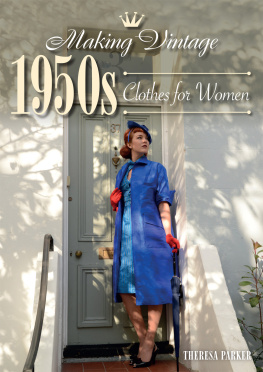

Making Vintage

1950s

Clothes for Women

Making Vintage

1950s

Clothes for Women

THERESA PARKER

THE CROWOOD PRESS

First published in 2018 by

The Crowood Press Ltd

Ramsbury, Marlborough

Wiltshire SN8 2HR

www.crowood.com

This e-book first published in 2018

Theresa Parker 2018

All rights reserved. This e-book is copyright material and must not be copied, reproduced, transferred, distributed, leased, licensed or publicly performed or used in any way except as specifically permitted in writing by the publishers, as allowed under the terms and conditions under which it was purchased or as strictly permitted by applicable copyright law. Any unauthorised distribution or use of thistext may be a direct infringement of the authors and publishers rights, and those responsible may be liable in law accordingly.

British Library Cataloguing-in-Publication Data

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

ISBN 978 1 78500 436 0

Contents

Introduction

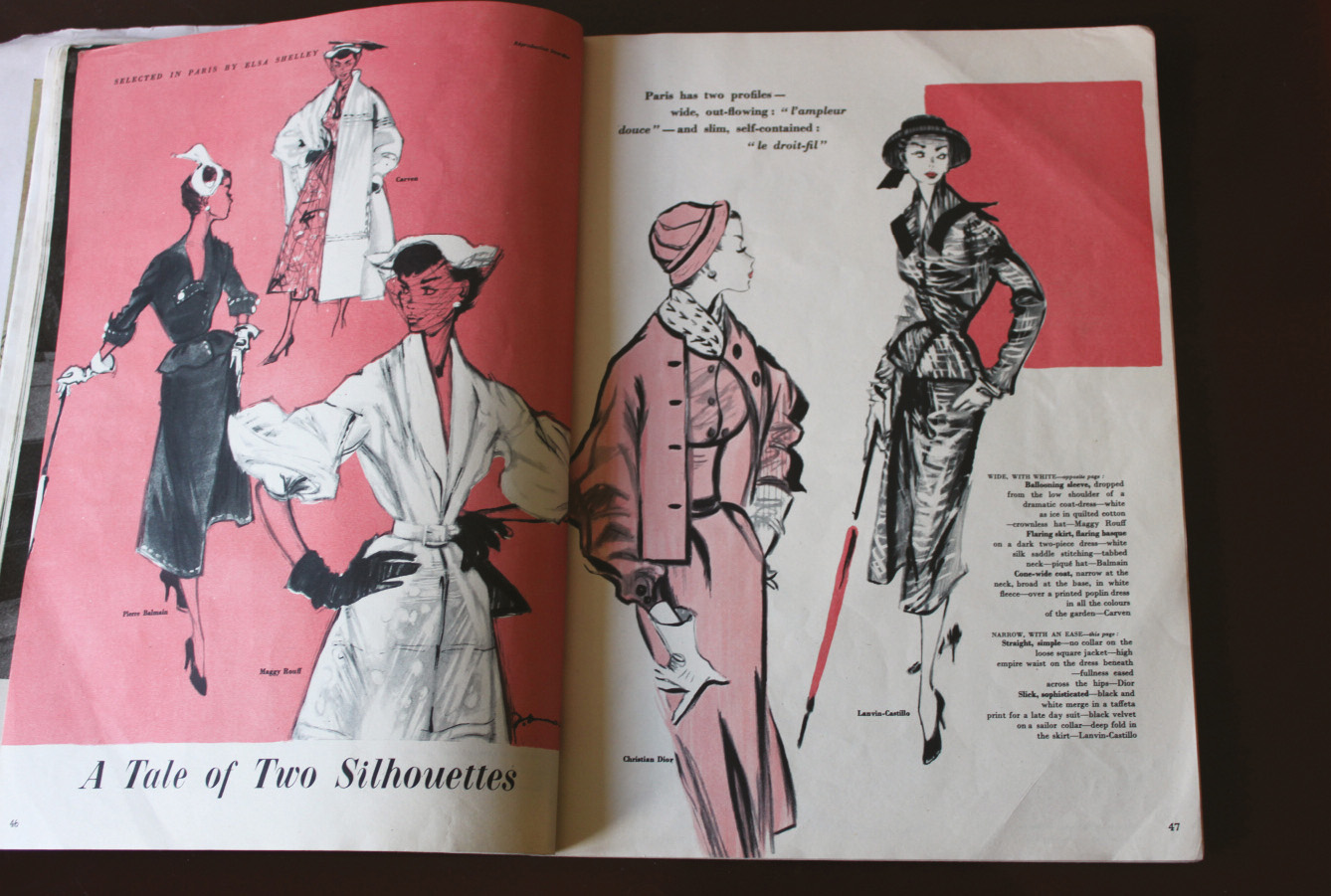

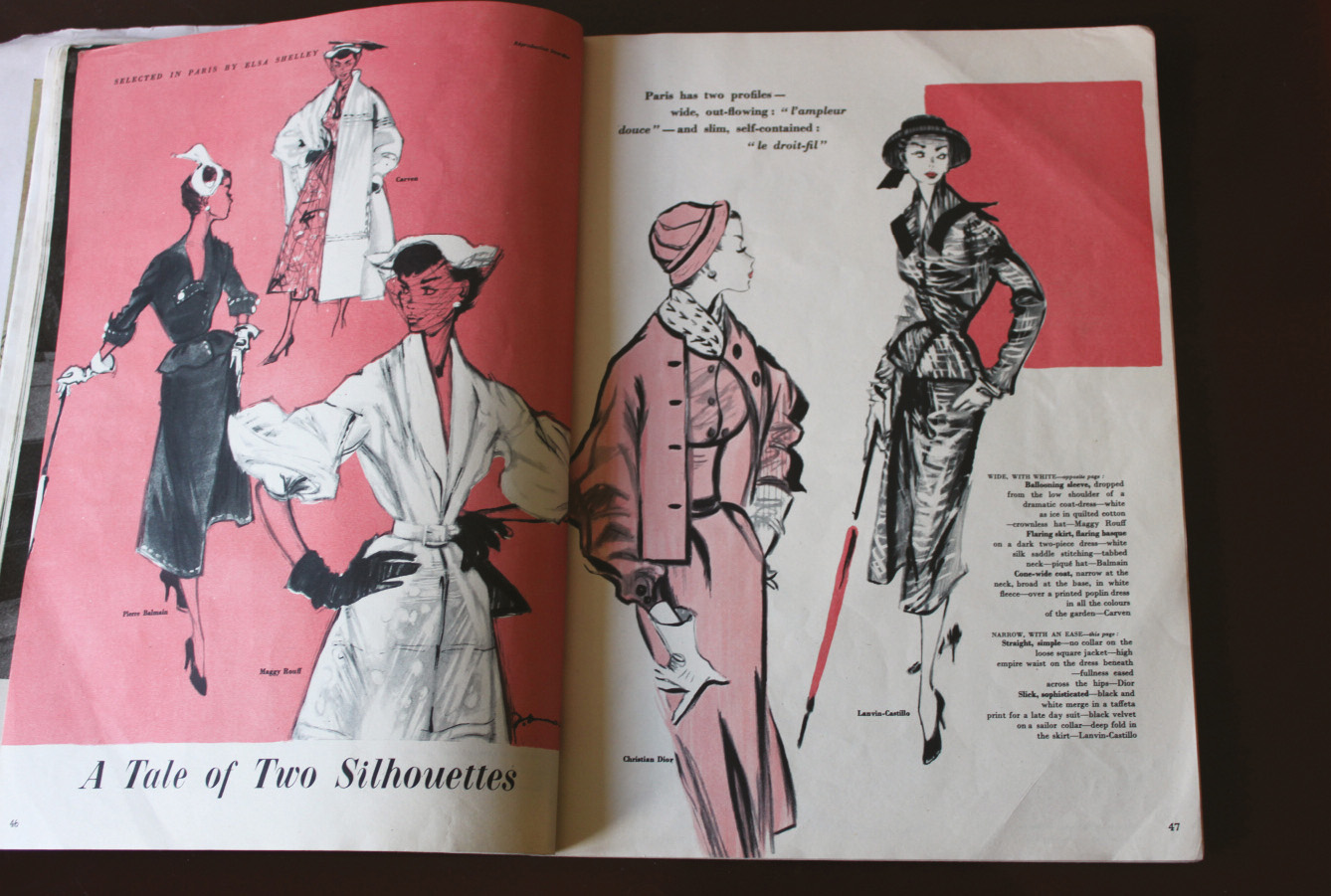

