the Pis original purpose, we hope you learn a lot.

Who This Book Is For

Despite the potentially intimdating word hacks in the title, we dont expect you to be a Linux kernel developer or electrical engineer to be able to use this book. Hacks and hackingnot in the sense you hear those words used on the six oclock newsare how many of us learn best. Hands on, trying something new, possibly frying electronics in the process.

Weve tried to write these hacks so that even the novice can follow along and become a Raspberry Pi hacker. It will help greatly if you have at least a rudimentary understanding of how to use the Linux command line. For the most part, we walk you through those steps, too, but in places where we havent, a quick look to Google or to the man pages of a command should catch you up.

As to the electronics half of the hacking, weve tried to spell as much out in detail as possible. For those who already have a workroom filled with jumper wires and strange parts you picked up out of the electronics store clearance bin because they might be handy someday, this level of detail might feel belabored. Just skip ahead to the parts that are useful to you and be thankful that your less-knowledgeable friends will be getting help from the book instead of calling you to ask if GND is really that important, based on the assumption that its an amusing nod to their childhood and stands for Goonies Never (say) Die.