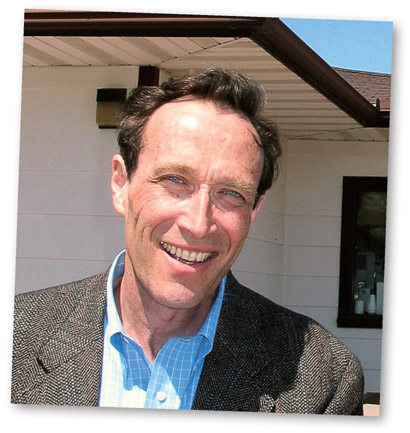

ABOUT THE AUTHORS

Jane and Michael Stern write books about travel, food, and popular culture. They are best known for their Roadfood books, website, and magazine columns, in which they seek out restaurants serving American regional specialties. They appear weekly on Lynne Rossetto Kaspers public radio program The Splendid Table, are contributing editors at Saveur magazine, and maintain the website Roadfood.com. They have won three James Beard Foundation Awards and the James Beard Perrier-Jouet Award for lifetime achievement. The Sterns books on American popular culture include Elvis World (1987) and The Encyclopedia of Bad Taste (1990). Their memoir, Two for the Road: Our Love Affair With American Food, was published in 2006. They live in Connecticut. Visit them at www.roadfood.com.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Our deepest thanks go to the restaurateurs, waiters and waitresses, cooks and chefs, pit-masters, pie bakers, pastrami slicers, chocolatiers, and chili wizards who uphold American culinary tradition. Without these people, and without the adventurous eaters eager to support and savor their efforts, America could be a land of nothing but soul-killing Happy (NOT) Meals.

Over a decade ago when Stephen Rushmore conceived Roadfood.com, we never imagined it would become such a lively community of food lovers and a source of endless inspiration for us as we continue to explore the American food landscape. We are grateful to Stephen, to Roadfood team members Bruce Bilmes and Sue Boyle, Chris Ayers and Amy Briesch, Tony Baldamenti, Marc Bruno, and of course Big Steve Rushmore, as well as to all the good-food tipsters, restaurant reviewers, trip reporters, eat-n-greet organizers, and opinionated foodies who make Roadfood.com a daily unfolding adventure.

One of the most enjoyable ways we communicate our cross-country food adventures is to report about them weekly on Public Radios The Splendid Table. There is nobody more delicious to chat with than host Lynne Rossetto Kasper; and thanks to Sally Swift and Jen and Jen, the conversation flows like soft butter on a hot biscuit.

Weve been writing long enough to say with assurance that book publishing has pretty much gone to hell in a hand basket. But there are some wonderful exceptions to its meanness; and we are fortunate enough to have worked with them as we created this lexicon. Our agent, Doe Coover, remains a steady hand who is always helpful, encouraging, and focused. Our editor, Mary Norris, and the folks at Globe Pequot Press demonstrate daily that creating a book still can be a process where intelligence, dignity, and kindness prevail.

AMERICAN CHOP SUEY

New England great-grandparents might remember American chop suey as school lunch or supper at home the day before payday. It is a frugal, homely, hopelessly nerdy dish, completely unlike the regions small repertoire of exotic fare, including fiddlehead ferns, glass eels, and cherrystone ceviche. It is too mundane to ever become trendy, especially considering its dubious genealogy as the penurious cooks knock-off of a discredited pseudo-Chinese dish.

We have seen a recipe in a 1930s cookbook that calls for it to be made with rice, which would explain its Asian moniker, but traditional ingredients are elbow macaroni, ground beef, and tomato sauce: generally, lots of sauce and noodles and just enough beef that the eater doesnt feel too deprived. It is more likely that the name was appropriated because it is a fanciful way to describe a dish of higgledy-piggledy, small-size ingredients. Unlike the dclass names of such similar mystery meals as slumgullion, cannibal stew, sloppy joe, and garbage plate, American chop suey adds a faintly exotic twist to its plebian ingredients.

It is so ignoble that even hidebound Yankee diners and small-town cafes specializing in cheap eats rarely put it on the menu anymore. But you can count on it every Monday at the Wayside Restaurant, between Barre and Montpelier, where it is listed as the Vermont Special.

Deluxe American Chop Suey

Now, theres an oxymoron for you. By its nature, American chop suey is not deluxe. It is spare and stingy. But several years ago, when we wrote our book Chili Nation, we augmented the basic formula with the likes of grated cheese and chow mein noodles and came up with a big bowl of comfortmaybe not quite deluxe, but presentable in polite company. True to the soul of the dish, it is no trouble to make and is easy on the pocketbook.

American chop suey is fusion cuisine: Italian sauce and elbow macaroni, a Chinese name, and Yankee ingenuity.