Paris has two profiles wide, out-flowing: lampleur douce and slim, self-contained: le droit-fil.

UK Womans Journal, February 1952

In this book I have tried to identify what I think are the key silhouettes for the decade. I have applied the same research process as I would employ when designing a wardrobe for a character in a film or creating a fashion collection. The inspiration for the projects has come from a variety of different sources with some elements that are completely true to the originals and some that have required a degree of interpretation to figure out. This is normal when all the information needed cannot come from one source alone. For example I have frequently referred to my own collection of vintage magazines, especially the British and American editions of Vogue and Womans Journal, to identify the fit of key looks for the period, even though I could not always see the construction processes in the photographs. I have also used museum archives to examine garments at first hand for a more tactile investigation into construction and fabrication but as they are of historical interest and need to be conserved I could not try them on to see the fit. I have also referred to a variety of original 1950s paper patterns, which did not always come with markings or instructions, and so half toiles frequently had to be made to identify fit or order of manufacture stages (toile is the French term for a test garment and a half toile is literally one half, or slice, of that garment). I also frequently had my nose in vintage instruction manuals for pattern drafting, construction and finishing techniques, which I also tested in calico before committing anything to the real fabrics.

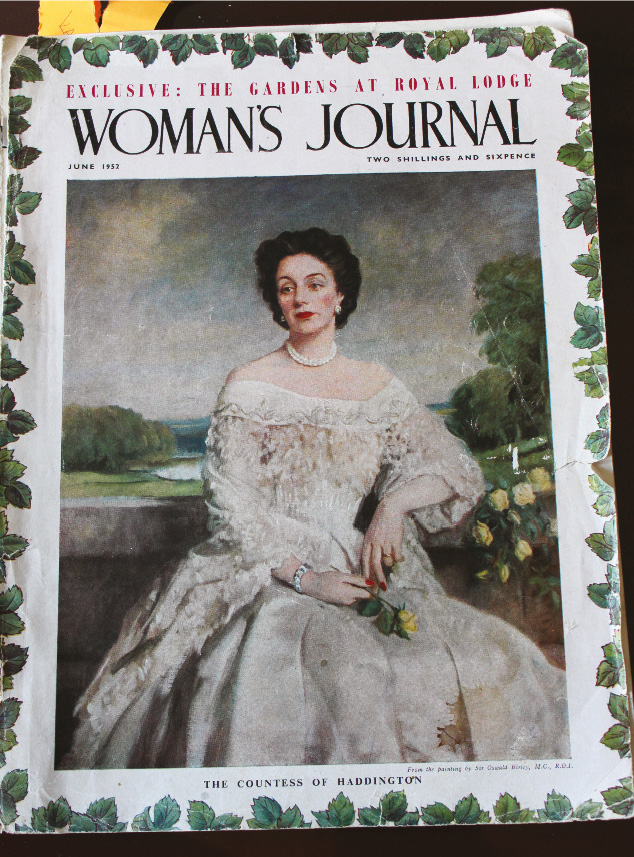

Two silhouettes from UK Womans Journal, June 1952. (Authors own collection)

I have been inspired by the ingenuity of garments made by both couturiers and home dressmakers. The quality of manufacture is incredibly varied and obviously down to the skill and competency of the seamstress and her experience with the equipment at her disposal. For some women that was only a needle and thread, whilst others would have used hand sewing machines or treadle versions and some had treadle machines converted into electric models.

