Sue Simkins works as a recipe developer and writes recipe columns for several monthly magazines including Best of British, Country Smallholding and the Countryman. Her recipes cover the whole range of wholesome home cooking with plenty of baking. They are the kind of recipes that novice and experienced cooks will all enjoy: simple and delicious with helpful tips and explanations. Sue lives in Dorset with her family.

Also by Sue Simkins

Cooking with Mrs Simkins

Cakes from the Tooth Fairy

Fresh Bread and Bakes from your Bread Machine

How to Make the Most of Your Food Processor

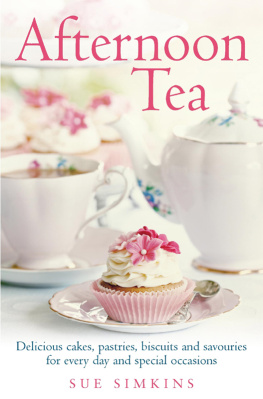

Afternoon Tea

Delicious cakes, pastries, biscuits and savouries for every day and special occasions

SUE SIMKINS

Constable & Robinson Ltd

5556 Russell Square

London WC1B 4HP

www.constablerobinson.com

First published in the UK by Spring Hill,

an imprint of How to Books, 2010

This edition published by Right Way,

an imprint of Constable & Robinson Ltd, 2014

Copyright Sue Simkins 2010, 2014

The right of Sue Simkins to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted by her in accordance with the Copyright, Designs & Patents Act 1988.

All rights reserved. This book is sold subject to the condition that it shall not, by way of trade or otherwise, be lent, re-sold, hired out or otherwise circulated in any form of binding or cover other than that in which it is published and without a similar condition including this condition being imposed on the subsequent purchaser.

A copy of the British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data

is available from the British Library

ISBN: 978-0-71602-370-8 (paperback)

ISBN: 978-0-71602-376-0 (ebook)

1 3 5 7 9 10 8 6 4 2

Printed and bound in the EU

Contents

Acknowledgements

I would like to thank my family and friends and everyone who helped with the making of this book.

Special thanks to Moira Blake of Dorset Pastry, Deidre Hills and all the members of the Marnhull Mothers Union, Adrian Curtis (Family Butcher), Clive Mellum of Shipton Mills, and to Claire Tuck, Daniel Parr and everyone at Clipper Teas who kindly supplied tea notes an .

As ever, thank you to Fanny Charles and everyone at the

Blackmore Vale Magazine.

And finally, a huge thank you to everyone at Constable & Robinson.

Thank you all very much indeed.

Introduction

Helpful Equipment

Here are the most useful sizes of baking tins, most of which are used in this book. Heavier, better quality baking tins conduct heat more efficiently than anything thin and flimsy. They also have a longer life.

Large baking tray

A baking tray that just fits comfortably inside your oven can be used for all kinds of bread and biscuits and scones.

Standard 20cm (8in) square brownie tin

This is a really useful size and shape for brownies and small tray bakes.

12-cup muffin tin

As well as muffins this is perfect for buns, rolls, fairy cakes and deep-filled tarts.

12-cup mini-muffin tin

A couple of these are useful for tiny cakes and tarts.

12-cup tart tins

Its useful to have a couple of these for tarts, mince pies and small quiches.

Loose-bottomed cake, sandwich and flan tins

Its handy to have the following sizes:

18cm (7in) cake tin; pair of 18cm (7in) sandwich tins; 20cm (8in) cake tin; 20cm (8in) flan tin; 23cm (9in) cake tin particularly if you make your own Christmas cake.

Loose-bottomed 10cm (4in) tartlet tins

Often sold in packs of six, these are perfect for elegant individual fruit tarts and also for individual quiches and savoury flans.

Mini loaf tins

Often sold in packs of four, these are brilliant for sweet, dinky, little loaves of bread and bar cakes. Its useful to have 12, but theyre not cheap so its worth knowing they hold the same amount of mix as the cup of a 12-cup muffin tin enabling you to make a mixed batch.

Look after them carefully to keep them in good condition: instead of scrubbing them in hot soapy water or throwing them in the dishwasher, its usually possible to clean them perfectly well by wiping with kitchen paper.

Ceramic baking beans

Treat yourself to some proper ceramic baking beans: two tubs would be ideal. Ceramic baking beans conduct the heat more efficiently than dried peas or beans when baking pastry flan cases blind. They help to conduct heat to the inside of the pastry case as well as weighing it down and supporting the sides.

Oven Temperature Conversions

Mark 1 | 275F | 140C |

Mark 2 | 300F | 160C |

Mark 3 | 332F | 170C |

Mark 4 | 350F | 180C |

Mark 5 | 375F | 200C |

Mark 6 | 400F | 220C |

Mark 7 | 425F | 230C |

Mark 8 | 450F | 230C |

Please be aware that individual oven performance varies greatly. |

Measurements

Both metric and imperial measurements are given for the recipes. Follow one set of measurements, not a mixture of both, as they are not interchangeable.

1. All Kinds of Tea Time Occasions

Afternoon Tea had very aristocratic beginnings. Although tea drinking started in Britain in the 17th century, sitting around, drinking tea with cakes and delicate little savouries came later.

By the 19th century, among the upper classes, lunch was served at midday and, for various reasons, dinner had become a very late meal: 8 oclock at the earliest, with nothing in between. Ladies were obliged to order a pot of tea during the afternoon along with a little something to keep them going. Eventually, friends and family were invited and the concept of Afternoon Tea began. And so it became a convivial opportunity for the ladies of the house and their friends to relax together and chat, as well as to stop their blood sugar levels from plummeting!

A kettle would be boiled on a small spirit stove near the tea table and the lady of the house would make the tea in a silver or bone china teapot. The food would be very delicate and refined: thinly cut bread and butter, cucumber sandwiches made with the slenderest slivers of peeled cucumber, dainty cakes on a pretty cake stand, and possibly something toasted in a covered silver dish served during the cold days of winter.

High Tea, on the other hand, came about out of necessity, once the Industrial Revolution had turned the majority of working people away from their home-based jobs and into the factories and mills. It was a substantial meal for the whole family at the end of a hard working day, as hearty as funds would permit, and brought to the table with the minimum of effort and accompanied by cups of strong tea.

Most of the family members would very likely have been working all day and would arrive home tired and hungry with little energy or inclination, or even a hot stove or fire, to cook.

During the 19th century tea had come down in price and was first drunk by the working classes as a precious treat, but as prices fell even more it turned into a household staple and was drunk at every mealtime, and often in between as well.

Next page