Dedication

To my mother Shirley Fenn

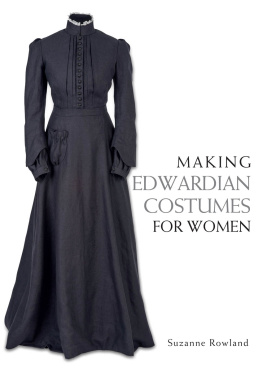

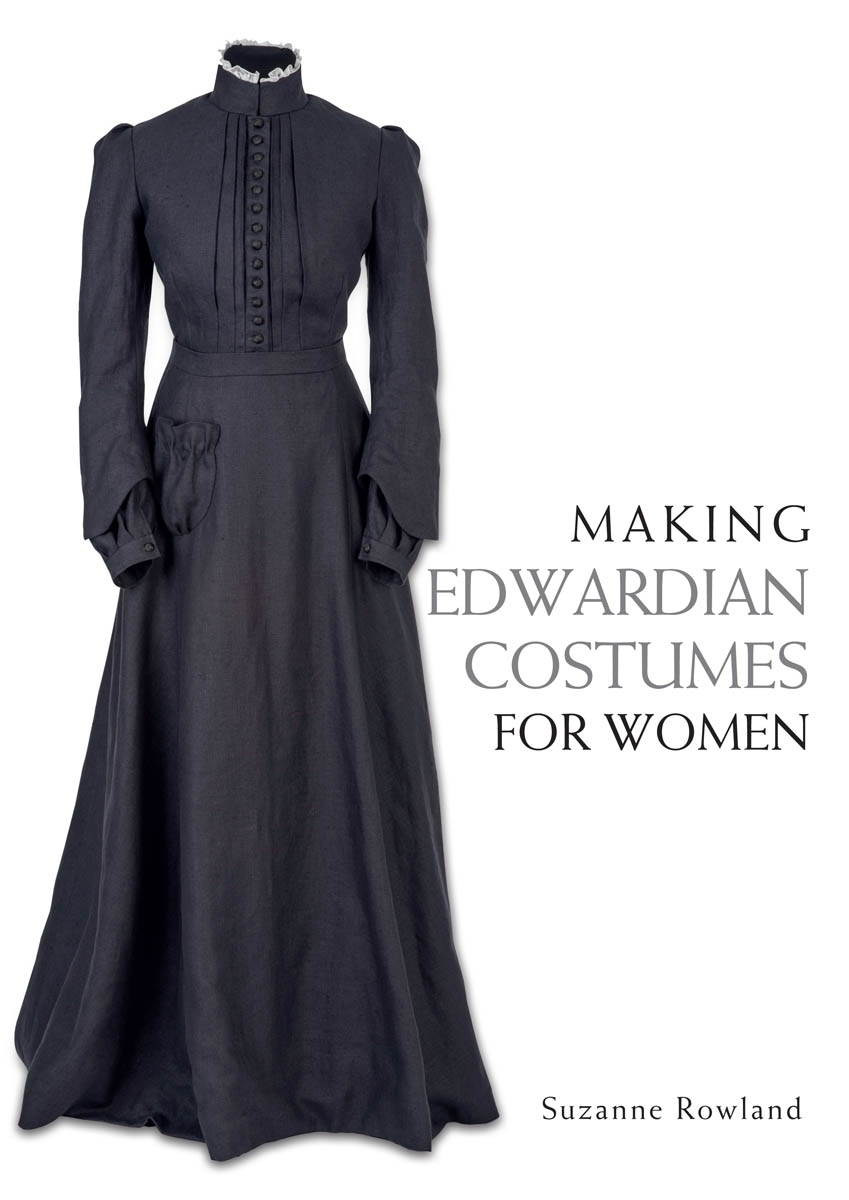

MAKING

EDWARDIAN

COSTUMES

FOR WOMEN

Suzanne Rowland

THE CROWOOD PRESS

First published in 2016 by

The Crowood Press Ltd

Ramsbury, Marlborough

Wiltshire SN8 2HR

www.crowood.com

This e-book first published in 2016

Suzanne Rowland 2016

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopy, recording, or any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publishers.

British Library Cataloguing-in-Publication Data

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

ISBN 978 1 84797 103 1

Photographs by Benjamin Rowland

Illustrations by Joe McRae

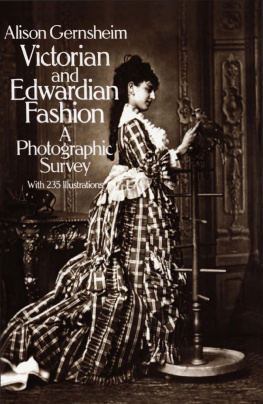

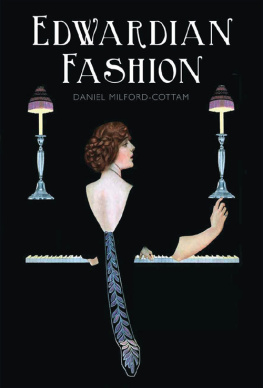

Frontispiece: Evening gown by Ida Pritchard. (Worthing Museum and Art Gallery)

