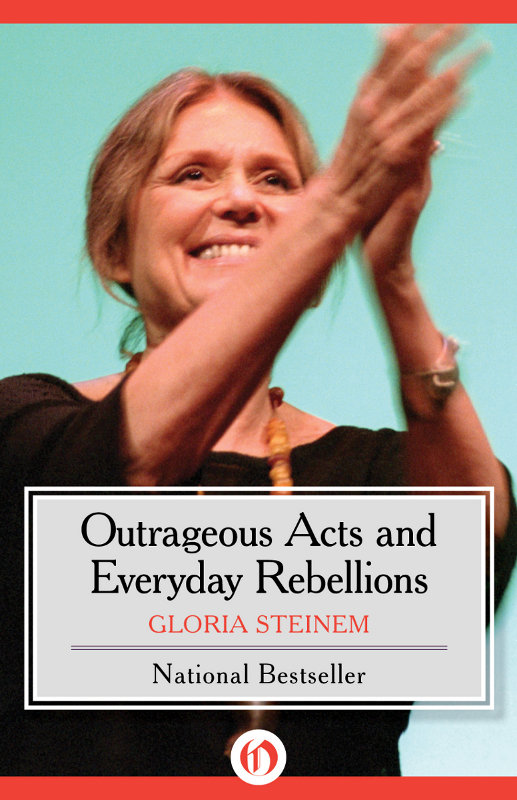

Outrageous Acts and Everyday Rebellions

Gloria Steinem

This book is gratefully dedicated to

Letty Cottin Pogrebin, who went through boxes of past writing, sold a sampling to Holt, and thus forced me to work on this book; to Suzanne Braun Levine, who gave loving and time-consuming advice on what to keep and where to put it; to my editor, Jennifer Josephy, whose good judgment is matched only by her great patience; to Joanne Edgar, who has spent a dozen years encouraging me to make space for writing, even when I didnt do it; to Robin Morgan, whose sisterly critiques I hope I never have to live without; to Robert Benton, whose long-ago listening to stories of a Toledo childhood helped show me that I neednt pretend to be someone else to be a writer; to Clay Felker, who never cared what gender of journalist a newsworthy idea came from; to the Woodrow Wilson International Center for Scholars at the Smithsonian Institution, whose fellowship provided time for most of the research herein; to Stan Pottinger for eight years of friendship, encouragement, and vitality; to Alice Walker for an honesty so strong that it lights an honest path for those around her; to Andrea Dworkin for an anger so righteous that it keeps others from confronting injustice without it; to Patricia Carbine, my friend and partner at Ms. magazine, who has given me and millions of others a forum for new ideas and dreams; to my father, Leo Steinem, who taught me to love and live with insecurity; to my mother, Ruth Nuneviller Steinem, who performed the miracle of loving others even when she could not love herself; and to all the courageous people I have met in twenty years of reporting and organizingthose women and men who dream of a justice that has yet to come and live on the edge of history.

Note to the Reader

WITHIN THE TEXT OR at the end of the article, you will find the year it was written. When related articles have been combined into one, the year of each has been included. Where there have been updates for this second edition, they also follow at the end of an essay. To allow each essay to stand on its own, some facts have been referred to more than once, but I have tried to minimize overlap, and to restore or rewrite text that was adapted for a particular magazine issue. Two essays, Life Between the Lines and Ruths Song (Because She Could Not Sing It), appeared here for the first time, as do the Preface and Postscripts, and other updating in this second edition. In general, Ive tried to make this book an entity in itself, without changing the state of mind in which each of its various parts was written.

Preface

AS A WRITER, I feel rewarded by the fact that this collection has remained in print over the dozen years since it was first published. Now, with a new preface and a few postscripts, it enters its second edition. Considering the average shelf life of a book in this country is somewhere between that of milk and eggsand the essays in this one ranged over a twenty-year period when they were first assembledthat is more than I could even have imagined.

Reissued in a slightly changed world, I hope these essays have added uses. For younger readers and others whose idea of the recent feminist past is secondhand, they may contribute to an account of events and ideas as they were experienced at the time. I think of the need for such a contemporaneous record whenever I read books and articles that are based more on media or academic accounts than on the diverse experiences of people who were there; for instance, when I hear women-imitating-men, anti-male, women-as-victims, white middle class, and other mutually contradictory descriptions of a monolithic movement I dont recognize. Even feminist scholars sometimes fall victim to the ease of computer searches, and let their views be shaped by newspaper clippings they wouldnt trust in the present. Perhaps there should be a guideline for all scholars of the recent past: People before paper.

I also hope the durability of this and other collections and anthologies puts a dent in the popular convention that multisubject books are somehow less worthwhile and lasting than single subject ones. When I was writing Life Between the Lines, I, too, felt apologetic for not producing what I still thought of as a real book. Since then, Ive learned that diversity has its uses, especially when trying to convey even a little of what happens when we transform ideas once based on sex and race. It turns out that, for every purpose other than reproduction on one hand or resistance to certain diseases on the other, the differences between people of the same sex or race are much greater than those between females and males, or between races as groups; yet lifelong caste systems based on these two visible differences remain the only political systems so pervasive that they are confused with nature. One subject just isnt enough to excite our imaginations of what life could be like without all the assumptions that flow from these caste systems, from an intimate to a global level. Even histories of movements against such caste systems are more about the thing than the thing itself. Only personal stories, plus parallels with systems already recognized as politicalsay, those based on class or ethnicity, which also were once thought to be inborncan help us begin to see the world as if everyone mattered. After all, human beings do what we see, not what were told. We need diverse examples.

In retrospect, I realize that I also responded to the what-one-book-should-I-read-about-feminism question by recommending books that offered diversity, from anthologies like Sisterhood Is Powerful, Radical Feminism, and All the Women Are White, All the Blacks Are Men, But Some of Us Are Brave, to collections by one author, like Andrea Dworkins Woman Hating or Alice Walkers In Search of Our Mothers Gardens. Of those, Robin Morgans Sisterhood Is Powerful holds the record for longevity in this wave of feminism with twenty-five years in print, and the rest are still in bookstores, dog-eared in libraries, assigned in classrooms, or cherished at bedsidealong with other treasure troves that have appeared in the meantime. (Note: There are more references for that what-one-book-should-I-read-about-feminism listed at the end of this preface. Each book will lead you to many more.) If this collection joins them in any of those places, Ill be a happy writer.

On the other hand, the activist in me doesnt feel at all happy to find that this or any of its sister books is still relevant. I would feel far more rewarded if this collection were so out of date with most readers that it ranked with Why Roosevelt Cant Win A Second Term, or the cottage industry of books about South African apartheid and Soviet Communism as systems only wars could end. When I see the essays in this book being handed down to another generation of readers, I dont know whether to celebrate or mourn.

Here are some examples of their currency that worry me:

Recently, I was interviewed for a television documentary on the womens movement that focused on why, in the words of its women producers, there are no young feminists. Though they could have looked at opinion polls and found there are actually more young feminists than ever before in historynot to mention more young women who lead feminist lives, whatever they call themselvesI knew what they meant. Their question really was: Why arent young women more

Next page