T HE S EA

AND

THE J UNGLE

An Englishman in Amazonia

T HE S EA

AND

THE J UNGLE

An Englishman in Amazonia

H. M. TOMLINSON

Dover Publications, Inc.

Mineola, New York

Bibliographical Note

This Dover edition, first published in 2015, is an unabridged republication of The Sea and the Jungle, originally published by Duckworth & Co., London, in 1912.

International Standard Book Number

eISBN-13: 978-0-486-80397-5

Manufactured in the United States by Courier Corporation

79573X01 2015

www.doverpublications.com

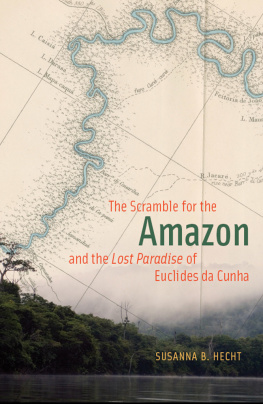

THE SEA AND THE JUNGLE

Being the narrative of the voyage of the tramp steamer Capella from Swansea to Par in the Brazils, and thence 2000 miles along the forests of the Amazon and Madeira Rivers to the San Antonio Falls; afterwards returning to Barbados for orders, and going by way of Jamaica to Tampa in Florida, where she loaded for home. Done in the years 1909 and 1910.

DEDICATED TO THOSE WHO DID NOT GO

CONTENTS

THE SEA AND THE JUNGLE

ONE

T HOUGH it is easier, and perhaps far better, not to begin at all, yet if a beginning is made it is there that most care is needed. Everything is inherent in the genesis. So I have to record the simple genesis of this affair as a winter morning after rain. There was more rain to come. The sky was waterlogged and the grey ceiling, overstrained, had sagged and dropped to the level of the chimneys. If one of them had pierced it! The danger was imminent.

That day was but a thin solution of night. You know those November mornings with a low, corpse-white east where the sunrise should be, as though the day were stillborn. Looking to the dayspring, there is what we have waited for, there the end of our hope, prone and shrouded. This morning of mine was such a morning. The world was very quiet, as though it were exhausted after tears. Beneath a broken gutter-spout the rain (all the night had I listened to its monody) had discovered a nest of pebbles in the path of my garden in a London suburb. It occurs to you at once that a London garden, especially in winter, should have no place in a narrative which tells of the sea and the jungle. But it has much to do with it. It is part of the heredity of this book. It is the essence of this adventure of mine that it began on the kind of day which so commonly occurs for both of us in the years assortment of days. My garden, on such a morning, is a necessary feature of the narrative, and much as I should like to skip it and get to sea, yet things must be taken in the proper order, and the garden comes first. There it was: the blackened dahlias, the last to fall, prone in the field where death had got all things under his feet. My pleasance was a dark area of soddened relics; the battalions of June were slain, and their bodies in the mud. That was the prospect in life I had. How was I to know the skipper had returned from the tropics? Standing in the central mud, which also was black, surveying that forlorn end to devoted human effort, what was there to tell me the skipper had brought back his tramp steamer from the lands under the sun? I knew of nothing to look forward to but December, with January to follow. What should you and I expect after November, but the next month of winter? Should the cultivators of London backs look for adventures, even though they have read old Hakluyt? What are the Americas to us, the Amazon and the Orinoco, Barbados and Panama, and Port Royal, but tales that are told? We have never been nearer to them, and now know we shall never be nearer to them, than that hill in our neighbourhood which gives us a broad prospect of the sunset. There is as near as we can approach. Thither we go and ascend of an evening, like Moses, except for our pipe. It is all the escape vouchsafed us. Did we ever know the chain to give? The chain has a certain lengthwe know it to a linkto that ultimate link, the possibilities of which we never strain. The mean range of our chain, the office and the polling booth. What a radius! Yet it cannot prevent us ascending that hill which looks, with uplifted and shining brow, to the far vague country whence comes the last of the light, at dayfall.

It is necessary for you to learn that on my way to catch the 8.35 that morningit is always the 8.35there came to me no premonition of change. No portent was in the sky but the grey wrack. I saw the hale and dominant gentleman, as usual, who arrives at the station in a brougham drawn by two grey horses. He looked as proud and arrogant as ever, for his face is as a bulls. He had the usual bunch of scarlet geraniums in his coat, and the stationmaster assisted him into an apartment, and his footman handed him a rug; a routine as stable as the hills, this. If only the solemn footman would, one morning, as solemnly as ever, hurl that rug at his master, with the umbrella to crash after it! One could begin to hope then. There was the pale girl in black who never, between our suburb and the city, lifts her shy brown eyes, benedictory as they are at such a time, from the soiled book of the local public library, and whose umbrella has lost half its handle, a china knob. (I think I will write this book for her.) And there were all the others who catch that train, except the young fellow with the cough. Now and then he does miss it, using for the purpose, I have no doubt, that only form of rebellion against its accursed tyranny which we have yet learned, physical inability to catch it. Where that morning train starts from is a mystery; but it never fails to come for us, and it never takes us beyond the city, I well know.

I have a clear memory of the newspapers as they were that morning. I had a sheaf of them, for it is my melancholy business to know what each is saying. I learned there were dark and portentous matters, not actually with us, but looming, each already rather larger than a mans hand. If certain things happened, said one half the papers, ruin stared us in the face. If those things did not happen, said the other half, ruin stared us in the face. No way appeared out of it. You paid your halfpenny and were damned either way. If you paid a penny you got more for your money. Boding gloom, full-orbed, could be had for that. There was your extra value for you. I looked round at my fellow passengers, all reading the same papers, and all, it could be reasonably presumed, with foreknowledge of catastrophe. They were indifferent, every one of them. I suppose we have learned, with some bitterness, that nothing ever happens but private failure and tragedy, unregarded by our fellows except with pity. The blare of the political megaphones, and the sustained panic of the party tom-toms, have a message for us, we may suppose. We may be sure the noise means something. So does the butchers boy when the sheep want to go up a side turning. He makes a noise. He means something, with his warning cries. The driving uproar has a purpose. But we have found out (not they who would break up side turnings, but the people in the second-class carriages of the morning train) that now, though our first instinct is to start in a panic, when we hear another sudden warning shout, there is no need to do so. And perhaps, having attained to that more callous mind which allows us to stare dully from the carriage window though with that urgent din in our ears, a reasonable explanation of the increasing excitement and flushed anxiety of the great Statesmen and their fuglemen may occur to us, in a generation or two. Give us time! But how they wish they were out of it, they who need no more time, but understand.

I put down the papers with their calls to social righteousness pitched in the upper register of the tea-tray, their bright and instructive interviews with flat-earthers, and with the veteran who is topically interesting because, having served one master fifty years, and reared thirteen children on fifteen shillings a week, he has just begun to draw his old-age pension. (Theres industry, thrift, and success, my little dears!) One paper had a column account of the youngest child actress in London, her toys and her philosophy, initialed by one of our younger brilliant journalists. All had a society divorce case, with sanitary elisions. Another contained an amusing account of a man working his way round the world with a barrel on his head. Again, the young prince, we were credibly informed in all the papers of that morning, did stop to look in at a toy-shop window in Regent Street the previous afternoon. So like a boy, you know, and yet he is a prince of course. The matter could not be doubted. The report was carefully illustrated. The prince stood on his feet outside the toy shop, and looked in.