Acknowledgments

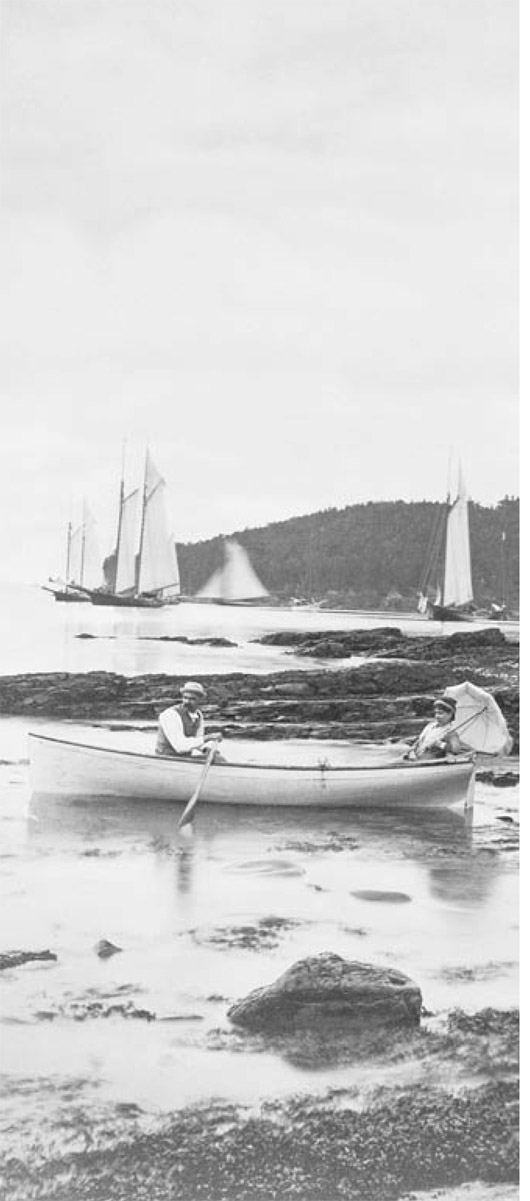

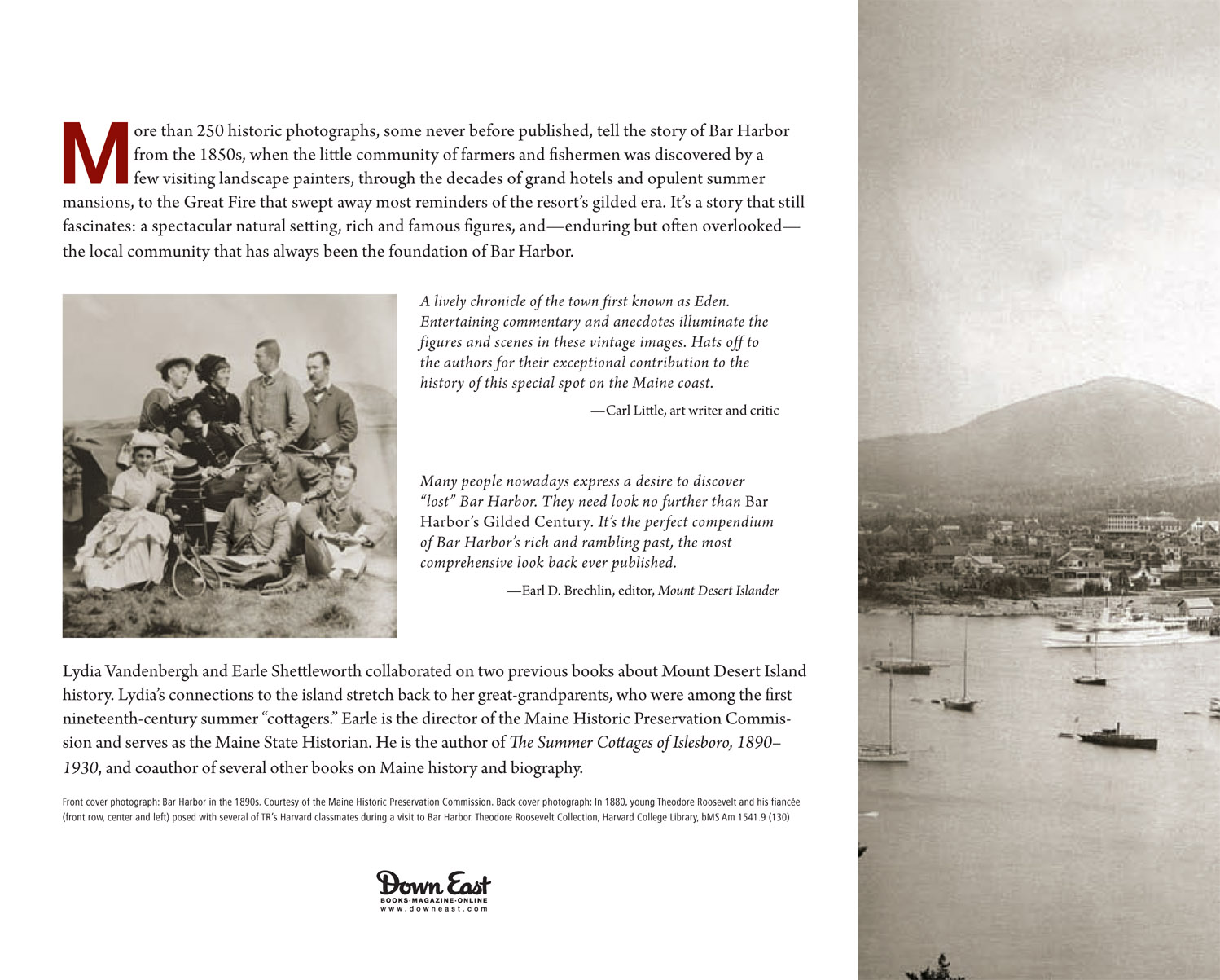

Without the help of many people, this book would not have contained as many photographs and interesting details for readers to enjoy. Earle G. Shettleworth Jr., the director of the Maine Historic Preservation Commission (MHPC), spent countless hours poring over more than 1,000 photographs to select and position the 255 that would tell the story of Bar Harbors century, and he also edited each caption. Sargent M. Collier not only helped with the research and tracking down details, but he also contributed the captions for eight images (the top photo on pages 166 and 168, bottom photo on pages 152 and 160, and both photos on pages 167 and 170). Several of the 1940s photographs were taken by his grandfather, Sargent F. Collins. Debbie Dyer, the energetic and knowledgeable director of the Bar Harbor Historical Society, provided generous assistance in locating photographs from that organizations invaluable collection. For help with the caption about the racing yachts photo on page 169, we turned to Sturgis Haskins, who contributed his elegant writing style.

We are indebted to Christine Norris and Elizabeth Trautman of the MHPC staff for their support of this project. We called upon a few experts to write all or parts of specific captions, including Sturgis Haskins, Arlene Palmer Schwind, and Elizabeth Igleheart. Others contributed information for the captions, including Claire Lambert, Florence Ames, Nancy Howland, Library of Congress archivist Kevin Lavine, Alexander Phillips, Craig Colwell, John Clark, Bill Bunting, Ruth Soper, John McDade of Acadia National Park, Bunny McBride, Jeff Curtis, Jim McLeod, Mrs. Stockton Andrews, John Wall, Leslie Brewer, James Blanchard, Alison Salsbury, Steve Raab, and Charles Campos.

David Mishkin of Portlands Just Black & White photo lab worked his magic improving some of the old photographs. It was always a pleasure to visit with Raymond Stout, who gave generously of his time and willingly shared his photo collection with us. When I needed help on genealogical questions, Sheldon Goldthwait thoroughly answered them, and enjoyed a bit of sleuthing along the way. I appreciate the time that Elizabeth Gorer, John Goldthwait, James Blanchard, Corinne Graham, Dorothy Fillettaz, and Lois Frazier took to tell me and Sargent M. Collier about the old days. Many thanks to Boo and Dave Butler for their hospitality. I am indebted to several institutions for their collections, including Penn State University Libraries, the University of Maine at Orono, the Jackson Laboratory, and the Abbe Museum.

Our Down East Books editor, Karin Womer, not only provided guidance for this project, but also proved to have an abundance of patience.

Lastly, this book was truly a family effort, with content and editorial support provided by my husband, David Vandenbergh, and children, Christina and Alex.

BY THE 1890s, BAR HARBOR cottages had grown in scale and formality. Mrs. Hardy had expanded Birch Point with extensions to the side and rear, as well as a wraparound porch. By this time, most cottagers were no longer taking their meals at nearby hotels. Instead, they had enlarged their summer homes with functional kitchens and larger dining rooms to better entertain their guests.

More than half a century later, the Bar Harbor Motor Inn (now the Bar Harbor Inn) would be built on this spot, affording its guests the same pleasurable view the Hardys had so enjoyed from their veranda.

Photo courtesy of the Maine Historic Preservation Commission

BY 1870, BANGOR RESIDENT Alfred Veazie, a Harvard-educated lawyer, had amassed a fortune, having worked his way up from cashier to president in his grandfathers local bank. Veazie and his wife, Etta (ne Hodsdon), bought land from Tobias Roberts and hired Bostons prestigious Doane contracting firm to build their cottage just west of the Hardy place on the shore. The Veazie cottage, now called The Kedge, reflected the postCivil War preference for the French mansard-style roof, with its distinctive dormered roofline and a picturesque cupola.

After Veazies death in 1879, the cottage became the home for the Oasis Club, a gentlemens social group. The house was later moved to West Street and converted back to a summer cottage, which it remains today.

