This book made available by the Internet Archive.

To my wife, Joyce, may she always remember our good days.

And to my son, Francesco, who made every day worth remembering.

And in memory of Connie and Carl who made me, and left too soon.

Thanks for the time of my life.

v;..

Acknowledgments

v;.-.

MANY FRIENDS HELPED WITH THS PROJECT, aS they have in the past, and again I owe them much.

Joyce and Francesco spent many patient hours Hstening to me tell stories and share frustrations, and they helped guide me in this endeavor. Their story is hidden in the corners of almost every page of this book. Without their patience, help, and love this book could not have been written.

Tammy Boggs, Rick Tagg, Dottie Jacobsen, and Tina Zaras, wonderful friends, watched my battle and helped me in many varied ways, some unknown to them. Rob Lively, a friend of longstanding, lent more than moral support.

My sister, Mary Ann Lovett, opened her heart and helped me remember her role in my growing up, while my cousins Suzanne and John Cain called regularly from the West Coast to remind me of events when we were together in Eldora, and to cheer me. My longtime friend Rob Hurwitt made suggestions on the finished manuscript and helped reduce typos.

Pete Dawson, our family's ribald historian, traced evidence of Alzheimer's in the DeBiaggio family and provided levity. His family chronicle of the Dapalonia and DeBiaggio families provided some useful background that was outside my memory.

My good friends Susan Belsinger in Maryland and Carolyn Dille in California kept my spirits high with frequent telephone calls.

Vll

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Linda Ligon of Interweave Press, a friend of many years, encouraged my writing over the years, often in the best way, with money for work pubUshed in her magazines and books, and she prodded me to keep going during these tough times.

Noah Adams was helpful in many ways.

I am indebted to Dr. Colleen Blanchfield, a neurologist with a large heart for her patients and a sensitivity for their humanity. She is an honor to her profession.

I am particularly indebted to Jonathan Lazear and Christi Cardenas for their help and their enthusiasm for my writing.

My profound thanks to those men and women, and mice, around the world who work to understand Alzheimer's and bring its awful nightmares to an end.

Vlll

Author's Note

v;^.

THIS IS A BOOK BALANCED BETWEEN thewondcrof child-hood and the tottering age of memory. I used an unconventional multilayered style in this book to illustrate memory's many faults and strengths. It is an attempt to show the parameters of long-and short-term memory and how Alzheimer's works to destroy the present and the past. To do this I set up three narrative lines.

In my notes, I call the first narrative the Baby Book. It deals with long-term memory from my first awareness through the early 1970s.

A second narrative intersects the first, relating stories of humiliation and loss. It contains rough details of my tangle with Alzheimer's. This narrative represents a mind-clogged, uncertain present. It is filled with memory lapses and language dificulties and the sudden barks of disappointment and loss.

A third stream is filled with recent Alzheimer's research. All this is mixed together, as it is in the brain, and follows a pattern of its own.

Memory is hunger.

ERNEST HEMINGWAY IN A MOVEABLE FEAST

I am going to tell the story of my life in an alphabet of ashes.

- BLAS DE OTERO IN TWENTY POEMS

Tl HAT JANUARY, MY FIFTY-SEVENTH BIRTHDAY, waS pleasant and eventful and I began to adjust to middle age. I no longer noticed how small facial lines became wrinkles. I was active and happy. My son Francesco, home from California, joined Joyce and me in the family herb-growing business in Virginia. I was equipped with a thin body free of aches and pains. I looked forward to a life to rival my Midwestern grandmother's 104 years. I was buoyant and displayed, occasionally, the unbecoming arrogance of youth.

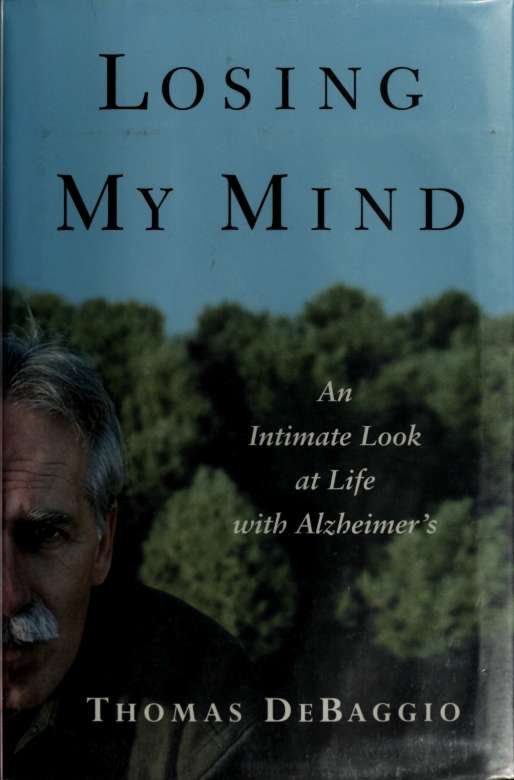

Then came a beautiful spring day later that year. It was the day after the tests were finished and the results reviewed. It was the day I was diagnosed with Alzheimer's. What time had hidden was now revealed. Genetic secrets, locked inside before my birth, were now in the open. I became a new member in the parade of horror created by Alzheimer's.

At first I viewed the diagnosis as a death sentence. Tears welled up in my eyes uncontrollably; spasms of depression grabbed me by the throat. I was nearer to death than I anticipated. A few days later I realized good might come of this. After forty years of pussyfooting with words, I finally had a story of hell to teU.

^-.

My parents grew up in an orderly, gende time, or so they remembered it. Their epoch was also full of dirty secrets, enslavement.

THOMAS DeBAGGIO

lynching, and two murderous convulsive world wars. It was a time to need luck. They escaped the influenza epidemic of 1918 and made it through the Great Depression of the thirties when food and jobs were scarce. Luck was with them in small Iowa towns named Eldora and Colfax.

Instead of focusing on the explosive reality of their time, they created a happier personal interval of their own imagining. This in turn created a great optimism in me and a gentle narrative of childhood tranquility. Soon I was scared and uplifted, as were they, by the time of my time, a world of conflagration, disorder, hope, ugliness, great beauty, and unnecessary death. Yet the imaginative world of kindness and promise they passed to me always remained untouched by the ugliness of congested cities, immoral wars, and encompassing greed.

Here I am at the moment of truth and all I can muster are hot screams and scribbled graffiti torn from my soul. Moments of slithering memory now define my life.

After a short, mild winter, a vivid spring settled around us. The weather was tame and herbs filled a sunny patch next to the greenhouse. They were strong and vigorous now, especially the rosemaries, the thymes, the lavenders. Their scents perfumed the air when I brushed by them.

The sun warmed the earth steadily and it was possible to spade and plant a kitchen garden with early seed crops of succulent lettuce to sweeten and color our meals. It was a spring in which you could be happy and a little carefree. There was much the earth had to say and you could hear it if you stayed quiet and listened intently.

There was something else that spring and it was unnamable. As with all unknowns, it was unsetding and had nothing to do with the weather. It was not something that gentle rains, bright sunny days, and an optimistic outlook would cure. It was an anonymous presence, yet I could feel its uneasy cadence. My memory, which had