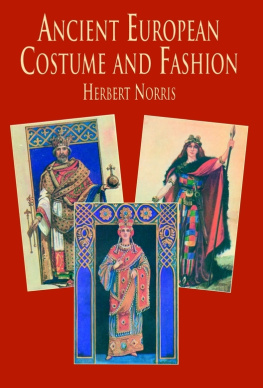

MEDIEVAL COSTUME

and How to Recreate It

DOROTHY HARTLEY

With an Introduction and Notes by

FRANCIS M. KELLY

DOVER PUBLICATIONS, INC.

Mineola, New York

Illustration on Title Page

THE TAILOR CUTTING OUT [B.M. MS. Harl. 6563, 14c.]

Bibliographical Note

This Dover edition, first published in 2003, is an unabridged republication of Medival Costume and Life, originally published by Charles Scribners Sons, New York, and B. T. Batsford, Ltd., London, in 1931.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Hartley, Dorothy.

[Mediaeval costume and life]

Medieval costume and how to recreate it / Dorothy Hartley; with an introduction and notes by Francis M. Kelly.

p. cm.

Originally published: Mediaeval costume and life. New York: Charles Scribners Sons; London: B.T. Batsford, 1931.

Includes index.

ISBN-13: 978-0-486-42985-4 (pbk.)

ISBN-10: 0-486-42985-7 (pbk.)

1. CostumeHistoryMedieval, 5001500. 2. CostumeGreat BritainHistory. 3. Great BritainSocial life and customs1066-1485. 4. Civilization, Medieval. I. Kelly, Francis Michael, 1879-1945. II. Title.

GT732.H37 2003

391'.00942dc22

2003055775

Manufactured in the United States by Courier Corporation

42985706

www.doverpublications.com

INTRODUCTION

PYGMALION ENJOYS LACING UP GALATEA

[Bodl. Liby. MS. Romaunt de la Rose, 15c.]

UNLESS I am much deceived, interest in the apparel and general outward appearance of our ancestors is gradually growing at once more widespread and more intelligent than in any previous era. I would specially underline this word intelligent; since, particularly from the Romantic movement of the early nineteenth century, there has long existed a vast deal of half-baked Schwarmerei in connection with the good old times in all their supposed accidental outward manifestations. It went hand in hand with indifference to, if not aversion from, the unvarnished truth of historic record, as much from intellectual indolence as from ignorant conceit. It found expression chiefly in fancy-dress balls and parties and in so-called historic pageants, such as made fearful the years before the War. Considered merely as a social pastime it is harmless enough in all conscience: it affords a number of leisured folk an excuse for gratifying an innocent vanity and for imposing upon their neighbours reluctance to say No.

We cannot, I regret to say, as yet declare: nous avons chang tout cela; it is neither likely nor specially important that Society should ever be denied the right of entertaining itself in the spirit it finds most amusing. Fancy-dress need after all be no more than its name implies; glaringly inaccurate historic pageants have on the other hand no excuse for their being. All too late it is beginning to be realized, slowly indeed but no less surely, that the historic evolution of dress and personal ornament offers a wide field for methodical study; that it is in fact a science and can be made to subserve worthier ends than those of mere amusement. In its degree the dress of the past is no less the outward reflection of its age than, say, architecture, and its educational value should be hardly less. Indeed it is perhaps scarcely too much to say that we shall but imperfectly apprehend the true inwardness of many events and personalities as long as we are unable to visualize them in their proper habit and surroundings. From the purely educational point of view, historic truth is no less desirable in this department than in any other. In this respect the stage and, above all, the cinema have unlimited possibilities if rightly directed. Actually the travesties often served up to the public are too glaring to be even funny.

The value of a good grounding in the history of costume does not stop here. It is one of the most valuable means we possess in assessing the value of artistic attributions. In old genre painting, and especially in portraiture, innumerable are the instances where it might well prove the determinant argument for or against a suggested identification. In a recent book-review I read:... many a false datal attribution in the world of collecting might have been obviated by a precise knowledge of bygone dress; and elsewhereFor them [sc. art-critics] a nice knowledge of humdrum details, of sleeves or curls or cravats, would be a godsend, as an aid to and corrective of intuition. This was a cardinal preceptscarcely remembered, much less followedof the late Sir George Scharf. But of recent years, mainly on the Continent, yeoman service has been done by (among others) Messrs. Adrien Harmand, Paul Post, F. van Thienen and Mmes. E. de Jonghe, Helne Dihle and Ottilie Rady. Even heraldic indications are a far less reliable index than costume, since they may well, even where they are old, have been added aprs coupa relatively easy matter. It would require no very profound study of costume to save the intending collector in many cases from wasting money on rank impostures.

While we are not so unreasonable as to expect the average person to have leisure or a taste for antiquarian researches, he on his part has a right to look for clear-cut and accurate guidance from those who presume to put him wise in this as in any other department of knowledge. Vague generalities such as fill the usual run of costume-books are apt to be of very little use as soon as definite detailed information is sought on any particular point. It is a wholesome experience for the would-be expert to be compelled to answer off-hand the questions of the ordinary man in the street. It will do him good to realize how unprepared he often is to deal with problems which suggest themselves quite naturally to his unsophisticated neighbour. He will never learn anything worth knowing till his own abysmal ignorance is brought home to him. For the ordinary reader it is a difficult matter to pick and choose from the heterogeneous mass of matter offered for his consideration. We have therefore a right to demand that the guide-books to which he is referred should supply no information that is not accurate, methodical and clear-cut.

It is a thoroughly unsound, though very common, practice in books on English costume to partition off particular modes by reigns, as if in so many watertight compartments. One particular type of dress is treated as characteristic of the whole of a particular reign and no other. Thus Charles I, whether at his marriage to Henrietta Maria (1625) or on trial at the bar of the House of Commons (1649), must borrow his wardrobe from van Dyck. It so happened that that artists residence at Court (1632-41) corresponded almost exactly with one of the most elegant ensembles of masculine attire that ever fashion evolved, but one equally alien to the starched and corseted figures of Buckinghams day and the ungainly deformations that came into vogue during the Civil Wars.

As Miss Hartley has aptly insisted, before attempting to reconstruct in our minds eye the outward appearance of our forebears it is necessary to familiarize oneself pretty accurately with the general surroundings in which they moved and had their being. Account must be taken of their position in the social scheme, of age, place, season and the particular circumstances that govern their activities. In our present age of progress a certain drab uniformity seems more and more to be the mark of at least the male sex. Except on formal occasions there is nothing whereby we may tell a duke from an