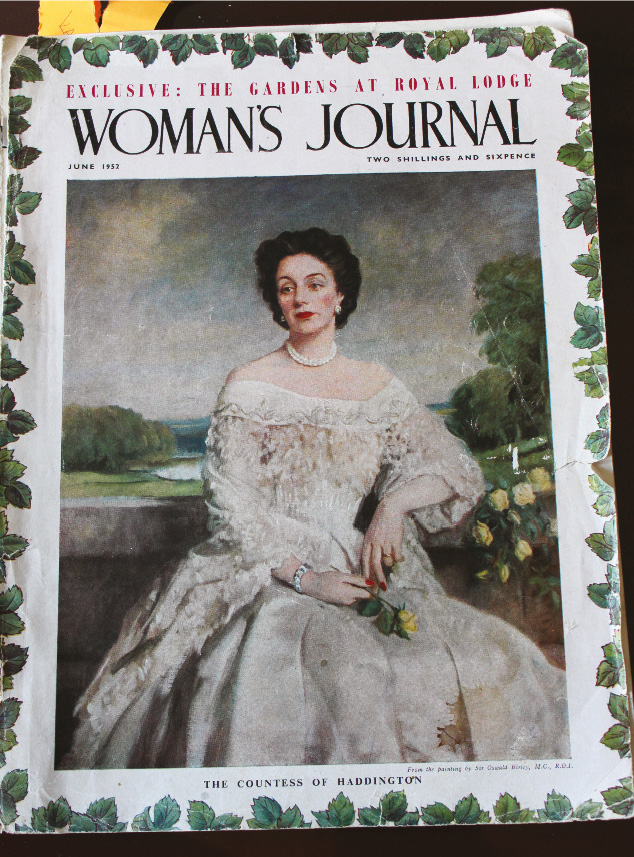

Cover of UK Womans Journal showing a painting of the Duchess of Haddington in a Dior gown, June 1952. (Authors own collection)

Behind the scenes at the Worthing Museum and Art Gallery.

Vintage pattern. (Authors own collection)