Contents

Introduction

The selection of garments and accessories featured in this book are indicative of the kinds of projects made by an Edwardian dressmaker; this could have been a professional seamstress working from her own premises (it was a womans profession), a ladys maid or a skilled hand batch-producing blouses by the dozen in a small workshop. Tailored outerwear and corsets have not been included because these were specialist areas outside of the dressmakers realm of experience. The garments and accessories featured are either from the collection at Royal Pavilion & Museums, Brighton & Hove, or Worthing Museum and Art Gallery, which gives readers the opportunity to make appointments with either museum to view the original pieces. Using museum collections poses some limitations for the researcher; it is widely acknowledged that historical clothing most often worn is likely to have been discarded; clothing saved for best is generally what survives and therefore makes up the bulk of museum collections. Fortunately both museums have diverse collections. Worthing Museum is a treasure trove of handmade and department store clothing. Due to the foresight of curators the collection contains unique pieces of everyday fashion; some in stages of disrepair, some perfectly preserved. The Royal Pavilion & Museums fashion and dress collection also holds examples of clothing from department stores from mid-range to high end. It contains a number of sub-collections, including the clothing of wealthy women such as Katherine Farebrother, Lady Desborough and the Messel family, who were dressed by the top London couture houses and professional dressmakers. Due to a longstanding association with both museums (as a volunteer at Brighton and as a museum educator at Worthing) I have been fortunate in developing a familiarity with the collections and I have benefited from having generous access to the collections for research.

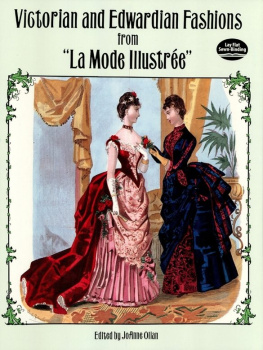

Two fashionable evening gowns in pastel shades sketched by fashion illustrator Ida Pritchard. (Worthing Museum and Art Gallery)

The criteria I used in selecting museum garments were as follows: firstly, all projects had to be suitable for reproduction; secondly, all fabrics and trimmings could be sourced without too much difficulty. A further objective was that projects should be adaptable and so projects have suggestions on how to adapt garments to make them suitable for both wealthy, leisured women, and for poorer women whose choices were limited due to a low income.

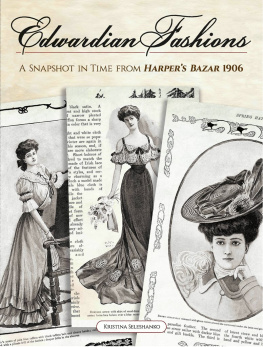

The Edwardian era, if characterized by the reign of Edward VII, stretches neatly from the beginning to the end of the first decade of the twentieth century (19011910). The sartorial influence of Edward and Alexandra, who married in 1863, extends beyond these boundaries, and therefore this book will cover a wider period stretching from the mid-1890s up to the mid-1910s. During the Edwardian period British society was rigidly divided by class, but by the end of the period things were changing due to new developments in the workplace and in industry.

Three dresses included in the book span the Edwardian era: a two-part walking dress with fitted bodice and trailing skirt from the turn of the century, a lightweight cotton day dress with pouched bodice and full sleeves from the middle of the era and a later style Empire line evening gown with beaded tulle panels.

Not all garments in the collections are dated and others have approximate dates only. A close look at the tools and techniques used in garment construction can help with dating. Garments made before the First World War often used metal hooks and eyes as closures on collars and plackets. Wartime restrictions on the use of metal made it difficult for the companies producing hooks and eyes to keep up with demand and led to a limitation of stock and an increase in prices. An advertisement in the garment manufacturing trade journal The Drapers Record, 14 August 1914, by the firm Newey Bros Ltd, shows that the firm were reluctantly increasing the price of hooks and eyes due to a great advance in the price of metal.

Researching projects began in the museums archives with the clothes and accessories and developed to include a range of additional sources. Worthing Museum has a wide selection of Edwardian dressmaking manuals and journal features in the archives, which include Isobels Dressmaking at Home, Weldons Illustrated Dressmaker and Weldons Home Dressmaker. They also have a boxed set of dressmaking booklets dating from 1914 to the early 1930s produced as a correspondence course by the Womans Institute of Domestic Arts & Sciences, which was based in Scranton, Pennsylvania. The course offered a range of valuable instructions for dressmakers, from how to stock and manage a workroom to how to become more proficient in the skilful use of a needle and thread when embroidering monograms on lingerie. The Drapers Record archive held at The London College of Fashion has been a useful source of research; further sources have included womens journals, Government Reports, social surveys, dressmaking manuals, costume reference books and museum visits. I was particularly inspired by Janet Arnolds comprehensive observations of museum dress captured in detailed sketches in Patterns of Fashion 2 (1982). Anne Bucks careful study of garments and accessories made when she was Keeper of the Gallery of English Costume at Platt Hall, Victorian Costume (1961), was a further source of inspiration, as was Lou Taylors exploration of the development of dress through object-focused research in The Study of Dress History (2002).

Chapter 1 Edwardian Fashion and Dressmaking | |

FASHION FOR ALL

The defining shape of the Edwardian period is the S-shaped silhouette, which refers to the shape of a woman in profile. The flat-fronted corset, seen in advertisements from 1900 to 1908, provided the first layer of shaping to the body, although it did not shape in the extreme way suggested by corset advertisements. The Erect Form corset was featured in The Drapers Record in 1902 and showed an exaggerated version of the fashionable shape with a tiny waist, large bosom and protruding rear end. Much of the exaggerated shaping of the S-shaped silhouette was achieved by the outer layers of clothing, which included pouched front blouses and skirts that were flat at the front, smooth over the hips, with soft pleats or gathers at the centre back sitting on top of a similarly shaped petticoat. High fitted collars, trailing skirts and large hats, all decorated with flounces and embellishments, completed the look. Edwardian fashion was not always practical, or indeed comfortable. The straight fronted corset had the effect of flattening the stomach and encouraging the lower back to arch. The trailing skirts could also be a hindrance, as recalled by the Prime Ministers daughter-in-law, Lady Cynthia Asquith, in her memoir Remember and Be Glad: