Tailor, 13201330, English

He is fashionably dressed in a loose surcote with peaked sleeves and fitchets (side slits) which give access to the belt and purse beneath. His fitted cote sleeves emerge at the wrists. He wears well-fitted hose and plain shoes; a loose hood with a long point is thrown back round his shoulders. He appears to be cutting out and shaping a cote, using a large pair of shears (probably exaggerated), and appropriating a remnant at the same time.

HoursoftheBlessedVirginMary,BritishLibraryMSHarley6563,f.65

First published 2001 in the United Kingdom by

Ruth Bean Publishers, an imprint of

The Crowood Press Ltd,

Ramsbury, Marlborough

Wiltshire SN8 2HR

www.crowood.com

This e-book first published in 2013

Sarah Thursfield and Ruth Bean 2001

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the prior permission of the publisher

ISBN- 9781847975836

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

Design Alan Bultitude

Photostyling Caryl Mossop

Photography Mark Scudder & Les Goodey

Digitalartwork Personabilia Design & Print, Higham Ferrers, Northants

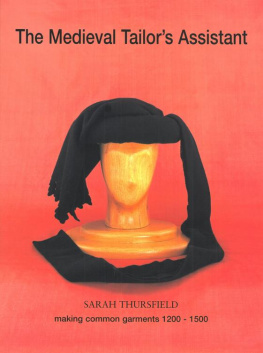

Cover

Modern version of the chaperon, mid 15th century

The classic chaperon, seen here in black broadcloth, is made up of three parts the liripipe and shoulder cape (gorget), which are sewn to a padded roll. The roll sometimes appears quite solid and may have been felted. The chaperon is often seen slung over the shoulder where it would stay in place with a long enough liripipe.

Contents

The intermediate

pattern;

I would like to thank the many people who have contributed to this book in different ways.

I am grateful to the late Janet Arnold, Dr Jane Bridgeman, Henry Cobb, Zillah Halls and Frances Pritchard for specialist advice, information and critical comments.

Many kind friends and customers have allowed me to test ideas and patterns, patiently acted as models, and provided stimulating discussion. They include Barbara and Len Allen, Jill Burton, Amanda Clark, Wayne and Emma Cooper, Carol Evison, Paul Harston, Jen Heard, the late Joy Hilbert, Paul Mason, Carrie-May Mealor, Matthew Nettle, Lindy Pickard, Elizabeth Reed, Penny and Kevin Roberts, Dave Rushworth, Matthew Sutton, Elaine Tasker, and Andrea Wright. I am indebted to them all; also to the Shropshire County Library who obtained help and information from far and wide; to my sister Ruth Gilbert (Beth the weaver), a ready source of advice; and to Mark Scudder and Les Goodey for their fine photographic work.

Without the unfailing support of my husband Nick, or his patient help together with my son Sam on the computer, this project could not have been launched. Without the experience and major contribution of Ruth and Nigel Bean, who brought it to its final form, it would not have been realized.

Photograph credits

Bibliothque nationale de France, Paris, Pl11; Bibliothque Royale Albert 1er, Bruxelles, Pls9,15; Bodleian Library, University of Oxford, cover (USA edition); the British Library, London, frontispiece, Pls5,17,18; Stedlijke Musea, Brugge, Pl16; Cambridge University Library, Photography Department, cover (UK edition), Pls1-4,6-8,10,12-14,19.

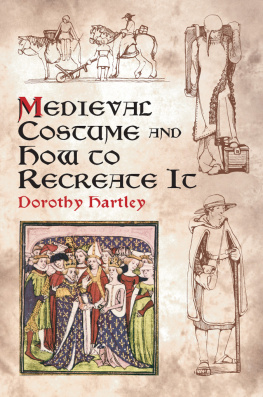

During the years I have been making historical garments I have been especially drawn to the dress of the later middle ages. We can see in the contemporary images of dress, now our main source of information, the features which give the period such appeal bright colours, flowing fabrics, the contrasting styles of simple working dress and the elaborate, sumptuous clothes of the nobility. But the images tell us little about how the clothes were made: evidence is limited compared with later periods, from which more garments and documents have been preserved.

So the challenge for the dressmaker today is how to recreate the look of the period. I have tried to achieve this firstly by using visual sources like effigies and brasses, wall hangings, paintings, and illuminated manuscripts as models. Then, by applying experience of traditional sewing techniques and modern tailoring and of course much experiment I have prepared working patterns for a range of garments. I have aimed to achieve the look and fit of the time, in a way that is practicable, for the modern sewer. As for the method, it is my own interpretation of the evidence I have seen. Others may interpret their sources differently, and further research may in time increase our limited knowledge. But many people have asked me for patterns and I believe this practical guide to the cut and construction of common garments will fill a need and perhaps stimulate enquiry.

The book is intended for anyone wishing to reproduce historical dress, for re-enactment, displays, drama or personal use. It is assumed that the reader has a basic knowledge of dressmaking. The instructions throughout aim at the high standard of hand finishing appropriate for living history, but the reader may equally use modern techniques. The garments are presented, with brief notes on their historical background, in three main layers: underwear, main garments, and outer garments, for men, women and children. Head-wear and accessories are covered separately. Examples of the basic forms are included for each garment, and most are followed by their later or more elaborate styles. Initial guidance is given in Howtousethebook, and detailed instructions on techniques, planning and materials are provided and referred to throughout. Garments are drawn mainly from English and West European sources, though the selection could include only some of the many variations in style that existed.

Several types of illustration are used for each garment. They include drawings from historical sources, with modern style drawings to model the period look. Patterns, cutting layouts, and enlarged details then allow personal working patterns to be planned, cut and made up. Photographs show several finished garments and details of techniques.

Readers new to historical dressmaking and re-enactment will find that the conditions and practice of tailoring were very different then from today. Clothes, like other possessions, were fewer and valuable. They would be painstakingly made, often by craftsmen, well maintained, and expected to last and be passed on. They were also important in reflecting the wearers status. The different idea of fit and the different tailoring and sewing techniques, which were all part of the period look, are covered in the introductory chapters. Take time if you can to explore the period and its dress. This will add to your enjoyment as you make the garments and will help you to qualify as a medieval tailors assistant!

The instructions are intended for readers with basic dressmaking skills. Beginners are advised to use a modern dressmaking manual or, better still, work with an experienced sewer or a teacher.