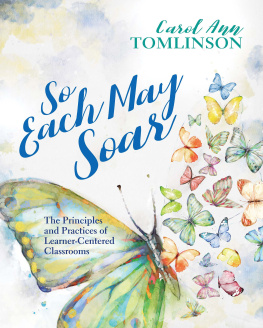

How To Differentiate Instruction in Academically Diverse Classrooms, 3rd Edition

Carol Ann Tomlinson

Table of Contents

Publisher's note: This e-book has been formatted for viewing on e-reading devices. If you find some figures hard to read on your device, try viewing through the Kindle for PC (www.amazon.com/gp/kindle/pc) or Kindle for Mac (www.amazon.com/gp/kindle/mac) applications on your laptop or desktop computer.

ASCD 2017

Preface to the Third Edition

....................

Teaching is difficult.

Teaching really well is profoundly difficult.

Even the best among us fall short of our professional aspirations regularly, and feel diminished in those moments.

And yet, for many, the work of teaching is also nourishing. It grows us as we grow the young people in our care. Each success is instructive. Each failure is instructive. We are challenged to become the best version of ourselves as we challenge our students to become their best as well.

One classroom reality that taxes our capacity to teach as we need and want to teach is the great variety of learners who surround us every day. They are mature and immature for their age. They are supported too enthusiastically at home and not supported at all. They are excited by school and terrified by it. They suffer from poverty and from affluence. They are entitled, and they are without hope. They are socially adept and socially inept. They are intrigued, inspired, and shut down by very different topics or issues.

Our students come to us with an array of challenges: physical, cognitive, emotional, and economic. Some have been diagnosed with attention deficit disorder or autism spectrum disorder. About 8 percent of teens have been diagnosed with anxiety disorders (Prentis, 2016), and many more suffer anxiety without a diagnosis. Approximately 62 percent of students with disabilities spend 80 percent or more of the school day in general education classes (Office of Special Education & Rehabilitative Services, 2015). About half of our students qualify for free and reduced-price luncha common marker of economic stress (Blad, 2015).

Our students also come to us with highly advanced skills and understandings in one subject, or in many. They may represent a wide array of cultures that vary in significant ways. Many speak other languages more confidently than they speak the language of the classroom. Race is a confounding factor for many learners. Too many students bring with them to school stresses from home that are too great for young shoulders to carry. Many students, of course, represent several of these realitiesa very bright student whose learning disability masks his promise, a second-language learner whose family teeters on the edge of economic viability, a child battered by life and cloaking great academic possibilities that are hidden in equal measure from others and from self.

And at varied points, virtually every learner is weighed down by peer concerns, encounters crippling loss, is distracted by the demands of growing up, struggles with unspoken fears, and feels lost in one way or another. Each of those realities impacts learninga statement that neither the science nor the common sense of teaching finds worthy of debate. Thus it would seem that to teach wellto teach so that learning enlivens the learneris to teach with the intent to be attuned to, and to attend to, the variance before us.

Differentiation suggests it is feasible to develop classrooms where the reality of learner variance can be addressed along with curricular realities. Not that it is easy, but that it is feasiblejust as it was and continues to be feasible for teachers in one-room schoolhouses, for teachers in multigrade classrooms, and for teachers in a broad range of more "contemporary" contexts in the United States and internationally who differentiate instruction as a way of life in their classrooms.

The idea is compelling. It challenges us to draw on our best knowledge of teaching and learning. It suggests that there is room for both equity and excellence in our classrooms.

As "right" as the approach we call differentiation seems, it promises no slick and ready solutions. Like most worthy ideas, it is complex. It calls on us to question, change, reflect, and change some more. How to Differentiate Instruction in Academically Diverse Classrooms follows this evolutionary route. In the years since the first and second editions, I have had the benefit of accumulating probing questions and practical examples from many educators as well as the continual study of findings from research in both education and neuroscience. This revision reflects an extension and refinement of the elements presented in the earlier versions of the book, based in no small measure on dialogue with other educators.

The title change from the book's initial version, How to Differentiate Instruction in Mixed-Ability Classrooms , to its third edition version, How to Differentiate Instruction in Academically Diverse Classrooms , also represents an evolution in my thinking and in contemporary classrooms. Demographic changes suggest that we must be deeply engaged with creating classrooms that work well for students whose learning may affected by culture, language, race, and poverty as well as by academic performance. In addition, I have become more and more troubled by our inclination to conclude that a student or group of students is "smart" or "not smart" and to separate and teach them accordingly. While it is doubtless the case that there is a range of learning capacities in any classroom or school, it is equally the case that we are poor judges of the level of possibility that abides in any student. The presumptive "ability" we assign to a student too often becomes a sort of pedagogical predestination. I hope the title change is a reminder to all of us who are educators to teach all comers with the respect, enthusiasm, and optimism that we hunger for our own children to experience in their classrooms.

I am grateful to ASCD for the ongoing opportunity to share reflections and insights fueled by many educators who work daily to ensure a good academic fit for each student who enters their classrooms. These teachers wrestle with standards-driven curriculum, grapple with a predictable shortage of time in the school day, do battle with management issues in a busy classroom, and fight against the test mania that reduces learning to particles of dust. These educators also derive energy from the challenge and insight generated by their students. I continue to be the beneficiary of their frontline work. I hope this small volume represents them well. I hope also that it clarifies and extends what I believe to be an essential discussion about how (not whether) we can attain the ideal of a high-quality public education that exists to maximize the capacity of each learner in our careeach learner who must trust us to direct the course of his or her learning.

Introduction

....................

Bill Bosher, a former Superintendent of Education for Virginia, was fond of saying that the only time there was any such thing as a homogeneous classroom was when he was in the room by himself. He would follow this statement with a longish pause and a questioning browthen, "and come to think of it, I'm not even sure about that ."