A History of the Paper

Pattern Industry

A History of the Paper

Pattern Industry

The Home Dressmaking Fashion Revolution

JOY SPANABEL EMERY

Bloomsbury Academic

An imprint of Bloomsbury Publishing Plc

| 50 Bedford Square | 1385 Broadway |

| London | New York |

| WC1B 3DP | NY 10018 |

| UK | USA |

www.bloomsbury.com

Bloomsbury is a registered trade mark of Bloomsbury Publishing Plc

First published 2014

Joy Spanabel Emery, 2014

Joy Spanabel Emery has asserted her right under the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act, 1988, to be identified as Author of this work.

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or any information storage or retrieval system, without prior permission in writing from the publishers.

No responsibility for loss caused to any individual or organization acting on or refraining from action as a result of the material in this publication can be accepted by Bloomsbury or the author.

British Library Cataloguing-in-Publication Data

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

ISBN: 978-1-4725-7746-7

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

A catalogue record for this book is available from the Library of Congress.

Contents

Chapter 1

Chapter 2

Chapter 3

Chapter 4

Chapter 5

Chapter 6

Chapter 7

Chapter 8

Chapter 9

Chapter 10

Chapter 11

Chapter 12

Appendix

Chapter 6

Chapter 9

Chapter 11

T his book is the result of many years of searching though dusty pattern catalogs, fashion magazines, and thousands of patterns. The work was pioneered by Betty Williams, who began laboriously piecing together the history of the numerous pattern companies started in the nineteenth century. She attracted other researchers in her quest, most notably Kevin L. Seligman and me, encouraging us to augment the work she had begun.

A large number of people have contributed to the work in a variety of ways: Kevin Seligman, author, with his expertise on mens tailoring and English pattern companies; from the University of Rhode Island, Sarina Rodrigues, Special Collections, with guidance and support; and Linda Welters and Margaret Ordoez, Department of Textiles, Fashion Merchandising and Design, with photographic assistance and editorial support. I am grateful as well to Susan Hannel of the Department of Textiles, Fashion Merchandising and Design for taking on the challenge of revising and rendering the patterns in the appendix, and to Claire Shaeffer, freelance author and teacher, for providing important information through her research on pattern company practices over the last forty years. For assistance in obtaining permissions from the pattern companies, I thank Patricia DeSimone of Wilton Brands LLC for Simplicity and Burda and Kathleen Wiktor for McCall, Butterick, Vogue, and Kwik Sew. I am indebted to Roberta Hale, master seamstress, for numerous volunteer hours in the archive and reproductions of small-scale garments from a variety of patterns included in the illustrations. I have special thanks for Whitney Blausen for patiently reading through many versions of the text and challenging me for clarification.

Finally thanks to the editorial team at Bloomsbury: Anna Wright, editor, and Hannah Crump, publishing assistant, for fielding an endless string of e-mails, and Abbie Sharman, editorial assistant, design.

Joy Spanabel Emery

Commercial Pattern Archive

University of Rhode Island

Kingston, Rhode Island

Copyright Disclaimer

The author and publishers gratefully acknowledge the permissions granted to reproduce the third-party copyright materials contained in this book.

Every reasonable effort has been made to trace copyright holders and to obtain their written permission for the use of copyright material. The author and publisher apologize for any errors or omissions in the copyright acknowledgments contained in this book and would be grateful if notified of any corrections that should be incorporated in future reprints or editions of this book.

Significance

W hen Western clothing began to reveal the shape of the body in the twelfth century, cloth needed to be cut into shapes and the shapes became more complex in each century, thus requiring guides or patterns to form appropriate shapes to fit the body. The paper pattern ultimately became that guide; however, as Frieda Sorber observed in the exhibition catalog Patterns from the MoMu in Antwerp, The history of the paper pattern is almost as elusive as the ephemeral nature of the object itself (Heavens 2003: 23).

This book is intended to dispel much of the mystery of the history of patterns and the companies that produced them, with a brief history covering both. The research is based upon publications and tissue patterns primarily from the United States and the United Kingdom. There are numerous cultural facets open for further research and analysis. This introduction is a challenge for further exploration.

It is a fascinating story. The struggles and maneuvers are a microcosm of late nineteenth- and twentieth-century business practices. Beginning with antecedents from the Renaissance with the rise of tailoring, the story traces the history of patterns and the pattern companies from the introduction of dressmaker patterns in the 1840s to the present.

The study of patterns belies two persistent myths about dress patterns. One is the concern about how fragile the patterns are. By and large the tissue paper patterns are not as fragile as they appear primarily because the tissue is usually acid-free paper like that used to wrap fruit (Williams and Emery 1996). Therefore, many patterns have survived, providing excellent historical documentation. Another myth is the concept that the patterns are out of date by the time they reach the customer. Repeated evidence shows that the latest styles were available in a very timely manner. For example, the introduction of Mary Quants miniskirt in 1965 spurred a bit of a crisis as pattern companies and ready-to-wear retailers alike scrambled to determine where hem length would settle. Pattern companies stayed up to date with the style and met the demand.

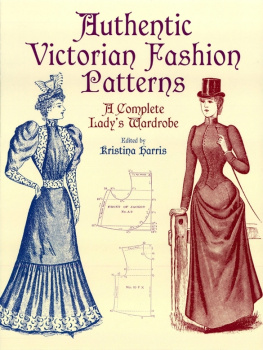

With easy and rapid distribution of the latest styles, a skilled needlewoman could aspire to produce the latest styles. With the aid of such fashion magazines as Godeys, Petersons, and Leslies, the sewing machine, and greater accessibility to dress patterns by such entrepreneurs as Mme Demorest, Ebenezer Butterick, and James McCall, women could make fashionable as well as serviceable garments. Thus, patterns are credited with the democratization of fashion (Walsh 1979; Paoletti 1980).

Patterns evoke an intimate picture of popular culture and social history, the most immediate being the evolution of fashionable styles primarily for women and children. The styles are for everyday wear. Garments that are saved and preserved in museum collections are primarily high fashion or special occasion garments for an elite few. Patterns provide a detailed, unique record of the evolution of everyday styles from the 1840s to the present. They follow the evolution of fabrics for clothing, revealing the popularity and influence of new synthetics, such as rayon in the 1930s or polyester knits in the 1970s.

Next page