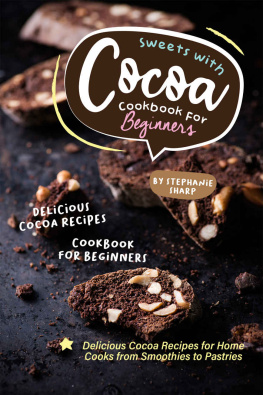

CONTENTS

The mingled scents of chocolate, vanilla, heated copper and cinnamon are intoxicating, powerfully suggestive; the raw and earthy tang of the Americas, the hot and resinous perfume of the rainforest. This is how I travel now, as the Aztecs did in their sacred rituals. Mexico, Venezuela and Colombia. The court of Montezuma. Cortez and Columbus. The food of the gods, bubbling and frothing in ceremonial goblets. The bitter elixir of life.Joanne Harris, Chocolat

Chocolate. No other food has the same beguiling, delicious pull on our senses. Almost magically, and alone among the things we eat, chocolate melts at around body temperature, flooding our mouth with voluptuous sweetness, an array of flavours and a whisper of bitterness as soon as we place it on our tongue. Its chemistry lights up the pleasure centres in our brain, energizes us and sates our hunger. But chocolate is more than just an edible delight.

Chocolate is nostalgia. A simple bite into a favourite bar can carry us back to our first childhood treat, that sweet reward for good behaviour or the comforting snack when we were sad. Chocolate is also full of contradictions. Its a balm for heartache yet also a symbol of love and desire. Its redolent of luxury, but more often than not produced by some of the poorest people in the world. It was revered by the ancients as a sacred gift from the gods, but legend also holds that chocolate was a powerful aphrodisiac that fuelled Casanovas orgies and empowered Montezuma to satisfy his harem. Over the years, chocolate has at once been hailed as wholesome, nourishing and medicinal, and also a vehicle for women to poison men and practise witchcraft.

Each bite of chocolate is imbued with history and flavoured with its epic journey over millennia from the rainforests of the Amazon, where the ancients first discovered how to prepare bitter cacao seeds, to the freshly minted bars stacked on supermarket shelves today. Chocolate is infused with politics and imperialism, economics and slavery, transport and technology, society and culture. It has fed the imaginations of artists from Salvador Dal to William Hogarth, and inspired writers from Samuel Pepys to Enid Blyton.

Globally, we now consume more than $US100 billion worth of chocolate confectionery every year, according to Euromonitor. But how did the bitter cacao bean become one of the worlds most adored foods?

The chocolate that we devour so eagerly today is a product of our age. Modern technology, integrated transport networks, global trade andbitter sweetlywar, slavery and colonial expansion, were needed to make it possible. Because, in the beginning, there was no chocolate, just the curious bulbous pods that dangled like vivid lanterns from the trunks of Theobroma cacao trees.

These distinctive plants originated in the lush cloud forests of the Upper Amazon. Archaeologists are learning more about humans long love affair with chocolate every day, but the most recent evidence suggests the Mayo Chinchipe-Maran people of modern-day Peru consumed cacao as far back as 3500 BC, probably as a drink made with maize and chilli. How they first came to unlock the magic of the bitter purple beans, we will probably never know exactly. Perhaps they copied the monkeys and squirrels they saw in the treetops, who ripped open the pods and devoured the pulp inside. But rather than toss away the seeds, as some animals did, the ancients discovered that by grinding them on a stonea tool they used to prepare many foodstuffsthey could transform the beans into a remarkably rich, sticky and aromatic paste: the first chocolate.

Humans eventually transported cacao north from the Amazon to Mesoamerica (which encompassed parts of modern day Central America and Mexico), where the Olmec people and then the Mayans developed a rich chocolate culture. Much of the mythology that surrounds the chocolate we eat today can be traced to the Mayans. These culturally advanced people, whose civilization flourished between AD 250 and 900, developed a hieroglyphic writing system to record their lives in gorgeously illustrated folding books (codices) and on ceramic vases, pots and drinking vessels. An abundance of these ceramics still exists, as well as four codices, all referencing and depicting cacao being harvested, prepared and consumed. Traces of theobromine, a chemical component of cacao that can survive for centuries, have also been found inside some vessels and on ceramics.

Aztecs preparing a beverage (possibly chocolate or coffee)

These artefacts confirm that cacao was much more than just a foodstuff to the Mayans and later the Aztecs: it was sacred and magical. Mayans believed cacao came from the Underworld and they placed it at the centre of their economic, political and ceremonial lives. The elite sipped cacao drinksboth green ones made from fresh pulp and others made from roasted and ground beansto seal marriage vows and to mark important life events like marriage and the birth of children. They also buried the drinks with the dead as sacred offerings to gods and patrons. Recent evidence suggests some of the ancients might have consumed cacao in food, as well.

The Mayans and Aztecs also used cacao beans as a form of currency. They dried and fermented the beans, which preserved them, and being small and light, they were ideal objects to transport and exchange. It was, in fact, on a Mayan trading canoe that Christopher Columbus first encountered cacao beans during his fourth and final voyage to the New World in 1502. But when he captured the vessel on Guanaja, an island of Honduras, he assumed the beans were almonds. Writing about the encounter in his diary later, Columbuss son Ferdinand observed that the Mayans placed a high value on what appeared to be prosaic objects: They seemed to hold these almonds at great price; for when they were brought on board ship together with their goods, I observed that when any of these almonds fell, they all stopped to pick it up, as if an eye had fallen. But Columbus thought nothing of the almonds and sailed away in search of gold. He had no way of knowing he had just become the first European to encounter cacao and had turned his back on one of the great gastronomical discoveries of all time.

It took another seventeen years, with the arrival of Spanish conquistador Hernn Corts and his forces in the New World in 1519, for Europeans to begin to understand the true importance of cacao. The Spanish noticed that the Aztecs used the beans as specific units of currency (one turkey was worth 100 beans, an avocado 3, and so on), and stored vast quantities in royal warehouses and strongholds (which the conquistadors duly plundered). The Mayans and Aztecs both used annatto, the seeds of the achiote tree, to colour their cacao drinks red to resemble blood, which had a central place in Mesoamerican cultures. Spanish observers also famously claimed that Aztec Emperor Montezuma II drank copious amounts of chocolate from golden goblets in bacchanalian fashion to seduce women. But historians say there is no evidence he drank chocolate for its supposed aphrodisiac qualities; its possible the drinks had simply fermented to the point of being alcoholic.