Photo courtesy of the Maine Historic Preservation Commission

The Island Settlers

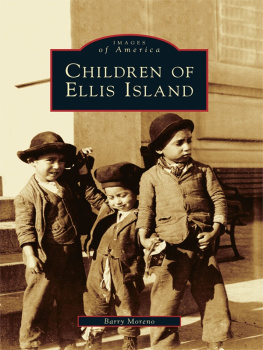

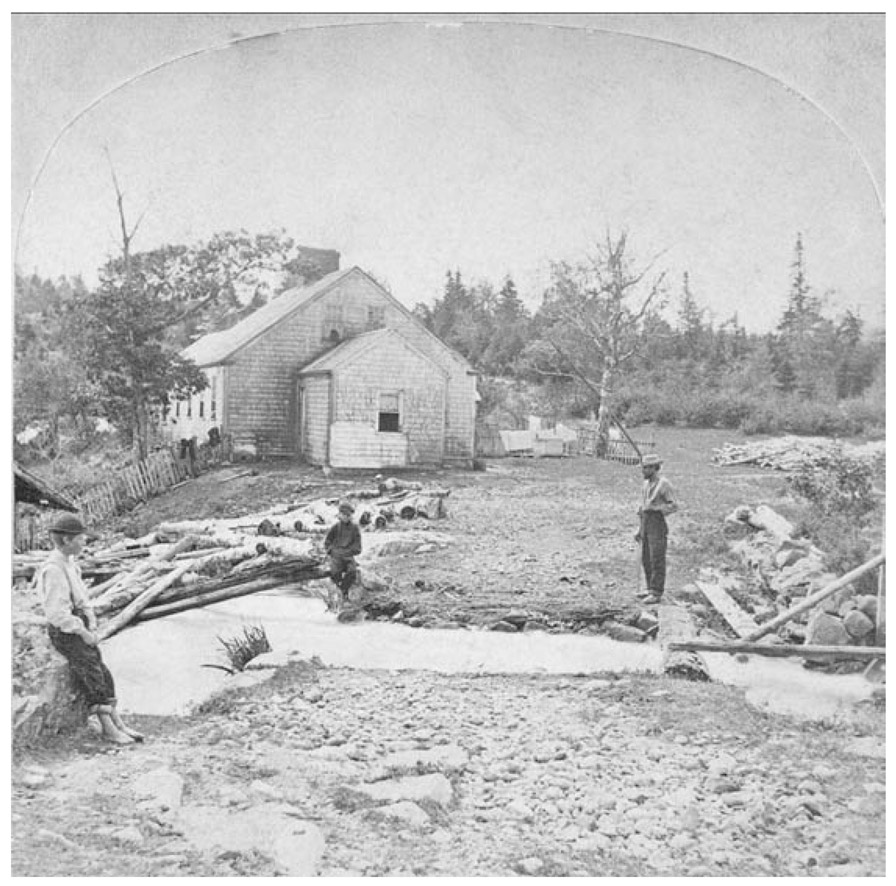

LIKE THE SUMMER SOJOURNERS who would follow in later years, William Lynam was attracted to Mount Desert Island for its abundant resources and beauty. The island offered plenty for making a living in nineteenth-century Maine: lumber for building ships, houses, boxes, and furniture; water to power the mills and navigate to other ports for trade; fertile soil to grow food; and fish for eating and selling. A blacksmith by trade, Lynam moved with his wife, Hannah Tracey, from Gouldsboro, Maine, to the island in 1831 and built this modest homestead at Schooner Head. Over time, this homestead would be described as lonely and not specially picturesque by famous artists who boarded there, but who nevertheless made it their temporary home during their sojourns on the island.