2 tablespoons cooking oil

cup diced onion

1 cup diced celery (about 2 ribs)

1 pound lean ground chuck

2 10-ounce cans Ro-Tel Diced Tomatoes and Green Chilies

1 teaspoon ground cumin

1 tablespoon chili powder

1 teaspoon salt

8 ounces elbow macaroni

1 cup grated sharp Cheddar cheese

Chow mein noodles, for garnish

1. Heat the oil in a heavy saucepan, and then saut the onion and celery until soft. Stir in the beef and cook until brown, breaking it up for a pebbly consistency. Add the Ro-Tel tomatoes and chilies, cumin, chili powder, and salt. Simmer vigorously for 15 minutes or so to reduce the liquid.

2. While the chili simmers, cook the elbow macaroni in boiling salted water until tooth-tender. Drain. Stir the noodles into the beef mixture.

3. Divide chop suey among four bowls and serve piping hot with grated cheese melting on top and chow mein noodles sprinkled atop the cheese.

4 SERVINGS

ANDOUILLE

A coarsely ground, highly spiced, and extremely smoked sausage made by butchers in French-accented Louisiana, andouille is a popular ingredient in gumbo and jambalaya. It is intense enough that it is frequently combined with blander elements: cheese grits or red beans and rice, for example. The Andouille Capital of the World is LaPlace, in St. John the Baptist Parish, just west of New Orleans. The official slogan of LaPlaces annual October andouille festival is A Smokin Good Time!

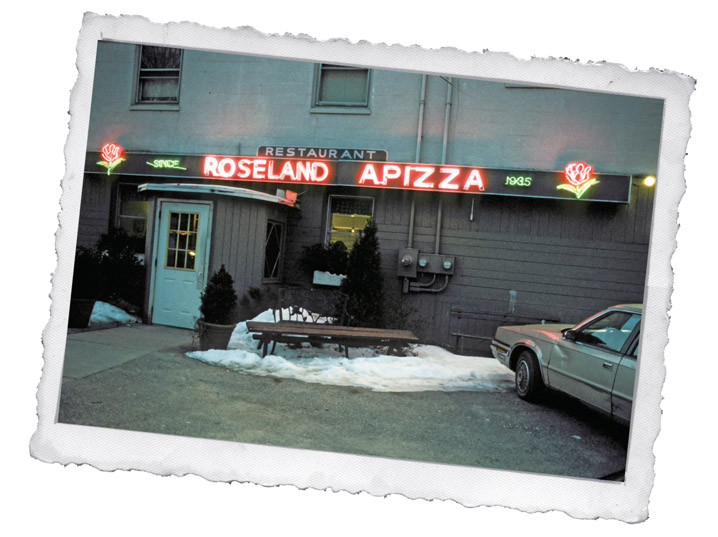

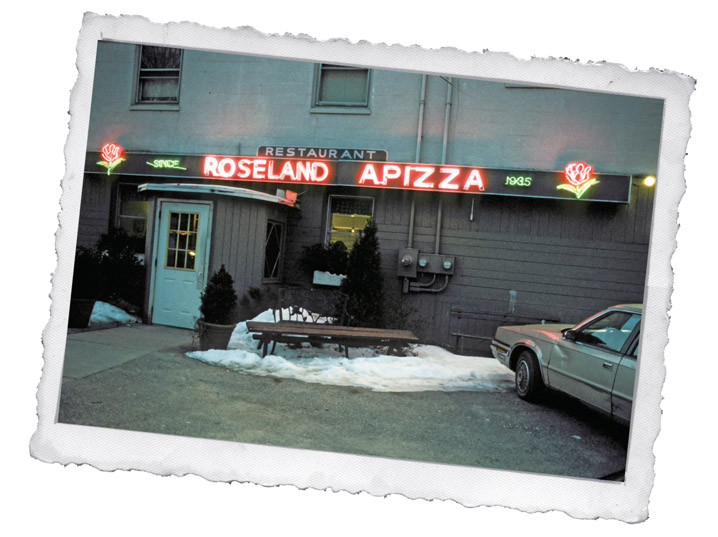

APIZZA

On the signs of pizza parlors throughout southern New England, you will see the word apizza where it seems like pizza is whats meant. Starting in the 1930s, when bakeries in Italian neighborhoods began to turn their attention to pizza, the a was added at the beginning of the word to give it a Neapolitan flavor when spoken. To pronounce it correctly, do not simply add an a to the start of the word pizza. The last a is always silent and the p is treated like a b. With a slow-rolling halt at the first syllable and a downward spike on the second, the word is properly pronounced uh-BEETZ. If you want to get an apizza the way virtually every Connecticut pizzeria made it in the early days, and the way purists still demand it, ask for a tomato-only pie, with perhaps a sprinkling of grated hard cheese. Those in the know call out, Uhbeetz, hold the mutz, mutz being shorthand for mozzarella cheese (known to pizzaiolipizza makers as cream cheese in American pizzas early days because of its consistency).