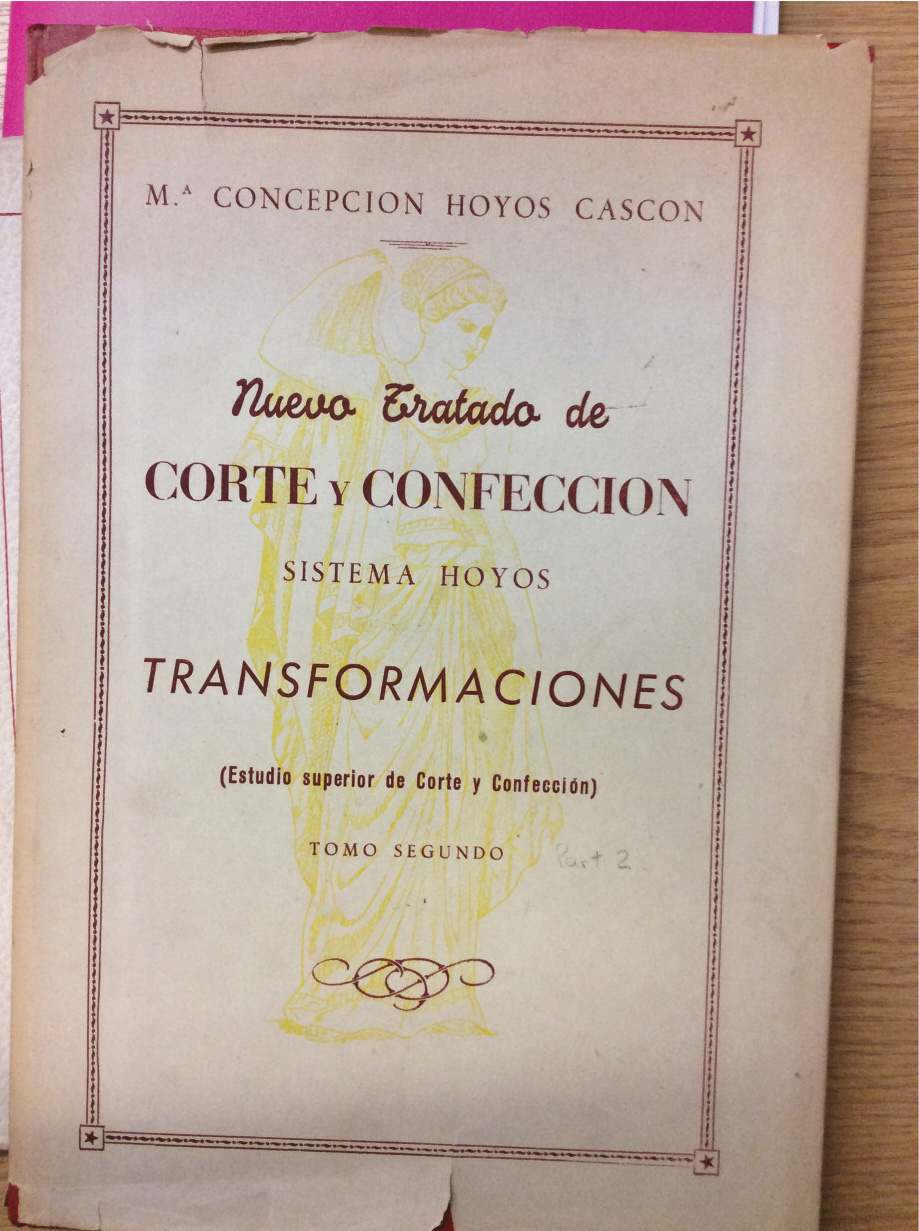

Pattern manual. (Worthing Museum and Art Gallery)

Instruction manual. (Authors own collection)

I had extensive access to the archives at Worthing Museum and Art Gallery, which has influenced the projects selected for the book. The focus of the archive is specifically on maker/owner pieces, catalogue buys and garments made by local tailors and less about pieces made by well-known designers of the time. That is not to say that the latters aesthetic did not influence what women chose to make or buy as the garments effectively fell into two key silhouettes already identified in Vogue as the Paris profiles most of us already associated with clothing of that era. The looks have clearly been inspired by the work of couturiers as have the frequently sophisticated quality of finishing; for example, many of the garments are fully lined and turned through at the shoulders. This construction method enables raw seams to be covered and encompasses a neat way of completing tiny shoulder straps. Archive pieces from the late fifties have sometimes incorporated a zigzag stitch, no doubt speeding up the neatening processes and allowing women to machine their own buttonholes for the first time. It has also been interesting to see examples of pinking employed both by the home dressmaker and couturiers.

House of Youth/Dior kimono jacket lining. (Worthing Museum and Art Gallery collection)

House of Youth dress with pinked finish on seam. (Worthing Museum and Art Gallery collection)

The New Look

The overriding silhouettes of the decade originated in Paris with the couture house of Christian Dior being particularly influential. Dior constructed his dresses based on his observations of the female body and the desire to idealize its proportions. The names he chose for his lines reflected the dominant silhouette from each show, such as the Corolla, the Zigzag, the Oblique and the Sinueuse, to name but a few. The lines were described in great detail in press kits, providing journalists with a commentary on the latest fashion innovations.

The name of Diors first collection for his own fashion house was La Ligne Corolle. Dior was very much inspired by nature and the name was actually a botanical term referring to a circlet of flower petals, a concept he endeavoured to capture with his designs. Carmel Snow, editor-in-chief of

Next page