Photo courtesy of the Maine Historic Preservation Commission

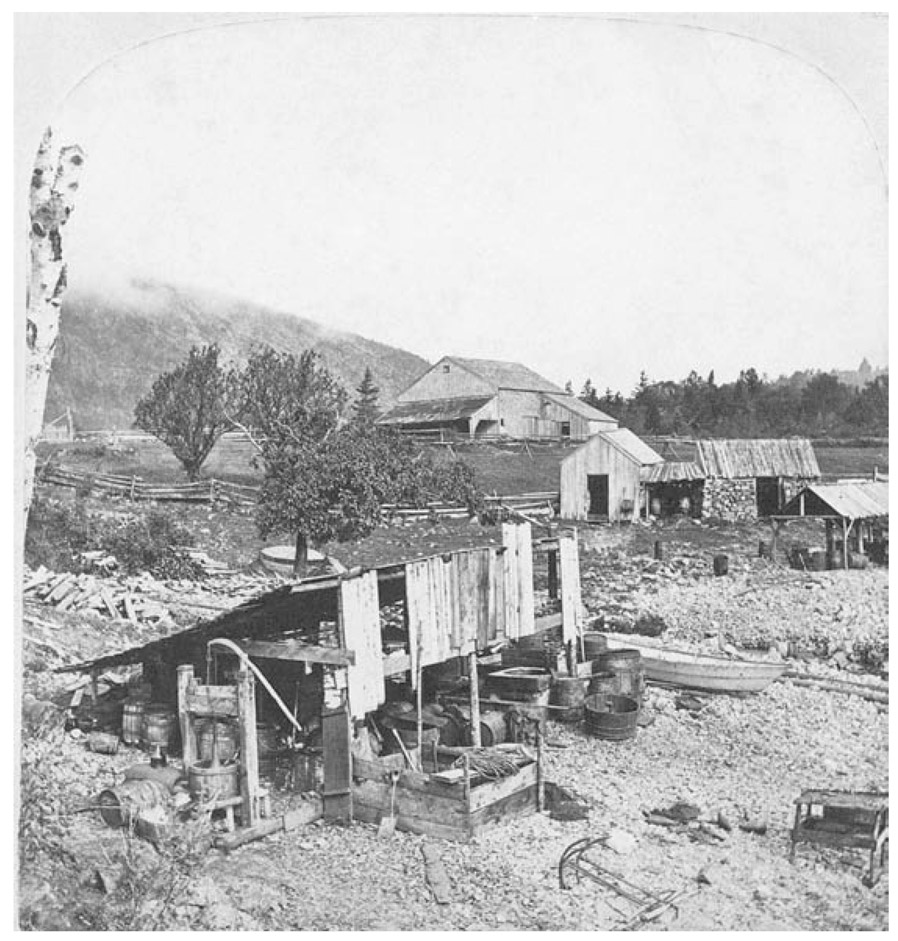

LYNAM WAS a subsistence farmer like many of his fellow islanders, producing enough pork, lamb, dairy products, and vegetables to feed his wife and nine children. During the Civil War, islanders set up oil presses such as this one in which menhadenalso called pogieswere boiled and pressed to produce oil. For a few short years, the oil sold for $1.25 a gallon, five times its prewar price, before overfishing depleted the resource in this area. Women assisted in the process by knitting (netting) pogy nets, sometimes making thousands of knots over the course of many days to create a two-inch-mesh net, two hundred to five hundred feet long by eighteen feet deep.

Photo courtesy of the Maine Historic Preservation Commission

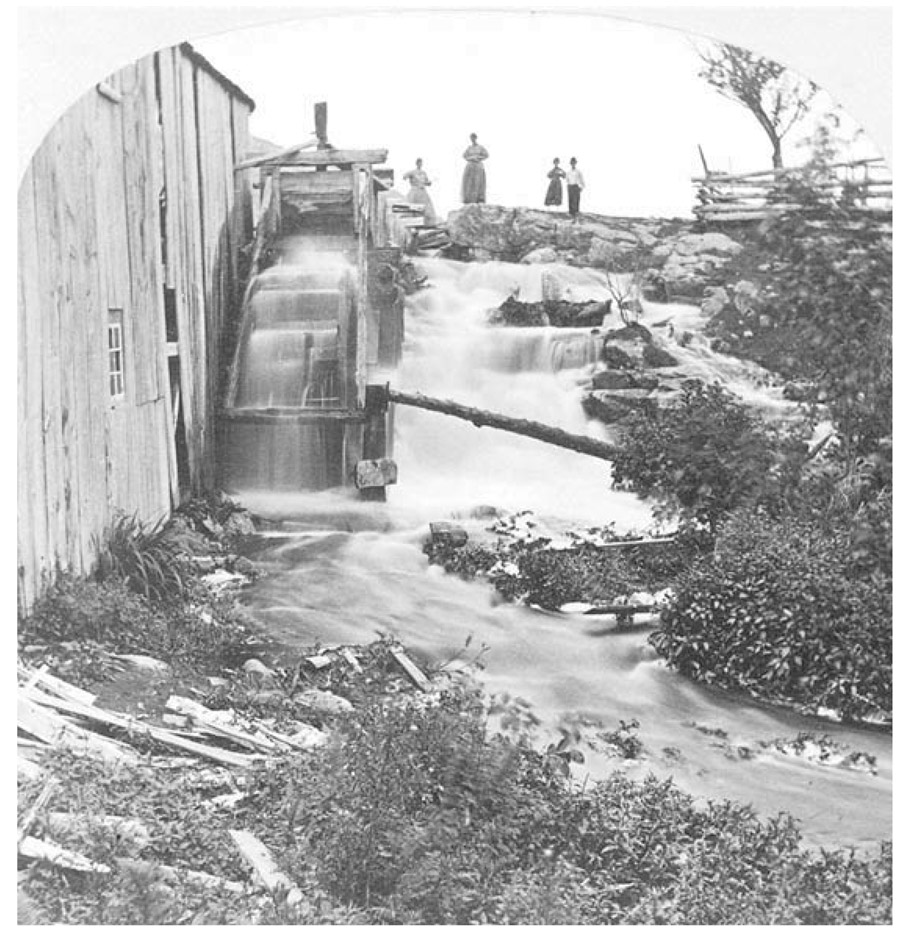

THIS WATER WHEEL was an important source of power in the nineteenth century. Lynam would cut down trees in early spring and haul them back to his water-powered sawmill with a team of oxen. He cut the wood into lumber, shingles, spool blocks (for vessels), and other products to sell in local and national markets. Besides the homestead and mill, Lynams hundred-acre farm at Schooner Head included two oxen, two cows, a young horse, and twelve sheep.

According to common lore, sailors called the area Schooner Head because they said that in the fog, the pale stone of the headland resembled the white sails of a schooner.

Photo courtesy of the Maine Historic Preservation Commission